Country Wine Cornucopia

Country wines. The name evokes a cottage in a peaceful countryside, set amid fields of lush vegetation, with birds and bees blissfully coasting on the late-summer breeze. Imagine hearing someone in the distance humming contentedly. (Music lovers can imagine the Peer Gynt Suite by Edvard Grieg.) The scene slowly comes into focus as someone with a broad smile carefully bottles and corks a special elixir. Surely it must be a wine made from the bounty of the land.

In the wine world, if you ask a viticulturist to define the word “fruit,” he or she would probably tell you it is “the grape.” The origin of the word “wine” is from the Latin word “vinum,” or vineyard. So a strict definition of wine is the fermented beverage made from grapes. But over the years the definition has been extended to include the juices of fruits and berries.

“Country wines” is the informal term that has been used for years to define fermented beverages made from the juices of fruits, vegetables or flowers. The broadest definition of wine could also include the fermentation of sugar solutions flavored with various flowers or herbs. Wine made with honey is called mead; wine from apples is cider (5 to 7% alcohol); and pear wine is known as perry.

Grapes can ferment without human intervention because they carry indigenous yeast and contain sufficient levels of sugar and nutrients. But the wise winemaker makes choices to produce a finer wine. He will use a commercial yeast strain, and he may dilute the must or add sugar, acid, nutrients or oak. Country wines, on the other hand, rarely have enough natural sugars and nutrients to ferment to the minimum alcoholic content of at least 7%. Wines made from fruits such as berries, peaches, pears, apples, rhubarb, tomatoes, watermelon, rosehip and dandelion benefit from the winemaker’s decision to control the acids, sugars, nutrients, vitamins and tannin content, as well as the yeast strain, to maximize the fruit flavors.

As a general rule of thumb, country wines have a limited shelf life while most grape wines benefit from at least a bit of aging. Country wines are, in computer terms, “WYSIWYG,” which stands for “what you see is what you get.” They are consumed while young, within three months to two years (with a few exceptions, like elderberry). Country wines generally do not improve with bottle age. The fruit flavors lose their freshness and the color fades. To maximize enjoyment from each of these wines, make sure you test and adjust the acidity and free sulfite levels before bottling.

What acid levels are you checking for and why? Most berries are high in acids. The easiest way to control the acids in berries and fruits for winemaking is amelioration (adding water) or limiting the quantity of berries or fruit to the volume of water used per gallon. This is the balancing act for the winemaker. While you want plenty of flavor, you do not want so much tartness that you pucker when you sip! Since acid is the backbone of a wine, titrate the acidity of the must (juice) before fermentation and, again, in the wine before bottling.

The acid range for dry fruit wines will be 0.55 to 0.65 percent. This is, of course, a generalization since there are many memorable fruit wines with acid levels of 0.70 to 0.80 percent. These wines are usually sweetened before bottling to balance the taste of higher acids.

Remember: If the must (juice) does not have enough acidity during fermentation it can be too slow or may stop fermenting. The resulting wine may also have a medicinal taste.

If higher acid levels are desired, consider balancing the acids with sugar after fermentation.

Other country wines — such as banana, dandelion, mead, melon, watermelon, persimmon, pear and tomato — need acid additions to make a wine balanced. The use of a commercial acid blend provides a balance of acids to make a pleasant wine. Old-fashioned recipes used oranges and lemons to provide citric acid. These recipes may still be used as long as the citrus peel is not added. The oils in the rinds can actually inhibit a healthy fermentation. The use of a complete yeast nutrient is strongly suggested in all country wines since these fruits and flowers lack sufficient nitrogen, trace minerals and vitamins that are essential for healthy yeast metabolic activity.

All fruits can vary in juice content. Geographical and weather conditions may also contribute to the overall liquid content of the fruit. Fruits benefit from the use of pectic enzymes to release the juice from the fruit before and during pressing. These enzymes need 1–4 hours or overnight contact to break down the pectin in the fruit. Treated juices settle better and filter more easily than untreated juices. Use fresh pectic enzymes and mark the label with a date as it loses strength during storage. In addition to the regular pectic enzymes there are two newer products for fruits. Pearex Adex is a pectic enzyme formulated for pears, apples and quince and other light colored fruits. Adex-G2 may be used for acidic dark fruits such as raspberries, blackberries, currants, blueberries and native American grapes, such as Concord. Follow recommended dosage for fruits.

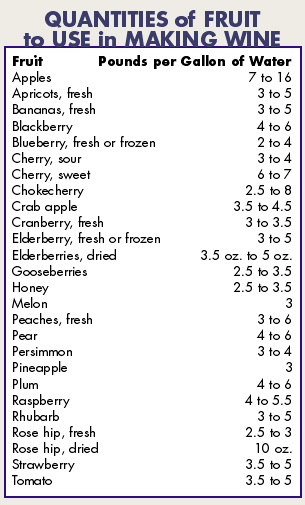

How much fruit does it take to make a gallon of wine? For guidelines, see the table at lower left. You can use more or less fruit than the recommended quantities. However, less fruit usually means less flavorful wine. More fruit per gallon of water will, in most cases, increase acidity and may make the wine too tart to be pleasurable.

Test the acidity of the must, using an acid test kit. Be sure to follow the guidelines for fruit wines. If using an acid test kit seems intimidating to you, ask your wine hobby supply store for help. They can show you how to do the test. Remember, the hydrometer and acid test kit are to the winemaker as a compass is to a mariner. They show winemakers where they have been and where they are going.

Every home winemaker should make room in his or her cellar for country wines. They taste fresh and fruity; they reflect the aroma and flavor of ripe fruit. They are inexpensive to make. They are refreshing to drink when the acids are balanced with the other wine components (alcohol, tannin and residual sugars). While most of your grape wines age, country wines can be the “drink now” beverages in your cellar. Country wines can be made in a dry, semi-dry, semi-sweet or sweet styles. A variety of fruits can be fermented separately and blended to make lively libations. There is something to be made for everyone’s palate!

Skill is required to make a good fruit wine. The three cardinal rules for working with fruits are the same as for grapes.

1. Always use ripe, unblemished fruit. You cannot make an excellent wine if you do not start with excellent fruit.

2. Always be clean! Sanitize all equipment before and after use.

3. Always use sulfites to stabilize the fruit and wine to prevent bacterial activity as well as oxidation.

Juice versus Pulp

Preparing the fruit for fermentation is important. Some fruits are soft and are easily mashed or crushed to produce juice. Hard fruits, like apples and pears, need to be cut and pressed to release their juice. Firm berries, like dried elderberries, can be softened by adding boiling water. Freezing berry fruits can release more juice. Stone fruits such as peaches, plums and apricots are fermented on the pulp and benefit from the use of pectic enzyme. Dried fruits can be minced and then treated with warm water to release the sugars and flavors. Citrus fruits, like oranges and lemons, use only the juice; the peels are never used because the oils are bitter tasting and can inhibit fermentation. Rhubarb is cut and sugared to release the juices. Flower wines should be made with only the petals; no stems, no greens.

The chart on the next page can be used as an easy guide to prepare your fruit. (Note: Some fruits can be prepared by more than one method.) Work with the fruit as soon as it is picked or purchased to ensure a quality wine. Remember, superior wines are made using superior quality fruit!

Reasons to Blend Fruit Wines

1. To Achieve Acid Balance. Most fruit wines are best enjoyed when acid levels are 0.55–0.65 percent total acidity. Berries and fruits often contain high levels of acid (mainly citric and malic). If the winemaker does not ameliorate the juice and lower the acid level, the wine will be too tart. Combining a high-acid fruit wine with a low-acid wine can maximize the flavors and bring the wine into balance.

2. To Maintain or Add Color. Black cherry and strawberry wines are notorious for pigment loss. Cherry, pear, and some varieties of plum wines tend to brown easily. Blending different wines, concentrated fruit juices or red wine coloring can enhance the visual enjoyment of the wine.

3. To add Complexity. Some fruits naturally taste good together. Think of the summer fruit bowl on the picnic table. Melons and apples have complementary flavors, as do pears and apples or pears, apricots and peaches. Berries and cherries have a rich taste when combined.

4. To Stretch the Crop Size. Sometimes we just do not have enough of one kind of fruit to make a batch of wine. Maybe the crop is small or the market is short of high quality fruit. By combining several types of fruits a gallon or two of great wine can be made.

Tips and Techniques

• Use ripe fruit. Cut and discard any bruised fruit.

• Remove pits or seeds. Obviously, this does not apply to strawberries, raspberries or other tiny-seeded berries (what a nightmare!).

• Use a pectic enzyme to increase juice yield and clarify the wine.

• Use a complete yeast nutrient to ensure a healthy fermentation.

• Use a yeast energizer if it is not included in the yeast nutrient.

• Use a straining bag to contain the fruit pulp and seeds during fermentation. It makes pressing easier and clean-up a breeze!

• Consider making a yeast starter to inoculate the must with a large, healthy yeast colony.

• Ferment at cooler temperatures (65 °F/18 °C) to keep the aromas in the wine.

• Monitor the fruit fermentation. Extended time on the seeds and pulp may cause excessive bitterness or astringency. The average macer- ation time is 2–3 days (for most berries); a maximum contact time of 6 days (cherries); or longer (elderberries).

• Consider holding back some of the sweetened unfermented juice to make a süssereserve, a sweet reserve that is added later to the stabilized wine. This technique imparts a vibrant fruity aroma and flavor to ordinary fruit wines. See your local hobby supply store for instructions on this technique. Fruit concentrates or natural fruit flavor- ing can also be used to boost flavor.

• Target alcohol production to no more than 11.5% unless you are planning to make a port-style wine. Country wines taste too hot when the alcohol level is too high. Remember, a lot of sugar is needed to balance a high-alcohol wine.

• Press lightly to avoid cracking seeds.

• Gently press, using rice hulls or food-grade cellulose, to get more juice from the fruit. For fruits, use 3 or 4 times the amount used for grapes. For grapes, mix 1 lb. rice hulls with every 100 lbs. grapes. For fruits, gently mix 1 lb. rice hulls with every 25–33 lbs. fruit. Or press with winery-grade cellulose, a new product. For grapes distribute 1 lb. cellulose in 150 lbs. grapes before pressing. For fruits, sprinkle 1/8 lb. cellulose in 38 lbs. fruit.

• Taste the juice while you are pressing. When you taste bitterness, stop!

• Dried fruits such as apricots, cran- berries or raisins in wine recipes deserve a special note. Since dried fruits are often preserved with sulfite, check the label. Remember to eliminate the Campden tablet used before fermentation. Wait for 24 hours before adding the yeast because sulfite will be in the must once the raisins soak. When fermentation is complete, add a Campden tablet.

• Cranberries contain a lot of fumaric acid, a yeast inhibitor. If your must does not start to ferment within a reasonable amount of time, you may ameliorate the must to dilute the fumaric acid.

• Cherries and peaches should be pitted. Although some recipes sug- gest cracking and adding a few of the pits to the must, I do not recommend this practice. The pits impart too much bitterness and an almond flavor.

• Ferment at a cooler temperature (65 °F or 18 °C) to maintain the aromas and flavors and to inhibit malolactic fermentation. You might also select a yeast strain that does not favor MLF, such as Lalvin EC- 1118 or Red Star Premier Cuvée.

• Use low-foaming yeasts or yeasts that work well at cooler temperatures. Examples: Red Star Côte des Blancs, Premier Cuvée or Pasteur Champagne; or Lalvin K1V-1116 or EC-1118. Winemakers producing a lot of fruit wines might wish to try the 500-gram package of Fermiblanc for enhanced aromatic expression or the Lalvin R2 which has excellent cold temperature tolerance and helps contribute fruit esters to the aroma profile.

• For higher-acid wines such as elderberry and blueberry, use Lalvin 71B-1122 yeast. It will help to metabolize some of the malic acid (usually 15%-20%), thereby reducing some of the acidity in the finished wine.

• Try a “red wine yeast” for elder- berries, blueberries or plums. Experiment with the Red Star Pasteur Red, Lalvin RC-212 or Fermirouge yeasts.

• Inhibit malolactic fermentation (MLF). The major acids contained in most country wines are citric and malic acid. Cool fermentations and the judicious use of sulfites will help prevent MLF.

• Consider blending to balance acidity. Blend high acid fruit wines with low acid fruit wines. Example: High-acid blueberry wine with low-acid Rome, Delicious or McIntosh wine.

• Rack the wine from the lees (sediment) within a week or two after fermentation is complete (– 1.5 °Brix, 0.992 specific gravity).

• Fine the wine with bentonite (fruits resulting in white wines), Sparkolloid® (wines with color) or Kieselsol (white or colored wines) according to package directions.

Make a Yeast Starter

Because most berries, pitted fruits and rhubarb spoil easily, it is important to ferment the fruit at peak ripeness. A large, healthy yeast culture can ferment the fruit effectively since it is an expanded colony, having multiplied sufficiently before being introduced to the must. This large yeast culture can be prepared with a yeast starter.

To make a starter, bring to boil 1 cup orange juice and 2 tablespoons sugar. Let solution cool to 70–80 °F (21–27 °C). Stir in 1/2 teaspoon complete yeast nutrient. To rehydrate yeast, measure 1/4 cup warm water at 100–105 °F (37–40 °C), then sprinkle yeast on top. Let yeast sit for 5 to 10 minutes. Stir to dissolve. Add to orange juice solution. Sanitize a 750-ml wine bottle or pint-size jar. Pour orange juice and yeast solution into clean bottle. Cover with a clean cloth or fit bottle with an airlock and #2 drilled rubber stopper. Yeast starter will be ready in 12 to 24 hours.

Country Wine Recipes

Apple Wine and Cider

More than100 types of apples are available and can be used to make apple wine. Try combining varieties for more complex apple taste. Low- and high-acid varieties can be crushed together with excellent results.

Sparkling Apple Cider

Makes 1 gallon (3.8 liters)

Ingredients:

1 gallon (3.8 liters) of fresh apple cider without preservatives (sodium benzoate or sulfites)

10 drops liquid pectic enzyme (if using dry pectic enzyme, follow manufacturer’s directions)

1 teaspoon yeast nutrient, dissolved in 1 tablespoon of water

1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved in warm water

1 packet of wine yeast (Red Star Pasteur Champagne, Premier Cuvée or Côte des Blancs; Lalvin K1-V1116 or EC-1118)

1/4 cup corn sugar dissolved in 1/4 cup water

Step-by-step:

Stir the apple cider, pectic enzyme, yeast nutrient and dissolved Campden tablet together in your primary fermenter. The tablet will help to prevent browning and the pectic enzyme will aid in clearing. Cover.

After 24 hours, rehydrate wine yeast in 1/4 cup warm water (105 °F, 41 °C) for 15 minutes. Stir thoroughly into the must (cider). Cover.

Stir twice daily. After 4 to 6 days, siphon cider into a glass secondary fermenter (8 °Brix, specific gravity on the hydrometer will be 1.030 or lower). Attach an airlock filled with approximately one ounce of water. Note: A cider has no additional sugar added for fermentation. Hence, it is a low-alcohol beverage.

In 2 to 4 weeks, the fermentation will be complete (0 to -1.5 °Brix, specific gravity will be 1.000 or lower). Rack the hard cider into another clean, sanitized glass secondary, leaving the undisturbed sediment on the bottom of the fermenter. Discard the sediment.

Stir the 1/4 cup dissolved corn sugar into the cider. Cider may be bottled in sanitized champagne or homebrew bottles. Apply crown caps. (Note: Because you added sugar and the cider contains residual yeast, a second fermentation will occur in the bottle to carbonate the beverage. Be sure to use the recommended bottles, which are made to withstand the pressure of fermentation.)

Age for 3 months. Chill. Since a small skim of yeast rests on the bottom of these bottles, try not to disturb the sediment while pouring. Tilt the glass at a 45° angle and gently tilt bottle as you pour.

Strawberry Wine

Strawberry wine colors range from deep red to light pink to pinkish-orange. However, the color tends to be unstable. For a more deeply colored wine, choose strawberries that are red all the way through.To enhance the color and flavor of fermented strawberry wine, try adding a strawberry concentrate or strawberry juice. When adding a concentrate or juice to a finished wine, remember to add potassium sorbate (1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon per gallon) to prevent further fermentation.

Strawberry Wine

Makes 1 gallon (3.8 liters)

Ingredients:

3–5 pounds (1.4 to 2.25 kg) fully ripened or frozen strawberries

7 pints water

2 pounds (0.9 kg) corn sugar

1 to 1-1/2 teaspoons acid blend

1/4 teaspoon grape tannin, dissolved in a small amount of boiling water

10 drops liquid pectic enzyme (if using dry pectic enzyme, follow manufacturer’s directions)

1 teaspoon yeast nutrient with energizer

1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved

1 package wine yeast (Red Star Côte des Blancs or Lalvin 71B-1122)

Fine mesh straining bag

After fermentation:

1 Campden tablet

Sparkolloid, per package instructions

Potassium sorbate, if wine is to be sweet

Step-by-step:

Pick berries fully ripe. Remove stems, leaves and foreign matter. Cut and discard any rotten fruit. Wash and drain. To contain pulp and tiny seeds, place fruit in a fine-mesh nylon straining bag. To keep all of the pulp in the straining bag, tie the top of the bag. If frozen fruit is used, thaw. Lightly mash the fresh fruit. Place juice into primary fermenter. Place the fruit-filled bag in the primary fermenter.

Combine water and sugar in a saucepot and heat to dissolve the sugar. Cool. Pour the sugar solution into primary fermenter. Stir in acid blend, grape tannin, pectic enzyme, yeast nutrient and Campden tablet, per instructions above. Hydrometer reading will be 21–22 °Brix. Take an acid reading using an acid test kit. Adjust acid levels to 0.55 to 0.65 (1 teaspoon acid blend will increase the acid level by approximately 0.15). If desired, prepare a yeast starter at this time. Cover primary fermenter and wait 24 hours.

Add the yeast starter or rehydrate the package of wine yeast in 1/4 cup warm (105 °F, 41 °C) water per package instructions. Stir the yeast into the must. Cover. Stir vigorously twice daily. After 4 to 6 days or when hydrometer reading is 8 °Brix (specific gravity 1.030), press juice from bag and place wine into glass secondary fermenter. Attach airlock half-filled with water (1 ounce).

When fermentation is complete (0 to 1.5 °Brix, specific gravity 1.000 to 0.994), about 7 to 10 days, rack off the sediment into another clean and sterile glass secondary. Stabilize by adding 1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved in a small amount of warm water.

Once fermentation is complete, it will begin to clear. Add the fining (clearing) agent, Sparkolloid, according to directions on package. Let sit 2–3 weeks and rack again. Let sit 3 more weeks and rack again. When clear, taste and then test the acidity using an acid test kit. If the acid level needs adjusting, add citric acid. Filter and bottle.

If a dry wine is preferred, check the sulfite level and adjust to 35–45 ppm free sulfite. For a sweet wine, dissolve 1/2 teaspoon potassium sorbate per gallon (3.8 liters) in a small amount of water. Add to the wine and stir. Then dissolve 4 tablespoons sugar in 2 tablespoons water (the residual sugar level will be a dry level with this amount). Add to the wine. Stir thoroughly. Wait approximately 20–30 minutes before tasting the wine. Add more sugar using a simple syrup solution, as desired. Filter if needed. Bottle the wine.

Rhubarb Wine

Rhubarb is a delicate wine with a floral nose. It is consumed within a year or two, after which the aromas and flavor will not be as fresh. Consider blending apple cider or strawberry wine to rhubarb wine for a more complex taste.

Rhubarb Wine

Makes 1 gallon (3.8 liters)

Ingredients:

3 pounds (1.35 kg) rhubarb, thinly sliced but not peeled

2-1/4 pounds (1 kg) corn sugar

1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved

2 teaspoons calcium carbonate

1 teaspoon complete nutrient

2 teaspoons acid blend

1–4 ounces (28–112 g) white grape concentrate (optional)

1 package wine yeast

After fermentation:

1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved

1/2 teaspoon potassium sorbate

12 ounces (336 g) sugar dissolved in 1/2 cup warm water

Step-by-step:

Wash and drain ripe rhubarb stalks. Do not use the leafy part of the plant. Cut stalks into thin slices. Stir the slices together with the dry sugar. Cover until most of the sugar has dissolved, about 24 hours. Strain off the liquid. (Save the liquid, of course!) Stir the pulp in a little water. Strain again. With a little more water, rinse all of the remaining sugar and place it with the rhubarb liquor in a primary fermenter. Use enough water to make up volume to 1-1/8 gallons (4.3 kg). Stir thoroughly to dissolve all of the sugar. Discard the pulp.

In a 2-cup measuring container, remove 1 cup of the rhubarb liquor and stir in the calcium carbonate. Foaming will occur but will subside. (Note: The calcium carbonate neutralizes the excess oxalic acid that is present in the rhubarb.) When all foaming ceases, stir the calcium carbonate mixture into the rhubarb liquor.

Stir in the yeast nutrient, acid blend, grape concentrate, and dissolved Campden. Cover and let sit for 24 hours. Measure 1/4 cup of warm (105 °F, 41 °C) water to rehydate the yeast. Sprinkle yeast in the water and let sit for at least 5 minutes. Stir to dissolve. Stir yeast into the must. Cover. Stir vigorously twice daily. After 3 to 4 days or when the hydrometer reading is 8 °Brix, specific gravity 1.030, siphon wine into a glass secondary fermenter. Attach an airlock half-filled with water (1 ounce).

When ferment is complete (0 to -1.5 °Brix, specific gravity 1.000 to 0.994), about 1-2 weeks, rack off the sediment into another clean and sterile glass secondary. Stabilize by adding 1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved in a small amount of warm water.

Once fermentation is complete, it will begin to clear. Add the fining (clearing) agent, Sparkolloid, according to directions on package. Let sit 2-3 weeks and rack again. After 3 more weeks rack again. If a dry wine is preferred, check the sulfite level and adjust to 35-45 ppm free sulfite.

For a sweet wine, dissolve 1/2 teaspoon potassium sorbate in a small amount of water. Add to the wine and stir. Then dissolve sugar in 2 tablespoons warm water. Add to the wine. Stir thoroughly. Wait 20 to 30 minutes to taste and evaluate the sweetness. If additional sweetness is desired, further sugar additions may be made.

Filter wine, if desired. Siphon wine into clean, sanitized bottles and cork. Allow wine to rest upright for 10 days before placing bottles on their sides.

Rose Hip Wine

If Ethel Merman had ever tasted rose-hip wine, the lyrics of her most famous song might have been a bit different. (“Everything’s coming up rose hips?”) If you have rose bushes you can use the rose hips (the base of the flower that bulges after the petals have fallen) as long as you do not spray with pesticides. A delicate floral wine is produced. White grape concentrate will give additional body and flavor. Sweeten prior to bottling to achieve a semi-dry to sweet residual sugar level (4 to 24 tablespoons of sugar per gallon). Rose hips are high in Vitamin C.

Rose Hip Wine

Makes 1 gallon (3.8 liters)

Ingredients:

2-1/2 pounds (1.1 kg) fresh rose hips or 10 oz. dried whole rose hips

7-1/2 pints hot water

2 pounds (0.9 kg) sugar

4–6 ounces (112–168 g) white grape concentrate

1 teaspoon acid blend

1 teaspoon complete yeast nutrient

1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved in a bit of hot water

1 package yeast (Lalvin K1-V1116 or Red Star Champagne)

After fermentation:

1 Campden tablet

Bentonite, per package instructions

Potassium sorbate

Step-by-step:

Sort rose hips, discard foreign matter and stems. Wash, drain and crush rose hips. Place in a fine mesh straining bag; tie the top. Place sugar, grape concentrate, acid blend, yeast nutrient and dissolved Campden in the fermenter.

Pour the hot water over ingredients. Stir until sugar is dissolved. Add rose hips. Cover with clean cloth, fermenter lid or plastic cover. Wait 24 hours. Test for acidity; adjust. Rehydrate the yeast in 1/4 cup warm water. Sprinkle the yeast on top. Wait 5 minutes; stir to mix thoroughly. Add yeast to rose hip must. Stir thoroughly. Cover. Stir twice a day.

Press the pulp lightly when hydrometer reading is 8 °Brix or specific gravity is 1.030 (3 to 4 days). Siphon wine into a clean, sanitized secondary fermenter and attach a drilled rubber stopper and air lock filled with 1 ounce water. Allow wine to ferment to -1.5 °Brix or specific gravity 0.994. Add 1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved in 1/4 cup of warm water. Add bentonite according to manufacturer’s directions. Wait 2-3 weeks, siphon wine away from sediment. After 4-6 week intervals, siphon a second and third time. Filter wine.

Taste the wine to determine if sweetening is desired. If sugar is added, 1/2 teaspoon potassium sorbate is added per gallon (3.8 liters) of wine. To sweeten the wine, start with 4–8 ounces (112–224 g) sugar in 1/4 cup warm water, stirring to dissolve. Add to the wine and stir thoroughly. Wait 20 to 30 minutes before tasting. Add additional sugar, to taste, until desired sweetness is achieved. Filter, if desired. Bottle.