Turning 21 and ordering your first glass of wine is always a thrill, but turning 21 during the first lockdown of a global pandemic makes that quite challenging.

During the initial COVID-19 lockdown, I read William Baker’s autobiography, in which he recounts his time as an Alcatraz prisoner. What stood out to me most was his experience making wine with stolen fruit and bread yeast. I thought to myself, “If he can do this in prison, I can do it in quarantine.” Thankfully I was turning 21 in a few days, so I asked my parents for a 5-gallon (19-L) bucket and some apple juice.

Immediately I was captivated by the process of carefully measuring ingredients and seeing how they interact even though I was completely unaware of each ingredients’ purpose. I tend to jump into new things because I love the thrill of having to figure things out on my own through trial and error. I was just trusting a recipe I found online, but the more I read about winemaking, the more I wanted to learn. Soon I was boring my family at the dinner table explaining why I had bought an acid blend for my next batch.

I had yet to think about what to do once it was time to bottle, so after 7 weeks, I had to get creative. Using recycled Chickfila gallon jugs and mason jars, I stored the wine in my parent’s kitchen. This may have been okay if it was temporary, but my school, Berry College, reopened, so I moved back to my dry campus and had to leave all of my new wine with my family (who rarely consume alcohol).

Months later, when my second, third, and fourth batches were ready to bottle, my parents told me it was time to find a new home for my rapidly growing collection of wines. Without any thought, I made an Instagram, branded my new hobby as “Watkinsville Wine” (named for my hometown), and started sharing my wine with all of my friends and family. As long as I am not selling it, it’s legal, right?

In most places that answer would be yes. Unfortunately, Watkinsville is a dry city and the surrounding county is also dry, which means I should not be freely sharing alcohol with anyone outside of my nuclear family. My mom, the one who broke the news to me, gave me an ultimatum; I could either stop making wine or I could get licensed. To me, getting licensed seemed like the easiest option. How hard could it be?

Apparently it’s very hard when you live in a dry county.

Because I was making an alcoholic beverage, I was required to find a production site in the county’s industrial zone, which is very small and on the opposite side of the county from where my parents’ live. Without a production site I couldn’t submit my federal application. Even if a space in Oconee County’s industrial zone became available, I couldn’t afford rent being a full-time student making minimum wage. And even if I could afford it, the production site would only allow me to make the wine, not actually sell it. To sell wine in my city, or surrounding county, I would need to make most of my profit from non-alcoholic products. As a winemaker, 100% of my products were going to be alcoholic, so this posed a serious issue. Without selling wine, there would be no source of income to pay for the expensive rent in the industrial zone.

I spent months researching and talking with local government officials, hoping to learn something that would help me in my endeavors. I was totally lost; I had never heard of zoning laws before and, to be honest, I didn’t even know what the word municipality meant. Thankfully, each city council member, zoning officer, and county commissioner was encouraging as we collaborated. They were very open to adding a winery ordinance, but the lack of precedent made it a complex and slow process.

As part of my research, I visited wineries in North Georgia to gain insight on starting a winery and to taste some delicious wines. I learned the most from the owner of Sweet Acre Farms, who started his farm winery in a dry county years prior. According to Georgia state law, a farm winery does not require local licensing and a winemaker can acquire all the licensing necessary to produce, sell, and distribute fruit wine, as long as a percentage of the fruits are locally sourced. This meant I could choose a production site in any zone. Just to be sure, I fact checked it with my attorney dad and sent it to my Georgia Department of Revenue representative, both of whom confirmed my interpretation of state code.

I do not want to rely on Watkinsville Wine to pay my bills because it would become a job, losing its spark and artistic element that I fell in love with.

Now the only other obstacle for starting Watkinsville Wine was the fact that you have to be age 25 to open a winery per the Georgia Code and I was only 22 at the time. Again, I relied on the support and loving help of people around me. My mom, who has been supportive from day one, agreed to be my LLC partner, so that I could register Watkinsville Wine LLC with the Secretary of State and the Georgia Department of Revenue.

During this time, I had my first round of interviews for my current full-time job. The CEO, Jeff Jahn, was immediately interested in my endeavor since he started his company, DynamiX, while he was a student at Berry College years prior. He told me about the school’s entrepreneurship program and suggested I connect with Paula Englis, who directed the funding of entrepreneurial projects on campus. With her guidance, I entered a three-round, Shark Tank-like competition on campus for young entrepreneurs.

Because Berry College is a dry campus, I was not allowed to bring my product to the competition, so I filled my labeled wine bottles with water and purple food coloring to showcase a theoretical final product. Three rounds of competition later and I won the first place prize of $6,000 for Watkinsville Wine. This, and another $2,500 that I won from another pitch competition on campus, was enough to pay for startup costs, including better equipment, tax bonding, and a winemaking seminar in Atlanta to learn more about fruit wine. Knowing about the Georgia Farm Winery ordinance allowed me to submit my federal application with my parent’s farm as a production site, despite it not being an industrial zone.

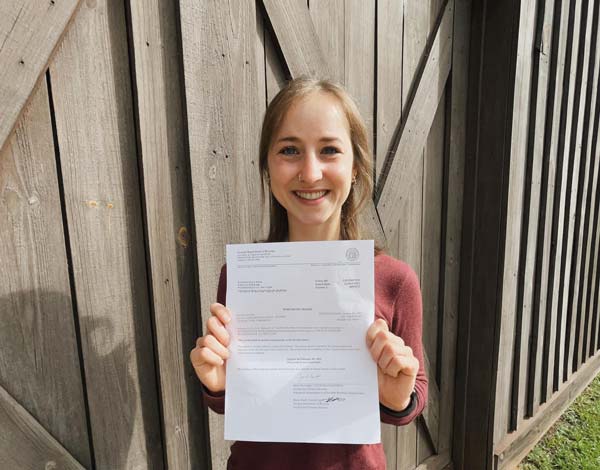

From here, it was a matter of getting my federal and state applications approved, passing the state inspection, and submitting a letter of intent to my county’s Board of Commissioners. According to Georgia law, they had 60 days to draft and enact a law prohibiting Watkinsville Wine from opening if they opposed my business plan. Instead of resisting my farm winery, the Board opted to amend the zoning ordinance definition of “Agrotourism” to include Farm Wineries licensed under Georgia Law, which meant my production site complied with the local zoning code.

With a federal permit, state license, and a growing presence on social media, Watkinsville Wine was born in December 2021, six months after graduating college. Only after the fact did I realize that I needed some sort of accounting and bookkeeping solution, so the day I got my state license, I taught myself how to use Quickbooks. Within the first few days, I delivered my first legal bottle of wine as a legitimate business and recorded my first income.

Ever since I have been constantly learning and evolving the business to meet the needs of my customers, increase the quality of my products, and have fun. One example of how I have evolved is with the expansion of the product line. To reach a larger customer base and eliminate waste in the production process, my mom and I transform the leftover wine, after racking, into wine jams and jellies. These are especially fun to pair with cheeses and crackers when I host tasting parties or attend events as a vendor. Furthermore, it allows me to reach a younger consumer base and add variety to my product line.

Because making fruit wine is first and foremost an art and a passion, I am keeping it a very small business and do not take a paycheck. Every bit of profit circles back into the business so I can afford to keep learning and improving my product. I do not want to rely on Watkinsville Wine to pay my bills because it would become a job, losing its spark and artistic element that I fell in love with, so all profits just support winemaking endeavors. Furthermore, keeping the business small allows me to manage every aspect of operations, including marketing, winemaking, customer relations, delivery, and finances.

I love the freedom of creating a brand I am proud of and that allows me to interact personally with each and every person who supports Watkinsville Wine and connect with winemakers all over the country through this magazine and the annual WineMaker’s Conference. This was my first year attending and I had the most incredible experience, meeting kind, passionate, and talented home winemakers, vendors, and speakers. Not only did I walk away with a wealth of knowledge, but I left San Luis Obispo with new friends and contacts that I cannot wait to reconnect with again in Eugene, Oregon in 2023!