Balanced, Low-Alcohol Wines and Reducing Water Consumption

Q I’ve seen a few lower alcohol wines come onto the market lately and as my wife and I get older we aren’t such big fans of boozy wines, especially those over 15%. We’re trying to cut back a bit on alcohol in our lives in general, for calories’ sake, and are looking to keep enjoying our wine. Also, it seems that lately we’ve been experiencing more heatwaves in our growing area, making it harder and harder to keep our annual vintage of Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and Cabernet (we’re in California’s Mendocino County) under 14% alcohol where we’d like it. Do you have any tips for home winemakers who want to try to make balanced, tasty wines while still keeping alcohol moderate? I know it can’t be just as simple as picking the grapes a little greener.

Francis Holder

Hopland, California

A Funny you mention this topic because I’m currently working on a lower-alcohol project at work (at Plata Wine Partners, I often develop custom projects for clients, and this is one). The brief for me is to come up with a delicious, balanced Pinot Noir and rosé that clock in around 9% alcohol. There is some evidence that the typical U.S. consumer is increasingly interested in buying and enjoying wines with more moderate levels of alcohol.

Like you, they seem to be interested in a) avoiding getting a little too tipsy and/or b) achieving health and wellness goals of reducing alcohol consumption like curtailing inflammation or lowering calorie consumption. Now, of course, for my project I’m going to have to use reverse osmosis machinery to physically remove some of the alcohol, something that your usual home winemaker won’t be dealing with. The process can cost thousands of dollars to employ and only larger-scale bottling runs can justify it. That being said there are many things that winemakers can employ to try to get balanced, delicious wines with naturally lower alcohol levels.

Whatever a winemaker’s goal, we all have to think about how alcohol plays (or doesn’t play) well with the other components in any given wine. Alcohol never stands alone and, contrary to what some wine advocacy groups would have us believe, isn’t the only component important for “balance.” Total acidity, pH, aromatic complexity, tannin, sugar, and carbon dioxide levels, especially, are all important pieces of the overall picture of a wine.

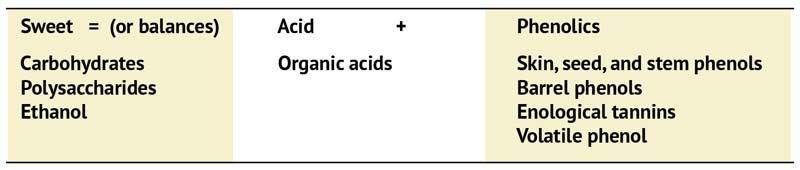

Bruce W. Zoecklein at Virginia Tech sketches out the below schematic, which explains the interactions:

Alcohol brings a sense of body to wine and can also increase the perception of tannin. Sugar can mask both acidity and tannin and also can give the impression of body and a “full” mouthfeel. It often is present in lower-alcohol wine because of these effects. In order to not have a product be too sweet, higher acid is often required to balance the sugar if present. Acid and phenolics reinforce and amplify each other so too much of one can bring out a negative in another. The most important thing to remember is that if alcohol is going to be lower, other “sweet” components have to be higher or something on the other side of the equation (acid + phenolics) has to be lower.

Crafting lower-alcohol wine means needing to recalculate its balance point. It can be tricky to do at home but is certainly an attainable goal. Photo by Charlie A. Parker/Images Plus

Carbon dioxide bubbles will contribute body, which is one of the reasons many sparkling wines can be so successful at lower alcohol levels. Floral, distinctive, or especially rich aromatic varietals as well, will help the “nose” take the place of some of the complexity that ripeness and alcohol might have contributed. For this reason, Chardonnay is hard to do on a low-alcohol level whereas Riesling can really shine.

Like I mention above, most winemakers aiming for lower-alcohol wines aren’t simply removing alcohol post-fermentation but are taking a systemic, holistic approach. Below are some techniques to employ if you are seeking to reduce the sugar levels in your grapes or the eventual alcohol levels in your wines.

Planning What to Make

- Plan to make varietals that don’t rely on the heft of booze for style and that bring other charms to the party. Floral and aromatic varietals like Riesling and Malvasia Bianca, for example, are lovely at lower alcohol levels. In your case, your Sauvignon Blanc may be a really great play. Instead of trying to make your Cabernet super “lite” maybe buy some Pinot Noir from a neighbor?

- Choose to make wine styles that naturally lend themselves to lower alcohol like low tannin, sparkling (or slightly spritzy . . . think vinho verde) products.

In the Vineyard

- Choose naturally lower-acid sites, especially those with hot nights (over 70 °F/21 °C) and lower diurnal fluctuation, which will burn off residual acid earlier in the season. Especially in whites, this will allow for full-flavored picking at lower Brix. I would think your Mendocino Sauvignon Blanc would be ideal for this.

- Hold off on irrigation as much as possible post-veraison. This pushes the vine into senescence and developing tannins earlier in the season.

- Don’t thin fruit too much. A higher tonnage per acre (contrary to popular belief) will assist to ripen fruit faster for a given leaf load.

- Remove laterals.

- Make sure you don’t have too much canopy, especially for reds. Dappled, open sunlight into the fruit zone is critical as it decreases malic acid during ripening. Also, you do not want bell pepper pyrazines in your Cabernet, so be especially careful here.

- Leaf pluck in the fruit zone, as long as a heat wave doesn’t threaten sunburn.

- Try box-pruning or “California sprawl” to get dappled sunlight into all of the vine.

- Get out in the vineyard and taste constantly as harvest approaches. Don’t be afraid to pick some “early lots” if you can in order to get some lower alcohol blenders. You may be surprised at the quality, especially if you’ve followed some of the above suggestions.

On the Crush Pad

- Add water generously to combat any berry dehydration. Water added early always integrates better.

- Adding untoasted oak dust/shavings at the crusher can help combat green flavors in red grapes.

In the Fermentation Vat

- Warmer fermentations (more suitable for reds than whites) can help “blow off” a certain amount of alcohol, perhaps 0.25–1%.

- Open top fermenters, like those often employed in producing Pinot Noir, can also contribute to ethanol “blow off” and reduce alcohol slightly by another 0.25–1%.

- For white wines that will not be 100% malic acid complete, choose a malic acid reducing yeast like Lalvin C. It gives a 30% reduction in malic acid during primary fermentation and “rounder” flavor without any undesired malolactic fermentation byproducts that may not be style appropriate.

- Try arresting fermentation, especially for whites that have higher acid, to leave a little residual sugar. This will result in a lower final alcohol and will balance out the higher acid/lower alcohol and lend some body to the finished wine that alcohol would’ve contributed.

In the Cellar

- Try blending lots from early-pick, warmer-night sites (see above, less acid) with those that come from higher-flavored, more “traditional” sites.

- Surprisingly, some of the newer tannin preparations from companies like Laffort, AEB, and Enartis can really smooth out rough phenolics and make “green” disappear in young and finished wines. I hear good things about the “Rouge” tannin from AEB and the “Dark Chocolate” tannin from Enartis. By removing green or rough-feeling tannins, the reduction of body-enhancing alcohol won’t be missed quite so much.

- If you are storing sweet wine, chill and/or filter in order to keep tabs on possible re-fermentation. Certainly sterile-filter the wine via crossflow or 0.45 micron nominal pad or cartridge if this is the case.

At Bottling

- I know you mentioned health as a goal, but don’t be afraid of adding 1–2 g/L residual sugar to achieve mouthfeel and flavor balance at bottling. I like to buy a little grape juice concentrate and meter it in maybe around 1–3 mL/L, just to give some roundness and add to the finish. Lower alcohol wines often need to be balanced in this way (sterile filter afterwards) and it can really help.

Q We live in a pretty dry area of eastern Washington state. I’ve got a nice little winery setup and make about 5–7 barrels of mixed reds a year, depending on how ambitious we feel. One thing I’ve noticed is our water bill has really gone up a lot — to a point where it’s a significant monetary investment in the process and I have to factor it into our overall winemaking budget. I know we’re in a drought-prone area and it might just get worse as the years go on. What tips do you have for how winemakers can save water during the entire process from start to finish?

Rita Hendrickson

Pasco, Washington

A It generally takes about 6 gal. (23 L) of water to make one gallon (3.8 L) of wine though estimates vary from as little as 2 gallons (7.6 L) all the way up to 20 gallons (76 L). Many folks have no idea where they fall on this spectrum and performing some kind of a water audit, even if it’s just to measure how much water you use to clean a typical small tank or barrel, will help establish a baseline.

Measuring your water consumption can start with installing flow meters to measure usage at key points like on the crush pad, at filtration, and at barrel washing areas. By filling up that stainless tub or drum you’ll get an idea how much wash-water gets used when you do any given task. Do the math to figure out how many gallons or liters of water per length of hose it takes to fill that volume. Use your current usage to create a realistic target for reduction.

At Harvest

- Pick “balanced” grapes, not overripe raisins, so you don’t have to add additional hydration water. Similarly, every time you avoid an addition (acid adjustment, etc.), you avoid having to clean and sanitize the tools.

- Cover your crush and reception area to minimize the “baking on” of waste material. The shade will make juice and grape skins easier to remove from equipment and will reduce the amount of water needed for cleaning.

- Pre-clean with brushes, brooms, and elbow grease before resorting to water for soaking and rinsing.

In the Cellar

- Move from an old-fashioned three-step cleaning (caustic cycle, acid-neutralization cycle, and then water rinse) to a two-step process (K-OH followed by per-acetic acid or “quats” followed by a water rinse). If you wait 30 minutes after the per-acetic acid cycle, you don’t need to rinse with water.

- Invest in a pressure washer. Pressure washers clean floors and equipment well while only using between 2–4 gallons (8–14 L) per minute. Bonus — they are fun to use! One of my favorite winery jobs is pressure washing because you can always see what you’ve accomplished.

- Use water hoses with automatic shut-off valves and timers where appropriate.

- Minimizing the length and diameter of hoses as appropriate will use less water in sanitation.

- Be efficient with tank and barrel movements. The more you rack or move wine from one vessel to the next, the more often you have to clean and sanitize gear . . . and the more water you will use.

- If you employ small variable “floating top” tanks for wine storage, you have to move wine less-often for breakdowns.

- Use “dirty” wash water as secondary wash water for other vessels (water recycling). Empty dirty water out into a sump and re-use for other tasks. Use relatively clean rinse water from your last phase of cleaning as the dirty first-step water for barrel cleaning.

- Clean carboys, kegs, and tanks in batches. Use the rinse water from one as the cleaning water for the next.

- Don’t chase wine with water in hoses if you can — flush/push with gas and a pig (winemaker slang for a foam ball that you push through the line).

Barrels

- About a third of all of the water a winery consumes can be in barrel washing! Be water-wise in this step.

- Coordinate barrel emptying and filling work to reduce the amount of time that barrels are empty. Freshly-emptied barrels don’t have to be swelled up with water again.

- Soak heads separately by flipping end-to-end.

- Use rinse water from one barrel to do initial cleaning of next (though do dump your cleaning water if you’ve got an infected barrel).

Be water-wise when you wash your barrels. About a third of all of the water a winery consumes can be in barrel washing!

Filtration and Bottling

- Filters take water to clean and set up. If your red wine has a pH under 3.75, its free SO2 was maintained, doesn’t have any volatile acidity climbing, and you’re going to bottle it dry . . . do you really need to filter it before bottling?

- Consider using a liquid cellulose gum, like Laffort’s Celstab®, for cold stability instead of the traditional chilling and seeding with potassium bitartrate crystals.

- Settling well before hand, perhaps using isinglass, may enable you to filter with one pass rather than twice.

Scrutinize the Lab (or Kitchen) Area

- Install aerators in all sinks so less water is used when sink taps are turned on.

- Foot-pedal operated “on/off” taps (like those often seen in hospitals) use less water when washing up at sinks.

- Under-sink or on-demand tankless water heaters get water up to temperature quickly, without having to travel a long distance from a traditional water heater tank. Luckily, depending on where you live, there may be significant government rebates or tax credits associated with switching over to these kinds of water heaters.

Change is tough

It might be hard to make reaching for the squeegee, instead of the hose. One little trick we winemaking homies (home-based winemakers) can adapt from the large wineries is the good old reward system. If you’ve got a group of buddies that works together when you’re making wine, or if it’s your kids and your spouse, try to have a “water jar” where you toss in a pebble or a colored ping pong ball when you see someone doing the right thing. Once the jar is full, the group gets to partake in a reward like a barbeque or an excursion out to your local wine country. Keep it fun!