Q

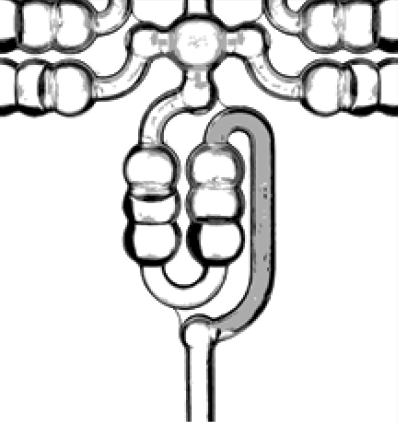

I was a fool and didn’t keep track of the water level in the airlocks of my 5-gallon (19-L) carboys as they were aging the past four years. I should not have had airlocks in the first place, I guess, and now there is a film on the wine surface. Is it ruined?

Mike Hennard

Caneadea, New York

A

It sounds to me like some “bad bugs” (ambient bacteria or yeast cells) got into your wine. After four years of aging, having a batch infected due to a bad airlock must be heartbreaking I’m sure. Depending on what the organisms are and how long the wine was exposed, it’s quite possible that the wine might be all right to drink. If the wine still tastes and smells fine, you could take a chance and bump the free SO2 levels up to around 35, do a sterile (0.45 micron nominal pore size) filtration to exclude what bad guys you can and take it to bottle. You’re looking for classic oxidative spoilage cues like aromas of nail polish, nail polish remover and vinegar. If you don’t sense any of these indicators of microbial spoilage, and don’t perceive any spritziness or dissolved carbon dioxide gas in the mouth, it’s always worth a “Hail Mary” salvage attempt at bottling. As “no human pathogen can survive in wine” (to quote one of my UC-Davis microbiology professors) because of wine’s alcohol level and naturally low pH, the wine will be perfectly safe to drink. However, even if it does smell and taste fine today, be aware that the wine may not age as well or as long since it has been prematurely exposed to a higher than desirable level of oxygen.

Since you describe a film on the surface of the wine, you are probably dealing with some kind of microaerophilic organism like the kinds of yeast encouraged to grow on some kinds of Sherry while aging. These yeast cells actually consume alcohol, metabolizing it into acetaldehyde, and in turn imparting some of the oxidized, nutty and toasty flavors we associate with this kind of specialist “flor Sherry.” However, depending on what kind of wine you made, especially if it comes from fruit other than grapes, these characteristics may not be welcome. If you do in fact like the effect the film has on your wine, you might want to try leaving one carboy intact, just as an experiment.

If the wine does show signs of objectionable aromas and flavors, then there is really not much you can do. Sometimes adding excess sulfur dioxide, like bumping the FSO2 up to around 45 ppm (maintain at 25-28 ppm FSO2 thereafter) can bind up aldehydes and reduce some of the objectionable smell. It will still be necessary to filter the wine as you obviously have microbial visitors that can still consume oxygen and spoil the wine in the bottle.

You are correct that you should’ve transferred the wine out of the carboys, and out from under the airlocks long ago. Typically we rack the wine from a fermentation-lock container down to a barrel, or at least to a carboy with a “hard bung” airtight closure, after all primary and secondary fermentations are complete. For most wines, this occurs between 2-4 months of age. Four years is also a long time to age a wine before bottling. Most top-scoring red wines made in the U.S. are bottled after 18–24 months in barrel. Whatever you do or whenever you bottle, please protect future batches by getting it down into barrel, or at least into completely topped carboys sealed with something more solid than a topper that depends on an evaporating seal of water to protect it.

Q

I have been making wine for about a year using kits and grapes. I currently use the method of determining alcohol by the measurement of Brix. I have seen many times after fermentation the Brix level falls below zero. My question is, when calculating alcohol content would I need to include the negative factor in Brix? For example, if my starting Brix is 18, I would usually calculate this by 18 x 0.56 to determine potential alcohol and get a figure of 10.08% ABV. However, if my ending Brix were -2, would I need to figure it as follows: 20 x 0.56 = 11.2% ABV?

Matt Williams

Azle, Texas

A

This is a great question. Luckily the answer is simple. You still only calculate potential alcohol based on the original Brix reading. “Negative Brixes,” or when the density of your fermented solution reads below the 0.00 °Brix mark on your hydrometer, happen because they are just that: Fermented. Alcohol is much less dense than water and when we come to the end of the fermentation and the sugar has almost all been converted to alcohol, Brix is truly only a measurement of solution density. As the relatively more-dense water and sugar solution (grape juice) gets transformed into a water and ethanol solution (wine) the new alcohol content skews the results artificially lower. There is a significant contribution from the alcohol to the ending Brix reading, which means that by the end of fermentation the Brix “reading” itself is artificially low. This means that when calculating potential alcohol we do not count negative Brix degrees as actually contributing to the alcohol level. In a way, they are like “phantom Brix units” that are really meaningless.

Estimating potential alcohol is tough, even for veteran winemakers. Things like yeast strain, fermentation temperature and dried up grapes can make it hard to first get an accurate initial Brix reading and to subsequently translate an initial Brix reading into final alcohol. Though in a lab we may say that for every degree Brix you’ll get X amount of ethanol, in reality it’s never that simple. You can certainly help yourself, though, by only using your hydrometer to help you calculate potential alcohol at the beginning of the fermentation, where it will most accurately reflect what you’ll be getting from the sugar in your juice or must.

Q

We are planning to build a pole barn where we have four small grapevines planted and I am wondering if I can cut the plants down to a little off the ground and move the plants this time of year?

Joe Melfi

Thornville, Ohio

A

Depending on the age of the grapevine, and it sounds like it could still be young since you say it’s “small,” it is indeed possible to transplant grapevines. It takes a lot of care and often takes a lot of time and elbow grease, however.

Grapevines quickly establish very deep, wide-reaching root systems and the older they are the bigger those root systems become. When you do dig out the vines, be sure to initially dig at least three feet away from the stump in order to find the rootball, dig around and under it, and move as much as you can of it. Be sure that the hole into which you move the transplant is similarly large — you may be digging a lot longer, deeper and wider than you had planned on. The roots develop many little “micro hairs” and complex and very thin root pieces that are critical for the plant’s health and are often disrupted during the move. When you do get the rootball back underground, be sure to water much more than you normally would for at least three weeks. The vine will be stressed and will be in need of extra care.

I definitely recommend waiting until late winter or early spring to attempt a transplant. At that time of the year (depending on where you live, probably around January or February), the vine will be in its most hibernation-like state. It will have had a full drink of winter rains, a replenished nutrient supply and will essentially be taking a long winter’s nap in preparation for the upcoming growing season. This is indeed why we prune grapevines in the late winter, when we effectively remove anywhere from 40–70% of the vine’s material. July and August are prime growing times for the plant, and if you knock down the vigorous green growth of the vine this time of year, the vine might not spring back. Summertime heat and dry conditions could also further stress a struggling vine, adding insult to transplant injury.

Luckily grapevines are relatively inexpensive to purchase in the case of a less than successful transplant attempt. I do fully understand the emotional attachment we can sometimes have to our grapevines, especially plants that we’ve made great wine from or have moved with us in containers from house to house.

Q

I have made several batches of plum wine but this last batch has this yellow ring that has settled around the top of the wine in the carboy. It is ready to bottle but I don’t want anyone possibly getting sick. Have you heard of this and is there any way to fix it?

Sheril Wiseman

Sedro-Woolley, Washington

A

The short story — and the good news — is that no one will get sick from this batch because no human pathogen can survive in wine. Alcohol and acidity will kill off any bacteria or yeast that could survive in the human ecosystem and make you or your friends and family sick. For example, bacteria like E. coli, one of the most common bacteria implicated in food poisoning, need an environment where the pH is closer to that of the human body, around 7.0. Wine, with much lower pH (higher acid) of around 3.5 and with an alcohol content of 10% or more to boot, is a very hostile environment for the kinds of bacteria and viruses that can make people sick. This is why folks who drank more wine and less water (pH of 7.0) during the Middle Ages were not only doing something enjoyable, they were doing something smart for their health.

“Rings around the carboy” happen frequently in winemaking, especially in fruit wines. I’ve had it happen to me at Bonny Doon Vineyard while making a peach base wine for a distillation experiment, as well as during a plum wine fermentation like yours. I found that as the fermentation level of the “must” changed during the course of two weeks, a deposit of pigment formed on the side of our fermentation buckets as the gasses escaped and the fermentation warmed up then cooled down. It looked pretty gross but the wine turned out fine — we moved the fermented fruit wines out of the primary fermentation containers before any bad bacteria or spoilage yeast had a chance to gain a foothold. This is why it’s so important to immediately rack our brand new wines to containers that are more closed and airtight once the fermentation is over. Without the protective blanket of carbon dioxide

gas produced during fermentation, new wines are vulnerable to oxidative damage, as well as to invasion by microorganisms that thrive in a higher oxygen environment.

If what you’re experiencing isn’t just a ring but is a full-blown film you may have a mold or spoilage “film yeast” issue and the wine may not age very well when bottled, or may even smell/taste funny right now. If that’s the case, you can decide if you like the wine enough to keep it.

“Ring around the carboy” is a common home winemaking phenomenon. Your wine should be totally safe to drink, though if it tastes good enough to make you want to may be another question.