Q. I am wondering how to develop more color in my reds. I keep my must outdoors and punch down twice a day. I’m worried my temperature might be too low — is temperature critical for development of color? Any other advice to get more color from my grapes?

Kent Nienaber

Ham Lake, Minnesota

A. You’re absolutely right to be thinking about how temperature affects the color of your final wine, especially if you’re fermenting outdoors. How cold or how warm a fermentation is plays a huge role in color extraction and it might just be the missing piece in your winemaking puzzle.

Color in red wine comes primarily from anthocyanins, the pigments found in grape skins. Getting those pigments out of the skins and into your wine depends on a few key factors: Temperature, skin contact, cap management, and sometimes a little enzymatic help. You’re already punching down twice a day, which is great. Keeping those skins in contact with the juice is essential for encouraging extraction, and punchdowns are an ideal way to do that. But if your must is too cold over the course of fermentation, you could be working hard without seeing the full benefit.

Fermentation temperature is one of the biggest drivers of color extraction. Warmer fermentations (generally in the range of 75–90 °F/24–32 °C) allow the cell walls in the grape skins to soften and break down more efficiently, releasing not just color but tannins, flavors, and aroma compounds. When things run too cool, which can easily happen outdoors, extraction slows dramatically. Yeast activity also lags in cooler temperatures, and since fermentation itself generates heat, a sluggish ferment can stall both your fermentation and your color development. If you suspect your red must is dipping below 70 °F (21 °C) and staying there, especially in the early days, I’d definitely recommend warming things up a bit. Even just insulating the fermenter with a blanket (electric blankets on low settings work especially well) or moving it to a warmer space can make a big difference.

Another thing to consider (and one that’s a bit underused in the home winemaking world) is the use of macerating enzymes. These are pectinase-based enzyme products designed to help break down the cell walls of grape skins more efficiently, which in turn releases more color. They’re especially helpful with thicker-skinned or less-ripe grapes where natural extraction may be more limited. A small dose at the crush or during a cold soak (if you’re doing one) can help release more anthocyanins early, when they’re most likely to bond with tannins and become stable over time. I’ve seen great results using maceration enzymes with grapes that come in a little underripe or with skins that just don’t want to give it up easily. Just be sure to follow the dosage instructions on the label as a little goes a long way.

You didn’t mention if you’re doing a cold soak, but that’s another technique you could try to enhance color. By holding your must at a low temperature for a few days before fermentation kicks off (say, in the 45–55 °F/7–13 °C range) you can allow for gentle extraction of some color compounds without pulling too many harsh tannins. This method is especially useful if you’re working with more delicate fruit or aiming for a softer, more fruit-driven red. Cold soaking does require some temperature control, so if your outdoor environment is unpredictable, it might be tricky; you don’t want to incubate spoilage bacteria. But it’s worth experimenting with if you want to boost your extraction in a gentle way.

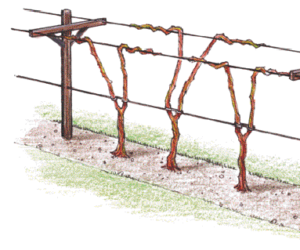

Once fermentation gets rolling, keep an eye on the cap. You’re already punching down twice daily, which can be plenty for smaller-scale fermentations. During the height of active fermentation, like when Brix is dropping over 2 degrees per day, you may want to do three or even four punchdowns daily. Make sure you’re getting good coverage by breaking up the cap and submerging it. You don’t need to be that aggressive at the beginning or the end of fermentation; once a day can be sufficient.

After fermentation, be careful with how hard you press. It can be tempting to squeeze every last drop from your skins, but aggressive pressing can release bitter, green-tasting tannins that not only muddy the flavor, but which can be difficult to remove or fine out afterwards. Press gently and taste often during this step. Sometimes the best part of color extraction is already behind you, and the goal shifts to protecting and preserving what you’ve gained.

Finally, once your wine is safely aging away and is protected from oxygen, keep in mind that color isn’t static, it evolves. If you’re aging your wine in oak, especially new or medium-toast barrels, you may actually see a stabilizing effect over time. The tannins in oak can bind with anthocyanins, forming more stable color complexes that hold up better as the wine matures. This is another great reason to follow one of the Wine Wizard’s oldest tips to the readership — ferment on 1–2 g/L of highest-quality fine oak chips. That way you start stabilizing your color right from the beginning.

To sum it up: Yes, temperature is critical to color development in red wines, and it’s likely the key area to focus on if you’re looking to boost the vibrancy of your finished product. Warmer fermentation temperatures, consistent cap management, the (not too aggressive) use of macerating enzymes, and gentle pressing practices can all work together to help you get the most from your grapes.

Q. What is the coldest a winery should be? It was so cold here in Napa, California, that I wonder if I should heat the building my wine is aging in if it happens again.

Cindy Kerson

Napa, California

A. Greetings from right here in Napa! Like you, I bundled up a bit more this past winter and kept a close eye on cellar temperatures — it was definitely one of our chillier stretches.

Your question is a great one: How cold is too cold for wine aging? The short answer is that most wines, particularly reds, are happiest aging in the low-to-mid 50s °F (10–13 °C). That range supports a slow but steady development of structure, color, and aroma. If your winery or garage space has been dipping into the low 40s or even 30s °F (low single digits Celsius) during those especially cold nights we had this winter, you’re right to wonder whether your wines might need a little more warmth.

That said, cold doesn’t necessarily hurt your wine; in fact, it can help slow things down and prevent spoilage. The bigger concern is if your wine is still undergoing malolactic fermentation (MLF) or some other active stage, in which case those colder temperatures can stall things out. If you haven’t already seen MLF finish or your wine hasn’t gone dry yet, chilly conditions can really hold things up.

Rather than heating the whole building (which, as you’ve probably guessed, can be both energy-intensive and expensive) I’d recommend thinking more strategically. Depending on how many barrels or tanks you have, and how your space is laid out, you might be able to consolidate your wine into a smaller room or corner and just heat that zone. A well-insulated side room with a space heater and a fan for circulation can often do the trick.

If you’re working on a very small scale, say with a few carboys, barrels, or stainless tanks, I’ve seen (and have used!) low-wattage electric blankets, fermentation heating wraps, or even greenhouse-style seedling mats to gently warm just one bucket or carboy. It’s a great little home winemaking hack that avoids the need to run a heater 24/7. Of course, safety first — keep cords dry, avoid overheating, and monitor with a thermometer. You want to take the chill off, not cook your wine!

If you are considering insulating or heating a larger space in the long term, I’d suggest checking out some winery-specific energy efficiency resources. Your local electric utility may have some helpful programs and tips for agriculture and small-business customers, and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Better Buildings site offers ideas for thermal efficiency and smart zoning strategies. Even something simple like adding foam board to exterior walls or using insulated curtains over roll-up doors can make a big difference in how your building holds heat through the winter months (and can have the added benefit of keeping it cooler in the summer).

The good news? You made it through the worst of the chill, and now the season has turned in your favor. Still, it’s never a bad idea to prepare for next year’s chilly season. I’m sure many of our fellow readers in much, much colder parts of the world are laughing a little bit at us, as Napa only ever sees a few days per year of real frost and we only ever see snow on our local mountain tops once every few years. That doesn’t mean we don’t all need to solve the same problems of giving our colder fermentations a few gentle heat nudges now and then.

Q. I make dry red from my estate Petite Pearl. Why does 3-year-old wine take so long to “open up”? I have to decant around three hours prior to drinking, otherwise there is not much aroma or flavor. The wine is balanced without excessive tannin.

Chuck Klimek

Franksville, Wisconsin

A. That long decant time you’re noticing — needing about three hours to “open up” in the glass — is something many winemakers (myself included) have encountered with young red wines, especially those with structure and high tannin and color content.

Your question gets at the heart of something we often associate with service and sommeliers (the art of decanting) but it’s also deeply connected to winemaking choices you make long before the cork is pulled.

Decanting works by introducing oxygen into the wine after it’s been sealed up in the bottle, sometimes for years. That oxygen helps unlock aromatic compounds and smooth out textures that may feel tight, firm, or muted at first. But the more we understand what’s going on chemically, the more we can use that knowledge to craft wines that might need a little less air to show at its best.

Since you’re already noticing that your wine isn’t overly tannic or out of balance, there are a few winemaking steps you can consider to help soften it even further before it ever reaches the glass. First, take a look at your grape ripeness at harvest. Underripe fruit can have higher acidity and slightly greener phenolics, which can contribute to a wine that feels shy or closed in its early years. Letting fruit hang a bit longer (if conditions during harvest season in Wisconsin allow) can help phenolic ripeness catch up with sugar development, leading to rounder, more expressive wine earlier in its life.

Next, be careful not to overdo it during fermentation and maceration. Over-extracting tannins (especially from seeds or stems) can create a firmer structure that takes longer to resolve, even if it’s not overtly bitter. Keep an eye on your cap management: Gentle punchdowns and shorter maceration times (especially once you reach dryness) can help reduce the harsher, more rigid tannin profiles. Acid adjustment is another area to watch. Adding tartaric acid can be important for balance and microbial stability (spoilage bacteria love higher pH/lower acid environments), especially in warmer years, but too much, especially if it’s added later or right before bottling (which I don’t recommend) can tighten up the mouthfeel. Longtime readers have heard me say this in the past: If you can make the bigger adjustments up front and earlier on, the more integrated into the final wine that change will be — whether it’s a water addition, tannin addition, or acidity adjustment. Another tip: Try to “make your adjustments in the vineyard” by picking for best balance of flavor, sugar, tannin ripeness, and acid balance.

Finally, for wines that still feel a little firm or closed at bottling, you might consider fining with a gentle protein. Traditional egg white fining — or newer vegan options like potato protein — can selectively soften certain tannins without stripping fruit. It’s a classic Bordeaux technique for a reason. If done carefully, fining might reduce the need for such a long decant. Instead of three hours to open up, you might find it drinks beautifully in one or two.

Of course, a lot depends on your fruit, your cellar conditions, and your personal style. And sometimes, a long decant just becomes part of a wine’s ritual — that little window of anticipation that makes the final sip even better.

Q. I’ve made a robust, full-bodied Bordeaux-style blend that has great flavor and aroma, but the tannins are too high. It’s been in the bottle for about a year . . . can I expect the tannins to soften over time, and how long might that take?

Lee Goodman

Baltimore, Maryland

A. Congrats on crafting a bold Bordeaux-style blend with strong aroma and flavor! That’s no easy feat, especially when you’re juggling the powerful personalities of grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Malbec, and Petit Verdot. It sounds like you’ve got a lot going right, but I understand your concern about the high tannin level and whether time in the bottle will mellow things out.

The short answer is yes. Tannins do soften with age, but how quickly that happens depends on a few things. Wine is always evolving in the bottle, and during aging tannins begin to polymerize. These longer-chain tannin molecules feel smoother on the palate than the shorter, grippy ones found in young reds. Over time, some of these polymers get large enough to fall out of solution entirely (that’s the sediment you’ll often see in older reds).

But how long will that take? With a full-bodied Bordeaux-style blend, you’re often looking at 3–5 years in bottle before the more assertive tannins really start to integrate. If you’re a year in, you’ve probably noticed some small changes, but depending on your blend’s structure, you might need a few more years before it hits that sweet spot of roundness and approachability. One thing you may try is moving a couple of bottles from the cellar into the house and comparing in a few months as the warmer temperature may accelerate the process.

That said, there are things you can do in future vintages to help tame tannins before the wine ever hits the bottle. Be sure to read my earlier response to Chuck from Wisconsin, who’s working with a red wine that also takes a long time to open up. Like Chuck, you might want to revisit your maceration strategy. Try shortening skin contact time, especially after the primary fermentation is complete, where elevated alcohol levels can start to extract harsh seed tannins.

Fining is another useful tool. Gentle protein fining, such as with egg whites or potato protein, can bind with tannins and naturally reduce astringency. It’s often used in young Cabernet blends and can shorten the “decanting window” for the finished wine. If you haven’t bottled this vintage yet you might try a small fining trial “on the bench” (using small, measured samples of the wine) to see if it takes the edge off.