SO2 Fundamentals

Of all the additives that are used in wine production, sulfur dioxide (SO2) is by far the most important, multifaceted, indispensable, and, these days, along with commercial yeasts, a contender for the most controversial. Why is SO2 so important? The timing of its use can define the style of a wine (particularly in whites); it protects wines from a myriad of spoilage bacteria; it can significantly extend the life of a wine and can be used to clean wines up in the presence of certain problems. It has been in use for storing wine for thousands of years — all that and we use it to clean too! Definitely the most important tool in a winemaker’s toolbox. Many believe themselves to have an allergy to it, although lots of foods we regularly eat contain it (dried fruits, juices, sodas, french fries, and so on), and the amount of people with a genuine sulfur dioxide allergy is extremely small. Even if drinking a full bottle of wine per day (not that I’m advocating for that), we would still likely consume more sulfites from the other foods we eat during the day. While today’s natural wine movement has proponents that are adamantly against its use, the vast majority of us would not risk producing a wine without its use.

In my opinion the treatment of sulfur dioxide, except in rare instances, is not an option in wine production. Without its use — at least before bottling — there is no guarantee that the wine you put into the bottle will at all resemble the wine you later uncork to enjoy. Depending on the style of wine you make, when you make SO2 additions relative to alcoholic and malolactic fermentations is important. Beyond this, which is basic winemaking strategy, the time you choose to add it can have differing effects, some practical, others more theoretical and philosophical, on the resulting wine and how it develops prior to bottling. Let’s review the history and the basics (I’ve heard every great basketball player say time and time again how critical it is to perfect the fundamentals), then get into some philosophy, theory, and terroir.

SO2 Historically

Although it is commonly said that SO2 has been in use in wine since the Roman times (thousands of years ago), there is no documentation of its use until the fifteenth century, where it was used as a barrel fumigant (thus used in wine being stored and aged, not fermented) (Wine Science, Jackson, 2014). More recently, in the last 100 or so years, we have come to realize the effects it can have on must before, during, and after alcoholic fermentation, and the increased amount of wine styles it allows us to make — don’t forget that that crisp, bright Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Grigio, Albariño, and dozens of other common styles for many grapes that do not go through malolactic fermentation, did not exist prior to the use of SO2 in winemaking!

Forms of SO2 In Wine

The most common form that SO2 is added to wine in the United States is powdered potassium metabisulfite (KMBS), although effervescent forms and tablets are also used. It is important to pay attention to how much SO2 your specific product contains, as they vary from product to product.

Before beginning, let’s define the different forms of SO2 in wine: Bound, free, total, and the all-important molecular. A quick summary:

• Bound SO2 represents the molecule in a state that is bound to another component in the wine, such as phenolics and acetaldehyde. When bound, SO2 has a very weak antimicrobial power.

• Free SO2 is not bound to anything in the wine, and is thus “free.” It is found in three forms: Molecular SO2, and two ionic forms, sulfite (SO3)2- and bisulfite (HSO3)–. The molecular is the form we pay the most attention to.

• Molecular SO2 is the good stuff, the most powerful form within your wine. Depending on your wine’s pH, there will be a different balance between the three free forms mentioned above, and therefore varying efficacy. At wine pH levels (2.9–4), as pH increases, the percentage of molecular SO2 decreases and the percentages of the less potent ionic forms increase — this is why lower pH wines require less SO2 addition for protection. Thus, it is ideal to base your SO2 additions on maintaining your desired molecular SO2 level, as opposed to the level of free or total SO2 in your wine. The usual recommended level of molecular SO2 to maintain in wine for all-purpose protection is 0.8 mg/L (ppm) for whites, and somewhat less (as low as 0.5 mg/L) for reds.

• Total SO2, therefore, represents the sum total in wine, both bound and free.

How to determine all this at home? Tables showing the corresponding levels of free SO2 by pH are easy to find online. pH meters can be found for under $20 for the stick forms, but you will get a much more reliable instrument that provides more accurate and precise readings for around $125 (get one with a temperature probe, as temperature affects readings). Skip the pH strips, with practice, your tongue can be much more accurate (although I wouldn’t recommend basing SO2 additions on it!). The more difficult metric to determine at home is level of SO2, however, you can send in a sample of your wine to a wine lab such as ETS Laboratories, who provides inexpensive and very quick results. Most yeast strains produce around 10 mg/L of SO2 during fermentation, but some as high as 60+ mg/L, so testing is important if you want to be precise. On the one hand you cannot assume zero if you have not added any SO2. On the other hand, you cannot assume that the SO2 produced by the yeast cells are going to remain in the free form for the duration of the winemaking. You can, of course, estimate all of this. I did as a home winemaker and never had problems (adding 50 mg/L after fermentation and another 30 or 40 prior to bottling before the next harvest), but, in this article, we’re more concerned with being precise.

SO2 Before Fermentation

Unless your fruit is highly diseased or damaged, I would discourage you from adding sulfur dioxide to your grapes prior to crushing reds or pressing whites (i.e. for transportation). The distribution will be inherently uneven and will therefore be ineffective.

Sulfur dioxide has significantly more inhibitory power against bacteria versus yeast (this includes Brettanomyces, against which it does little). When added prior to alcoholic fermentation, it can inhibit or destroy bacterial and yeast populations that came in on the fruit, which you may or may not want playing a part in the development of your wine, and can also help keep “native” yeasts in check while allowing the yeast you choose to take hold of the fermentation (although this is never a guarantee).

It is also a powerful agent, prior to fermentation, at blocking the enzymes responsible for must oxidation. SO2’s effect that serves to block oxidation directly (discussed more during SO2 and post-fermentation later) is very slow, and the protection your must receives from SO2 at this point is from its ability to inhibit enzymes that facilitate oxidation. Once added to must, this effect begins quickly, within minutes of addition.

SO2 and Malolactic Fermentation

Regarding acidity and ML bacteria, if you are creating a bright white wine and want to retain as much malic acid as possible, it is advisable to add SO2 to your must, as malolactic bacteria can be at play during alcoholic fermentation and convert a portion of your malic acid into lactic (note, even if ML is blocked, various strains of Saccharomyces yeast consume significant portions of malic acid, up to 25% or more. SVG, a common Sauvignon Blanc yeast, is an example).

For wines destined to go through full or partial ML, skip this addition, or do not add after alcoholic fermentation. Once ML has completed, or reached the level you would like, add SO2 to achieve a molecular level of 0.8 mg/L (remember, this will be dependent on the pH you measure in the wine) to halt microbial activity. It is important to mention that a cool cellar temperature is important to keep ML activity from beginning or continuing after it has been blocked, and the recommended 0.8 mg/L on its own may be insufficient at malolactic bacteria’s preferred temperature (65+ °F/18+ °C) for extended periods.

SO2 In Wine Aging

If you wait until ML is complete or has reached your desired level, an SO2 addition now will help protect your wine against chemical oxidation and microbial infection, and you can maintain your desired level(s) of ML until bottling. For wines aging on their lees, being precise in using the lowest level of SO2 possible is ideal, as SO2 can encourage the development of off odors (H2S and mercaptans) in lees.

SO2 binds with various phenolics, including color molecules (this is why SO2 can temporarily bleach color), which, for reds just after fermentation, means those color molecules that bind with SO2 are not available for binding and stabilizing with tannins. Also, SO2 short circuits the process by which color and tannin ideally polymerize, thus SO2 added at this time can have adverse effects on wine structure and longevity. Most color/tannin binding happens within the first 6 months of aging, so additions after 6 months would be the preferred timing, unless you are finding any spoilage bacteria odors prior to that. Reds this young, due to their own use of oxygen in this binding process, are at low risk for chemical oxidation, as little oxygen will be freely available in the wine.

Philosophy, Faith, Assumptions, Terroir, and the Future

Reading all of this, and the associated risks involved in skipping SO2 use, one may wonder why anybody would question the use of such a valuable tool. The reason is terroir. Terroir is the French term for both the characteristics of a wine that result from its particular vineyard site, as well as to the vineyard site and its unique characteristics which lead to specific attributes in a wine (weather, soil, and so on). These days, particularly by those proponents of today’s natural wine movement, the belief that the yeast and bacteria found within a vineyard (and on grapes grown in that vineyard) are a part of terroir is common, so the ability of SO2 to kill these microbiota would therefore be a threat to creating an authentic wine from a particular place. I have customers who regularly ask about a winemaker’s SO2 practices, and the occasional one who will not buy wines that were made with anything other than grapes, with the exception of a “low level” of SO2 just prior to bottling.

Everything around us is covered in bacteria and fungi, and grapes are no exception. When they arrive to the winery, grapes are covered in an immense diversity of microbes (yeasts included). Recent studies from UC-Davis and around the world are showing there to be consistent populations of specific microbiota on grapes between growing regions, vineyards, grape varieties, parts of the grapevine (fruit vs. stems vs. leaves, etc.) and even down to individual blocks in a vineyard! For a brief explanation from one of the initial studies on this, search for “Local Microbes Can Predict Wine’s Chemical Profile, Study Finds” on the UC-Davis website, by Pat Bailey.

Most of us don’t question that the weather, soil, aspect, slope, and other various and consistent factors that contribute to vineyard’s terroir have an effect on the resulting flavor profile of a wine. So the idea that there are microbiota that are particular and consistent in vineyard that can have an effect on the wine implies that microbiota should be included in the list of things we refer to as terroir, and that they have a warranted place in the production of a wine.

How might this belief affect your winemaking? It has become commonplace in small production winemaking, particularly those winemakers who consider themselves natural producers, to forgo the use of SO2 during the winemaking and aging process, allowing any present microbiota to exert their effect on a wine. But skipping SO2 before bottling has proven to lead to immense bottle-to-bottle inconsistency (often in the form of glaring volatile acidity and other “defects”), so most of these winemakers now add SO2 prior to bottling.

It is important to mention here that although grapes are covered in microbiota from the vineyard, there is little Saccharomyces cerevisiae on them, and that the vast majority of “native” yeast genera found on grapes die at around 7% alcohol. That means a wine undergoing spontaneous ferment will ferment from 7% alcohol until dry with a yeast more likely found in the winery, picking bins, etc. — not the vineyard. There is also no guarantee that the microbiota at work in a wine all come from the vineyard, as the grapes will be exposed to other microbiota before beginning fermentation, from the air and various surfaces they touch.

Many of these wines are squeaky clean and extremely well made, but, in making wine this way, we are of course risking having a wine riddled with acetic acid, ethyl acetate, strange bacterial aromas (“mousy”, geranium, and so on) as well as the myriad of quality degrading effects of numerous lactic acid-producing bacteria (of which we currently understand little). The flavors of a wine that result directly from the other aspects of terroir (climate, soil, and so on) can quickly be eclipsed, or at least muddled, by these technically defective compounds. So, is it worth it?

In the coming years, or more realistically decades, we will have a much better understanding of what these preliminary studies are beginning to shine light upon, which is ultimately if and what these apparently consistent and site-specific microbiota are doing to a wine, and if they are actually contributing in a significant way to the resulting flavor of a wine.

The aspects of terroir that garner the most attention (microbiota and soil type [granite vs. calcareous vs. volcanic, and so on]) seem also to be the most mysterious, which we understand the least, and, which have the most illusive and unspecific effects on wine flavor. I argue that it is the ones we understand the best (weather, sunlight intensity, aspect, effect of soil structure and texture [sand vs. clay, for example]) that have more concrete, consistent and impacting effects on wine flavor, and that therefore have a more significant effect in defining a wine’s character. It would follow, in my brain at least, that it may not be worth risking the clarity of the more prominent terroir-derived characteristics, in hope of gaining other, less impacting and more evasive ones. This doesn’t take into consideration the inevitable effects of man on grape composition (clone/rootstock selections, canopy management, soil management, and so on.)

In my opinion, forgoing the use of SO2 to allow “native” microbiota to freely participate in a wine’s development takes a high degree of faith in their significance relative to the other aspects of terroir, which we better understand and whose effects we can better interpret. There are winemakers I have a tremendous amount of respect for in both camps: Those for whom SO2 is the first thing they add to their must, and those who would never use it prior to bottling. Amazing wines are made in both ways, and I don’t think it is possible to definitively say at this point what method produces the most terroir-authentic wines.

Bringing It All Together

What do I personally do with all this information? For the time being, my winemaking practices fall somewhere in the middle with respect to microbiota and terroir. For reds I have usually forgone the use of SO2 until bottling; for whites that go through ML I have waited until a touch of chemical oxidation has appeared before addition, and for whites that will not go through ML, it is of course the first thing I add prior to fermentation. I like the idea that there may be microbiota from the vineyard that may leave a distinct stamp on my wine, and want to give them as long as possible to exert their effect — that said, I am very sensitive to VA and most so-called defects in wine, and do not want to risk their appearance in my wine. I would hate for them to overshadow the aspects of a wine’s terroir, those aspects I better understand and trust. So, I inoculate with neutral commercial yeasts and ML bacteria, which in their vigor and high populations may destroy most of the “native” microbiota anyway, in which case there may be no vineyard microbiota having any effect.

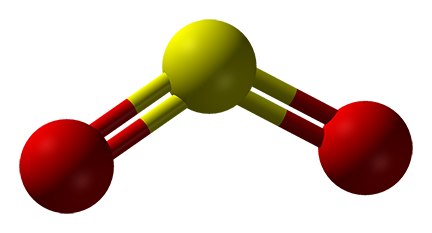

It’s amazing to me that something as simple as a sulfur atom covalently bound to two oxygen atoms can be of such significance. A little powder that you add to your wine that can be used in a myriad of critical ways, lauded by many, demonized by some, but regardless with very far reaching implications. I’m excited to see how the debate about SO2 develops as more research comes out. I’ve heard there are alternative products being developed, and it will be interesting to see if they can match SO2’s versatility, and what theoretical issues they themselves bring up. For the time being, I’ll continue to use SO2 to safeguard my wines at various points in production, as I weigh the risk/reward of its use. It’s an indispensable product in winemaking at one point or another, no matter what your stance is.