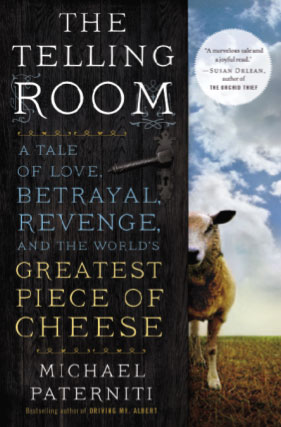

The Telling Room

In THE TELLING ROOM, author Michael Paterniti finds himself in the Castilian village of Guzmán where he is sucked into the heart of a blood feud that includes accusations of betrayal and theft, death threats, and a murder plot all revolving around cheesemaking. Here is an excerpt:

Ambrosio navigated a patch of detritus — old planks with rusted nails at weird angles and shatters of broken glass — and rounded a corner to a small tack room. In the darkness it was hard to make out much until three metal forms appeared, glowing like spaceships from an old movie. Ambrosio smiled. It was here where he made the family’s wine — 1,200 bottles to carry them through a year* — and he wanted

to check his latest batch, which was nearly ready.

“The grapes were very good this year,” he said. “We may have our best wine yet.” A long-stemmed glass appeared in one of his hands, and with the other he removed the lid from one tank and dipped the goblet in. He held it up in a single blade of clean light, admiring the wine’s color, which was actually many colors: There were carmine and amethyst and plum, worlds within worlds. Ambrosio poked his nose into the glass, inhaled, then took a long sip.

He licked his lips, pressed them together, contemplating, then nodded . . . yes. He swirled the goblet, watching as clear glycerin gripped the sides and slipped down as liquid plane settled upon plane, then repeated the whole thing, ending with a long, loud, gurgly sip.

“Puta madre, está bueno!” he said. “Here, some lunch.” He filled a glass and pushed it toward me. I drank — and once more. Ambrosio refilled our glasses, and we drank again.

“When you put something alive in your mouth,” he said, “it makes you more alive. The people who produce wine are mostly pedantic and stupid,” he continued, jabbing the air with his glass, sloshing the dregs. “They don’t make wine; wine makes itself, God makes wine. They may keep things clean and in good order, but the grapes make the wine. Whenever I serve my wine, not only is it cold, but there’s an aroma that invades the whole table. You have to listen for what the wine itself says, not the people who make it. And worse are the people who buy the expensive stuff. They don’t know shit! They couldn’t care less about the aroma and finer nuances of drinking wine. They don’t hear a thing the wine is saying.”

We lingered in the tack room until we were feeling mighty and powerful. Then Ambrosio led us out of the storehouse, tromping along a footpath that transected a fallow field below the town, circumventing the village itself.

*It averaged out at about 3.2876 bottles a day, shared primarily by Ambrosio, Angel, and their father, and yet this was deceptive because they seemed to drink so much more, at the bar or visiting with compadres, from bottles that were given to them, for the exchange of homemade wine was a custom among friends. It seemed the 1,200 bottles were truly meant as a foundation. Some years, as Ambrosio said, “my father drinks so much, we have to go out and buy much more. He drinks so much he has a groove in his front tooth where the stream from the porrón has worn it down.”

In THE TELLING ROOM, author Michael Paterniti finds himself in the Castilian village of Guzmán where he is sucked into the heart of a blood feud that includes accusations of betrayal and theft, death threats, and a murder plot all revolving around cheesemaking. Here is an excerpt:

Ambrosio navigated a patch of detritus — old planks with rusted nails at weird angles and shatters of broken glass — and rounded a corner to a small tack room. In the darkness it was hard to make out much until three metal forms appeared, glowing like spaceships from an old movie. Ambrosio smiled. It was here where he made the family’s wine — 1,200 bottles to carry them through a year* — and he wanted

to check his latest batch, which was nearly ready.

“The grapes were very good this year,” he said. “We may have our best wine yet.” A long-stemmed glass appeared in one of his hands, and with the other he removed the lid from one tank and dipped the goblet in. He held it up in a single blade of clean light, admiring the wine’s color, which was actually many colors: There were carmine and amethyst and plum, worlds within worlds. Ambrosio poked his nose into the glass, inhaled, then took a long sip.

He licked his lips, pressed them together, contemplating, then nodded . . . yes. He swirled the goblet, watching as clear glycerin gripped the sides and slipped down as liquid plane settled upon plane, then repeated the whole thing, ending with a long, loud, gurgly sip.

“Puta madre, está bueno!” he said. “Here, some lunch.” He filled a glass and pushed it toward me. I drank — and once more. Ambrosio refilled our glasses, and we drank again.

“When you put something alive in your mouth,” he said, “it makes you more alive. The people who produce wine are mostly pedantic and stupid,” he continued, jabbing the air with his glass, sloshing the dregs. “They don’t make wine; wine makes itself, God makes wine. They may keep things clean and in good order, but the grapes make the wine. Whenever I serve my wine, not only is it cold, but there’s an aroma that invades the whole table. You have to listen for what the wine itself says, not the people who make it. And worse are the people who buy the expensive stuff. They don’t know shit! They couldn’t care less about the aroma and finer nuances of drinking wine. They don’t hear a thing the wine is saying.”

We lingered in the tack room until we were feeling mighty and powerful. Then Ambrosio led us out of the storehouse, tromping along a footpath that transected a fallow field below the town, circumventing the village itself.

*It averaged out at about 3.2876 bottles a day, shared primarily by Ambrosio, Angel, and their father, and yet this was deceptive because they seemed to drink so much more, at the bar or visiting with compadres, from bottles that were given to them, for the exchange of homemade wine was a custom among friends. It seemed the 1,200 bottles were truly meant as a foundation. Some years, as Ambrosio said, “my father drinks so much, we have to go out and buy much more. He drinks so much he has a groove in his front tooth where the stream from the porrón has worn it down.”

From the Book, THE TELLING ROOM by Michael Paterniti. Copyright © 2013 by Michael Paterniti. Reprinted by arrangement with The Dial Press, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.