Winemaking isn’t brain surgery, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy either. Even in the most picture-perfect growing seasons, challenges arise that force a winemaker into tough, on-the-fly decisions that can make or break a wine in a matter of moments. There’s no time to ruminate; action must be taken, and this action can change the trajectory of the wine, for better or worse. Often, these decisions mean the difference between good wine and great wine; in the most dire of cases, they mean the difference between wine and vinegar. We’re well acquainted with this idea here in New York’s Finger Lakes region. Our cool, damp climate presents a host of challenges that can be maddening to even the most seasoned cellar rats. But if you’re a Riesling fan, and I most certainly am, there’s no better place to ply your trade. Using a Riesling wine I made this past harvest, grown in some of the toughest of conditions we’ve faced and causing a lot of on-the-fly decisions, I’ll share a case study of one particularly pesky wine, the decisions I faced, and remedies I threw at it. While the challenges you’ll face sooner or later may be similar or entirely unique to my own situation, I hope that this insight gets everybody thinking about what can happen, and how to approach challenges when they arise.

Riesling didn’t bring me to the Finger Lakes wine region, but it set its hooks over the last 12 years. This grape’s unmatched versatility and food-friendliness are a dream for any young winemaker looking to forge their own path.

In my short career as a professional winemaker, I have had the opportunity to produce just about every style of Riesling I could imagine; bone dry to late-harvest sweet, skin-fermented to sparkling — I’ve tried every style I could get away with in my pursuit of understanding this noble grape. Well, every style except one. Until 2021, there was one traditional iteration of Riesling I had yet to attempt: Süssreserve.

Süssreserve

Popularized in Germany, süssreserve (translated to “sweet reserve”) is a winemaking technique in which unfermented juice is blended to a nearly finished fermentation to add sweetness and temper alcohol. It’s not uncommon to leave residual sugar in Riesling, in fact it’s often necessary to balance its trademark acidity. Typically this is achieved by arresting the fermentation via chilling and/or filtration before it reaches full dryness. With süssreserve, however, the addition of unfermented juice at the end of fermentation delivers a more robust array of unfermented sugars and organic acids, having a unique effect on the sweetness, balance, and aromatic complexity of the finished wine. The correlated drop in alcohol content further reinforces this shift to a fresher, livelier profile.

Süssreserve Rieslings had been on my radar since I first set off to pursue winemaking, but they re-entered my awareness with a Canadian example I encountered on a visit to the Niagara region in the winter of 2018. Its fresh fruit, balanced sweetness, and sprightly acidity occupied space in the forefront of my mind for months following that tasting. I knew that as soon as I had a chance, I needed to attempt one of my own. It would be a few years before that opportunity materialized, but in the months leading up to the 2021 harvest season, the pieces finally appeared to be falling into place. The right fruit, resources, and strategy were all there. As I salivated over the vibrant, juicy Riesling that could be, Mother Nature stood by, ready to increase the degree of difficulty that laid ahead.

A Tale of Two Vintages

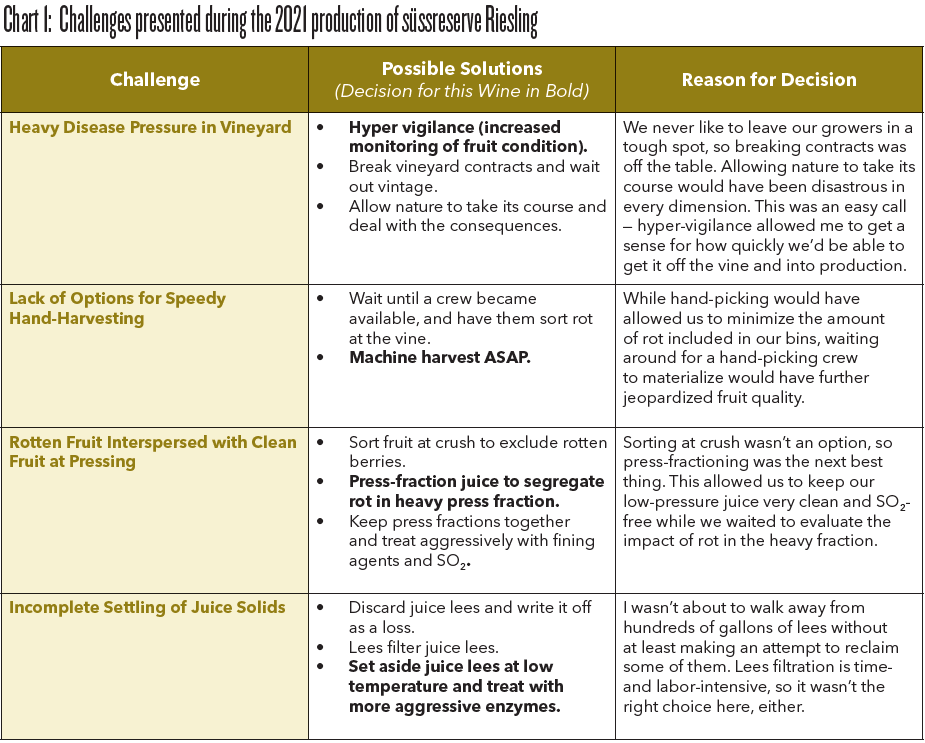

Viewed purely through a winemaking lens, 2020 in the Finger Lakes was about as picture-perfect as anybody could imagine; 2021, well . . . not so much. The 2021 growing season opened with plenty of promise — an unusually warm spring got us off to an excellent start. As spring turned to summer, however, consistent rain accelerated disease pressure. By the time fall rolled in, things only got worse; as deluge rains split berries and bunch rots exploded in vineyards throughout the region. Given these conditions, you might expect a winemaker to play it safe and cut their losses, but I’ve never been one to do things the easy way. Tough vintages give you the opportunity to test your skills in the face of adversity, and I wasn’t about to let that opportunity slip away.

I understood that if I was to pull off a süssreserve Riesling that lived up to my expectations, I’d need to source the fruit from a vineyard that knew how to navigate a difficult year. Luckily, I had just the farm. Airy Acres Vineyard on the west side of Cayuga Lake is a relative newcomer as far as Finger Lakes grape growers go, but they’ve quickly become one of my favorite vineyards for Riesling. The Bassette family, who owns and manages the vineyard, takes an innovative and hands-on approach to growing premium fruit, and that meshes perfectly with my approach to winemaking. We started sourcing fruit from Airy Acres in 2018, a vintage with challenges that bore shocking resemblance to those we encountered in 2021. The Bassettes and I learned a lot about their farm’s potential in 2018 — even in a rough year, the Riesling we produced was so stunning that we opted to leave most of it as a single-vineyard reserve offering. In the vintages that followed, we learned how beautifully their Riesling held onto its acid — even in warm years — making it the perfect building block for wines with residual sugar.

Vigilance in the vineyard is critical in any winegrowing season, but it’s even more important in a difficult vintage. I generally start monitoring fruit development immediately post-veraison, walking the rows on a weekly basis until the fruit is harvested. In most years, I’m keeping close tabs on ripeness and cleanliness, making suggestions to the grower about projected harvest timelines and any proactive or reactive measures that may be taken to prevent or reduce any disease pressure that may arise. In years like 2021, there’s a sense of sacrifice attached to these visits; the disease pressure is already there, so I’m left pondering how much more ripeness can be gained week-to-week and weighing that against the prospect of losing tonnage or quality should the disease become unmanageable. By the third week of October, I’d seen enough: Enough ripening to know I had something I could work with, enough Botrytis to know that the spread of rot was accelerating, and enough rain in the forecast to know that this was no time for indecision. It was go time.

Pressed for Time

The Riesling finally came off the vine on October 20. Due to the almost-universal labor shortage of the past year, we opted to sacrifice selectivity for speed and harvested the fruit mechanically. In a perfect world, hand-picking would give us an opportunity to sort rotten bunches at the vine, ensuring that we had the cleanest possible grapes to process, but if there was a theme to the 2021 harvest season, it was that we weren’t existing in a perfect world. We had to get this Riesling off the vine and onto our crush pad as quickly as possible.

When the fruit arrived, we started processing it right away. Harvest data was as follows: pH: 3.02, TA: 7.95 g/L, and 18.4 °Brix. It was crushed directly into a horizontal membrane press and treated with two different pectic enzymes: Scott Labs’ CinnFree and HC. In order to minimize the sensory impact of the bunch rot that was present, the press fractions were separated: Low-pressure juice (extracted under 0.75 bar of pressure) and high-pressure juice went to separate tanks for chilling and settling. The idea here being that more of the rot-driven flavors and aromas would be present in high-pressure juice; this would allow us to keep the low-pressure lot clean, while presenting an opportunity to assess and correct any flaws in the high-pressure lot. I’d use the light-pressure juice for my süssreserve fermentation and blend the high-pressure juice for other products. Though it may seem foolish given the condition of the fruit, I opted not to add any SO2 at pressing. I employ several non-Saccharomyces yeasts in our Riesling fermentations, and they have notoriously weak sulfite tolerance. Adding SO2 at this stage might prevent wild fermentation, but it’d also limit my ability to push in the stylistic direction I wanted.

The Airy Acres lot wasn’t the first Riesling we harvested in 2021, but it was in very similar condition to the other lots we’d harvested previously. I had an idea of what to expect from cold settling: It would be problematic. The colloids contributed by ever-present Botrytis prevented juice and solids from separating as cleanly as I would have liked, so I opted to hold the juice at 35 °F (2 °C) for a whole week, hoping that extended settling time would increase my yield. When I proceeded to rack, however, these hopes were dashed; of 515 gallons (1,950 L), only 316 (1,200 L) were clear enough to ferment. This wasn’t going to work for me — I’m almost pathologically waste-averse, so I pumped as much of the remaining lees as possible into an IBC (intermediate bulk container) and tucked it into our walk-in cooler for a longer, more aggressive clarity enzyme treatment with Scott Labs’ heavy hitter: Spectrum.

Ferment to Be

Following settling, I allowed the little juice I was able to clarify on the first attempt to warm for two days prior to inoculation. The fermentation was initiated with Flavia, Lallemand’s preparation of Metschnikowia pulcherrima. Flavia is my preferred non-Saccharomyces yeast for most of our Riesling fermentations, as it amplifies the concentration of both thiol and terpene precursors while also producing glycerol, a textural component that is of great help in balancing acid. Non-Saccharomyces yeasts are great for getting fermentation started, but they’re not equipped to carry it for more than a few percent alcohol – — for that I turned to my other favorite Riesling yeast: Anchor’s Exotics Mosaic.

After two days of fermentation with Flavia, the Riesling was inoculated with Mosaic. This unique hybrid Saccharomyces strain has quickly become one of my favorites across the board, but especially for Riesling. Mosaic reveals the rich tropical and stone fruit aromas present in Riesling, and can reliably be stopped by crashing the fermentation temperature — a very attractive attribute for leaving behind residual sugar. The fermentation was allowed to run cool and slow, proceeding for 19 days at 58 °F (14 °C) before the Brix fell below zero.

In the time it took for the clarified juice to ferment, I’d decided that my reclaimed juice lees were just the piece I needed for my süss addition. After a few weeks and several additions of Spectrum, I managed to clarify a substantial portion of the muck that I’d set aside at the initial juice racking; when the fermentation fell below 0 °Brix, I blended in enough juice to increase the overall volume by 20%, driving the sugar up to 4.4 °Brix. Following this addition, I allowed the fermentation to proceed overnight in hope of reinvigorating some esters before crashing the tank temperature the next afternoon; in that time the sugar reading had fallen to 3.9 °Brix. The wine was held at 35 °F (2 °C) for two days and was subsequently racked and centrifuged to remove any remaining yeast. The finished product was cold stabilized and sterile filtered, landing at 41.64 g/L residual sugar and 8.8% ABV.

Was the Süss Worth the Fuss?

At the time of this writing, our 2021 süssreserve Riesling is awaiting bottling. It’s destined to become part of a new series of wines introduced under our Montezuma Winery brand last year: Voleur. French for “thief,” Voleur wines are my love letters to the wine regions and winemaking traditions that made me choose this crazy profession in the first place. These are wines with big personalities and stories to tell, and boy does this Riesling have a story.

Set in one of the world’s great Riesling regions during one of said region’s tougher vintages, it’s got Old World inspiration, New World innovation, and a cast of characters that range from forward-thinking farmers to a scrappy winemaking team that sometimes bites off a little more than it can chew. There’s anticipation, plot twists, narrowly avoided heartbreak, and, most of all, triumph. I’ve done my best to tell that story here, but by the time this article is published it’ll be more than ready to speak for itself. I’d highly recommend you track down a bottle and hear it out.