Q. I got into a bit of a kerfuffle with my housemate the other night. We were having friends over and he said, “No way, you can’t open a red. We’re having grilled chicken and the neighbors are bringing a salad. That’s white wine territory.” I happen to be a red wine drinker, and I had to wonder, “What year is this that we’re still repeating the “white wine with white meat” so-called rule someone called gospel a century ago?” I proceeded to open my Pinot Noir, but then became curious. Wine seems so full of rules and regulations that have taken on mythical status. What are your favorite wine myths that need to be debunked?

Abigail Banks

Madison, Wisconsin

A. You’re a reader after my own heart! Yes, the wine industry seems to have made life more difficult for itself by inventing (and continuing to promulgate) a litany of “to dos” and “don’t dos.” Without further ado, dear readers, to follow are a few of my favorite wine consumer myths that are in need of dubunking.

“Serve reds at room temperature”

Though especially welcome in summertime, and especially tasty with regards to Pinot Noir, I break this “rule” year-round and with many varietals to boot. In the depths of December, you can still find me putting a slight chill on many reds, from a Beaujolais Nouveau at Thanksgiving up to some burly Syrah on Valentine’s Day. I just like my reds served a little cool and find that I prefer around 50–58 °F (10–14 °C) or so, far below “room temperature.” Summertime, however, is when I’m most likely to put a red on ice. “Room temperature” in our house in Napa doesn’t mean 68 °F (20 °C) like it does in November and as ambient temperatures rise, my tolerance for the more volatile components in red wines (i.e., alcohol, aldehydes, and volatile acidity) goes down. I find it hard to appreciate a red wine when it’s so warm even its modest 13.8% alcohol hits me like a ton of grapes. Solution? Use a tabletop wine cooler, an ice bucket, one of those stick-it-in-the-bottle gadgets like the Corkcicle or simply stick the bottle in the fridge for 30 minutes. A slight chill can focus aroma, tame the perception of alcohol, and can make a red seem more refreshing, especially when the weather heats up.

Anyone who doesn’t like this “cool take” will hate my next one!

“Never put an ice cube in your wine”

One of my favorite professors at UC-Davis, the late great Ralph Kunkee always said, “It’s OK to put an ice cube in your wine, as long as you know you’re really not supposed to.” What he meant was, it’s perfectly fine to increase your hedonistic pleasure in the moment, as long as you appreciate the chemistry behind it. By adding ice, you’re cooling it down as well as adding a little bit of water, so you’re making the wine’s serving temperature more to your liking while slightly diluting the alcohol, tannins, acids, and other flavor compounds. Interestingly, while chilling depresses the kinetic energy, and hence the availability of all aromas in the headspace, you also may be liberating additional aromas because of the changed isoelectric point, surface tension, and alcohol content of the libation. This is why adding water and/or ice to whiskey is such a hot debate, with proponents on either side.

OK, sorry to get all geeky on you, but the long and short of it is that adding an ice cube to wine subtly changes the chemistry of the beverage, beyond what the winemaker intended, and with consequences that are difficult to predict. However, adding that ice cube may increase your enjoyment of that glass of wine, and for those who knew Ralph, one of the things that made him so beloved was his unstinting pursuit of increased enjoyment in life. As a winemaker, I give you permission to stick an ice cube in your glass of wine (and to serve a Pinot with salad). I agree with Ralph: The world needs more enjoyment.

“Screwcap Means Cheap”

Approximately 30% of the U.S. wine market is packaged under screwcap, whereas in some countries, like New Zealand, they account for almost 90% of production! The cork is not threatened, but the screwcap is becoming very widely accepted in the U.S. (though the U.K. and Australia also have had us beat for a while). Especially in whites, pink wines, and Pinot Noir (which I believe has more to do with perceived consumer acceptance and conservative marketing than actual wine aging dynamics), screw caps (AKA “twist-offs”) are to be found everywhere and in every price point. In the past they were for commercial wineries only (you need a specialized machine to roll them on), but more and more home winemakers are giving new plastic hand-applied “twist and seal” screwcaps a try. I’m still not 100% sold on their long-term ageability but I do think they could work great for soon-to-consume wines.

We should remember that without the development of the cork and bottle combo in the eighteenth century we would not have been able to develop a taste for bottle-aged wines. I also think that while most winemakers will admit cork isn’t perfect, many feel that screw caps offer a viable and more consistent alternative, especially in a world where probably 99% of wine is consumed within a year of purchase. Then there’s the wine industry’s face-palm factor: Can you think of any other commercial sector that goes to such lengths to actively put barriers (the need for a corkscrew) in front of accessing and enjoying its product? I believe in convenience, and evidently so do a lot of other winemakers and wine drinkers. Anecdotally, in my house (and I bet in many others), more and more often, the first bottle out of the fridge or wine cabinet is one with a screw cap. As more and more of us in the wine business have had good experiences with using screwcaps for our wines and as more and more consumers get used to them, I think that 30% usage rate will continue to grow.

“Real (fill in the blank) don’t drink pink wine”

This ain’t your grandmother’s white Zin, kids, and there are so many great reasons to give pink a try that you’re missing out on a lot if you still think rosé wine is for little old ladies. Though we should give credit to Beringer White Zin for pioneering the category on the palates of the masses over 30 years ago, today’s crop of pink wines (AKA “blush,” “saignée,” or sometimes “oeil de perdrix”) are increasingly made in drier, more acidic styles that are appealing to wine geeks and wine newbies alike. Because they come from lightly pressed red grapes, they benefit from additional aromatic and textural complexity and therefore are very versatile when it comes to food pairings. Additionally, because they are early-release wines and don’t incur months’ worth of barrel age (and the associated costs), pink wines tend to be extremely affordable as well. So what have you got to lose except some preconceived notions?

“Great Wine is Expensive”

As recently as the 1970s there were under 500 wineries in the U.S. Now there are over 11,000. It should therefore come as no surprise that we as consumers have so many more choices than ever before, in many different styles, regions, and price points. Though I’m a California girl and tend to root for our domestic producers (go team!), I never hold back cheering on my international winemaking friends and acknowledge that globally, we’re one big international wine market. Because of currency swings, the variations in climate and season, and not to mention labor and production costs from place to place, someone’s always gonna have a tasty deal somewhere. Especially with fresher and earlier-to-bottle styles (meaning fewer storage costs and cheaper to produce) so enjoyable, whether it’s a racy Pinot Gris from Clarksburg, a Rhône-based red blend from Paso Robles, or a Grüner-Veltliner from Austria, it’s pretty darn easy to find a great bottle of wine for under $20. Online wine research is fine, but I believe nothing beats the personal recommendation from a friend or your favorite wine store employee. Want a big bang for your buck? Spend some of your time getting to know the staffers at a wine bar or wine shop in your neighborhood. They’ll get to know you and your preferences, and you in turn will reap the benefit of their experience as they “filter” their selection to your tastes and budget. In the search for great wine deals, face time still counts.

Q. I inadvertently added the wrong yeast to a batch of Chardonnay. I intended to use D-47 but picked up Red Star’s Côte des Blancs. it was four days into the fermentation before I caught the mistake. I immediately went online to learn about the qualities of Côte des Blancs and found it is not recommended for malolactic fermentation (MLF), which I had planned on doing. why is Côte des Blancs not recommended for MLF? If I do inoculate, what are the downsides? Any suggestions?

Brian Henderson

Benicia, California

A. I’m glad you wrote in this question. It points to the importance of thinking about our wines in the big picture sense (not to mention the importance of double checking before making additions). Decisions we make in the beginning can affect what decisions we may be able to make (or are forced to make) later on. In your case, you’re worried that your choice of yeast (Côte des Blancs) may keep your Chardonnay from going through malolactic fermentation later. The bad news is that yes, it may prevent it, but the great news is that there are a couple of things you can do to mitigate the problem.

First off, let’s talk a little more about your yeast. Côte des Blancs yeast is a very hungry yeast and a very “gourmet” eater. What this means for fermentation is that Côte des Blancs, while it chews through the sugar in your Chardonnay, is also gobbling up the amino acids, nitrogen, vitamins, and other micronutrients vital for a healthy fermentation. Unfortunately, malolactic bacteria happen to be what microbiologists call a “fastidious” fermenter. Like yeast, they too need some of these same micronutrients to survive, grow, and thrive. The good thing is that you can preemptively feed your juice or must with a well-balanced yeast food mix sold by companies like Lallemand, AEB, ATP Group, Laffort, etc. There are a lot of alternatives out there on the market — just pick a balanced one without a lot of diammonium phosphate, which one winemaker I used to work with called “junk food for yeasts.”

If you use a nutrient-needy yeast like Côte des Blancs you should also supplement your new wine with a malolactic booster like Opti Malo Plus after primary fermentation is over. These MLF-specific mixes carry a laundry list of micronutrients especially formulated to meet the needs of malolactic bacteria. I sometimes add a small dose of MLF nutrients to my wine anyway if I suspect I have any conditions that may inhibit malolactic fermentation like high alcohol, low pH, or low temperature. Malolactic bugs are notoriously picky about their environment, so it’s important to coddle them a bit to encourage them to do their job. Partial-ML wine must be stored cold or sterile filtered, both before and during bottling, in order to prevent this from happening. So unless you have the capability to do so (and not all micro-producers or home hobbyists do), then I suggest people put their whites through the malolactic fermentation for stability reasons.

Q. I have a batch of 2024 Viognier (I had frozen grapes shipped to me) that has completed primary and secondary fermentation. It tasted flabby so I had it tested for pH and titratable acidity (TA). The TA was low at 0.444 g/100 mL and the pH was 3.66, so a little elevated for a white wine. I bench tested two 100-mL samples to try to dial it in. The first with 1 g of tartaric acid and the second with 2 g, thinking that I needed to reduce the pH to 3.4 to be safe. Both of the samples were too tart for my taste, as well as others’ who sampled them. For wine stability, should I add the 2 g/100 mL and then wait to see if the tartness will dissipate, and if it doesn’t, then reduce the acid with potassium carbonate?

Gary Smith

Omaha, Nebraska

A. Bravo to you for doing bench trials! If you’ve read my columns over the years you know that doing bench trials — that is, testing a wine treatment on a small scale (“on the lab bench”) before performing it on your entire lot — is one of my most oft-repeated mantras. You also followed another of my key winemaking axioms — let your taste buds be your guide.

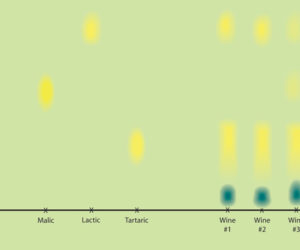

Yet another nugget of winemaking wizdom I often pass on to readers is to go slowly, do things in stages, and be conservative when making additions to wine that will dramatically change them. Adding acid, as it seems like you’ve found, is one of those things that will change many aspects of a wine, including taste balance, perceived tartness, color, pH, and microbial stability. Unlike Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Grigio, Viognier tends to live in the “rounder” side of life for a white wine, a bit more like a Chardonnay than a higher-acid zinger. I think a 3.66 pH is probably right on the edge of stylistically too high . . . but I’d be careful of taking it down too far. If you can measure pH while you do your trials, I’d shoot for a pH around 3.50.

I’m glad that you’re aware that a high-pH wine is more susceptible to microbial spoilage and that acid can help a wine age gracefully. Just a little bit can go a long way, however. I would counsel you to try a much smaller dose, like a reduction on the order of ten, and try adding 0.2 g/100 mL to your bench trial and see if you like the taste. I would wager that just that little bit, which would raise your TA to 0.644 g/100 mL, might lower your pH down somewhere in the realm of 3.50–3.55, which is fine for long-term aging of a rounded style, malolactic-complete Viognier as long as you keep your free SO2 levels around 30 ppm. If you like a little bit more of a zingy style, also trial 0.3 g/100 mL or 0.4 g/100 mL, but always taste afterwards.

I wouldn’t count on the acid dissipating much. Since your malolactic fermentation is complete, the acid levels will be pretty stable. The only way you’re going to lose acid now is if you have some solid tartrate crystals fall out of solution, which will probably just move the TA by 0.02–0.05 g/100 mL, if that. I’ve never seen huge TA or pH shifts due to tartrate fallout during aging. That’s the beauty and the risk of adding tartaric after MLF is complete — once you add it, it’ll stick around, which is why you’ve got to be careful not to add too much and be stuck with a terribly tart wine forever.