Lowering pH, add body to to country wines, degree days, & chitosan

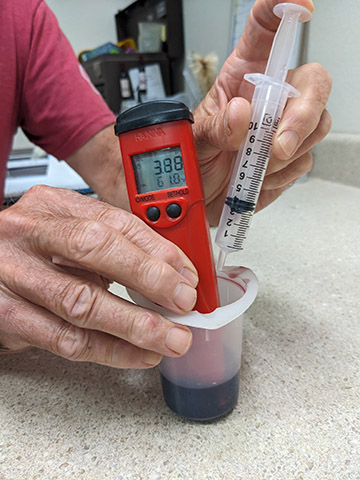

Q. I have just purchased California grapes (white: Chenin Blanc, Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, and red: Sangiovese and Cabernet Sauvignon). The pH for those is between 3.7–3.9 and titratable acidity (TA) is 3–4. I learned that pH for whites should be around 3.3 and reds around 3.5. Should I try to lower pH? When during the winemaking process and what method should I use to do this?

Pauline Schively,

Bechtelsville, Pennsylvania

A. The pH of these grapes do seem high. For California grapes, I like to see whites in the 3.30–3.45 range and reds in the 3.45–3.65 range when picked. However, many of our winemaking friends live in colder climates and/or make wine styles where they may want to maintain more acidity, which is why I give a general white range of 3.10–3.45 and a red range of 3.40–3.65 in The Winemaker’s Answer Book.

Lower pH means more acid. In the case of, say, a sweet Idaho Riesling, a winemaker may want their pH to be lower than your California version, especially if they’re going to leave a lot of sugar in it to balance out that acid. That’s what acid levels are really all about — balancing flavor, style, and microbial safety. Remember that most spoilage bacteria are happier at a high pH, so once you get over 3.75 you’ll have to store wines with at least 30 ppm free SO2 and keep your containers scrupulously topped up.

I use tartaric acid powder to adjust acidity in reds. For whites I’ll sometimes do an acid blend of 2⁄3 tartaric and 1⁄3 malic acid if I’m not going to take them through malolactic fermentation (MLF). I find that malic acid adds a little apple-like “zing” to white or rosé wines. Simply weigh out the number of grams of acid you want to add (a small digital scale is an invaluable tool) and dissolve the acid in just enough water to liquefy the crystals. Add to your juice or must, mix well, and you’re good to go. Acidity should always be adjusted before pitching the yeast as anything you do to drastically change the yeast cell’s environment can make them prone to spitting out stinky hydrogen sulfide or even stick mid-ferment.

How much acid you’ll have to add to get to where you want is a bit of a trickier question. pH is a non-linear measurement and, especially since wine is a “buffered” solution, it’s hard to predict how a certain g/L acid addition will shift your pH. Even pros have a tough time dealing with this — often all we can do is go on our experience with the vineyard and make more than one addition to try to not overshoot our pH goal.

You’ll have an easier time, however, if you can get your musts measured for total acidity in g/L or g/100 mL. Commercial wine labs can help with analysis. Once you have your g/L number, you know if you add a certain amount of g/L you’ll adjust your TA accordingly. I like my California whites between 5.5–8.0 g/L and reds between 5.0–6.5 g/L, though it’s always a decision based on taste and balance of richness, flavor, and other factors. Don’t add too much acid, however, if you want your wine to go through MLF. Most ML bacteria have a hard time going through fermentation if the pH is below 3.30.

Q. Over the past year, I have made about ten different fruit and berry wines. For most of them, I have followed Jack Keller’s recipes, both from your site and his book, and the wines have turned out well! However, a consistent issue with all these wines is that they have become a bit too thin. Country wine recipes are almost always diluted with water. From my limited knowledge, I understand that this is mainly due to the high titratable acidity (TA) values of the fruits and berries. At the same time, I imagine that a grape winemaker would probably not think it obvious to dilute grape must (and the same likely applies to a cidermaker) to adjust TA values. I imagine instead that in such cases, one might try to blend different grape musts or find other solutions? This has me reconsidering the recipes I have used, and I would like to hear your thoughts. Are there alternatives to water that might work better? Mixtures of berries, fruits, and root vegetables that together could work instead? Or is water the only option?

Lars Soderlind

Stockholm, Sweden

A. You are really onto something here! Water is added to recipes for many different reasons. If you’re making a wine with flowers or dry fruits (like dandelion wine or elderberry wine) you’ll definitely need to add some liquid to simply have enough volume to ferment and for the flavors to be dissolved and distributed. However, using a lot of water in recipes of any kind risks a dilution of flavors, sugars, acids . . . everything! Making fruit and “country” wines can be tricky to dial in. You want the flavors, colors, and aromas of your primary material, but you also need enough sugar, acid, and sometimes tannin to get a balanced product at the end. I think your solution is simple: Grape concentrate needs to be part of your must and juice-adjustment arsenal.

Not only does grape concentrate (and you can buy all sorts of varieties to complement your other fruits and roots) contribute the aforementioned components, it also importantly provides yeast nutrition as well as mouthfeel and finish precursors to fermentations. Instead of adding just water and granulated sugar to recipes, try adding a solution of grape concentrate, adjusted to the correct initial Brix needed for your recipe, instead. Since it already contains acid, you may need to add fewer acid powders than are called for in the recipe or in the case of very high acid components you may even need to tweak the acidity down by adding potassium bicarbonate. Cabernet and elderberry is a classic combination, as are Chardonnay and dandelion — the sky’s the limit!

Q. Is there any wine grape that can be successfully grown in an area with a heat summation of 1,200. I am near the Pacific Coast (just inland from Bodega Bay, California) and summers are not very warm, typical 70s °F (low-mid 20s °C), sometimes in the 80s °F (upper 20s °C), but always cool at night. Do you think Gewürztraminer or Pinot Noir may be able to grow here?

Marcella Roberts

Valley Ford, California

A. Interestingly, even though your heat summation units are low, you are close to the Pacific Coast so I am guessing your winters are mild. European grapevines (Vitis vinifera) grow at a minimum of 50 °F (10 °C) and winter kill at around 0 °F (-18 °C), so during the growing season, during the day, your temperatures should do quite nicely.

The “Winkler Scale” or “UC-Davis Heat Summation Scale,” which measures what are dubbed “degree days,” is only a rough guide to which varieties will thrive in which areas and is solely based on temperature. Basically, it looks at the temperature during the growing season (April 1 to October 31), which roughly brackets bud break to harvest in most areas of the Northern Hemisphere. The number of “degree days” is equal to the average daily temperature in degrees Fahrenheit minus 50 during that period. According to the following scale from UC-Davis, the ranges are divided into “regions” with the accompanying recommended grape varietals:

Region I: Below 2,500 degree days; Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Gewürztraminer, Riesling

Region II: 2,500–3,000 degree days; Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sauvignon Blanc

Region III: 3,000–3,500 degree days; Zinfandel, Barbera, Gamay

Region IV: 3,500–4,000 degree days; Malvasia, Thompson Seedless

Region V: Over 4,000 degree days; Thompson Seedless, other table grape

As you can see, your 1,200 degree days is Region I or below (is that a “Region 0”?) and so Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Gewürztraminer, and Riesling are the vinifera varieties that you would probably have the most luck with.

As I said earlier, however, this scale only takes temperature into account and certainly not slope, aspect, microclimate, weather, precipitation, pest species in an area, trellising, or soil composition. As you can see, there are a myriad of things that can influence the success (or not) of a particular grapevine species. For example, I’m from a little surf town south of Santa Barbara called Carpinteria. If you look at its heat summation units, I should be able to do well with Region I fruit — like you, summer days are typically in the high 70s or low 80s (mid-upper 20s °C). However, Pierce’s Disease, brought on by the glassy wing sharpshooter insect, is a major deterrent to successful vineyards in the area. That and the fact that it doesn’t get very cold at night really means that Carpinteria does best with what it’s most famous for: Citrus, avocados, and flowers.

I would talk to your local university extension, county extension, or farm bureau folks. Likewise, take a cue from what other farmers in your area have planted and see what you think you could do. In the last decade or so, there has been a “Far West” viticultural movement in your area. The West Sonoma Coast Vintners is a local group dedicated to the promotion of vineyards and wineries on the far western edge of Sonoma County where, as you mention, even though it may not all be directly on the coast is far, far cooler than the hotter, inland parts of the county that parallel the Highway 101 corridor. Get connected with those folks to get some ideas about what types of grapes and farming practices they’re finding successful. However, always remember that your property may not be at all like that of your neighbors. Take into account aspect, slope, and site-specific challenges. If you need to maximize the heat that you do have, try planting vines on a south-facing slope or a spot that is sheltered from big ocean breezes that may stress vines too much. If all else fails, try some Vitis vinifera hybrids like Marquette or Traminette that are tailor-made for cooler areas.

Q. I use chitosan and kieselsol for clarifying agents in my wines. Because Chitosan is made from shellfish byproducts, I am curious whether it may cause an allergic reaction (headaches?) to those who are allergic to shrimp or lobster?

Roy Melville

Bisbee, Arizona

A. Though I’m no medical doctor (and certainly don’t play one on TV), from what research I was able to pull together, if I personally had a shellfish allergy I would feel comfortable using chitosan products to clarify my wine. I will let you make up your own mind (in conference with your physician, of course), but from what I understand, seafood allergies derive from proteins in crustaceans and shellfish, not from materials in their shells. Chitosan is a manufactured product that (in some cases) is derived from chitin in the shells, a natural polymer. During the manufacturing process, the shells only (no fleshy protein bits) are used, and any protein that could possibly be clinging is removed. Most winemaking supply houses (AEB, to name one) these days are producing chitosan from Aspergillus niger, a fungus, so there is no seafood involved.

Chitosan is a great flocculating agent in wines. It precipitates solids and is a very efficient clearing agent — basically you add it to your wine, it gloms on to solids, and then falls out of solution to the bottom of your container. If you rack cleanly enough (giving the solids plenty of time to settle) you should be able to leave the chitosan fining agent behind in your container, along with the tannins and wine proteins it pulled out. It also is an important antiseptic agent and can inhibit microbiological activity, helping to prevent volatile acidity (VA) formation as well as in stopping unwanted fermentations. Because of this, it’s not wise to use it right before you might want a wine to go through malolactic fermentation. It can be very useful in preventing Brettanomyces for wine stored in wood.

I think chitosan is an under-utilized winemaking ingredient that more home winemakers should become accustomed to using.