Barrel Fermentations

Oak barrels have been an important part of the winemaker’s tool kit for more than 2,000 years. Maturing a red wine in oak barrels will soften tannins, stabilize color, and add a toasty/oaky character that complements varietal flavor from the vine. Although tannins and color are not a concern when making a white wine, they too will benefit by picking up oak flavor and aroma from aging in barrels. Typically, barrel-aging begins after alcoholic fermentation is complete and a white wine is racked out of its fermenter, or in the case of a red, pressed off its skins. However, you do not have to wait until your wine is dry to start getting the benefits of oak. You can also use oak barrels for fermentation of white wines or with some extra effort, you can even ferment your reds in barrels.

Getting You Barrel-Ready for Harvest

A standard-sized barrel of 59 gallons (225 liters) is an excellent choice for barrel fermentation, but smaller barrels will work as well. Just remember that a smaller barrel has a greater ratio of surface area-to-volume, so it picks up oak and oxygen more quickly. Before you use a barrel for fermentation, you need to make sure that it is ready to receive wine. Barrels can dry out when stored empty, causing the staves to shrink and leading to leaks when it is filled. In this case, the barrel can be recovered for use by soaking it with water, making the staves expand and tighten. Also, empty barrels that have been used previously to store wine can become “sour” from bacteria and smell like vinegar if they have not had sulfur wicks burned in them frequently enough. If this happens it can be treated with SO2 and citric acid. For more on maintaining a barrel, check out “Barrel Care Techniques” at www.winemakermag.com/technique/barrel-care

Barrel Fermentation for White Wines

Fermenting a white wine in an oak barrel affects the wine in several ways. First of all, barrel fermentations tend to start and proceed a little more rapidly. This is due in part to the fact that conditions are often a little warmer since the wood tends to hold in the heat produced by fermentation more than either a glass carboy or stainless steel fermenter would. In my experience, barrel ferments usually go dry a few days before the same wine fermenting nearby in a carboy. The downside is that a warmer fermentation will reduce the fruitiness of the wine a bit. On the plus side, the wine often takes on a pleasant toasty aroma and will finish alcoholic and malolactic fermentation (MLF) more readily.

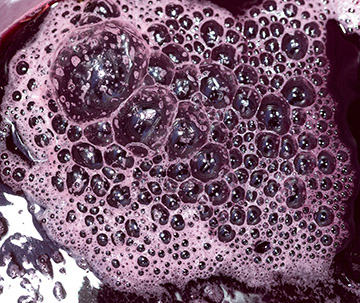

Another consequence of a vigorous fermentation is that it will have more foam and you will only be able to fill the barrel to 85–90% of capacity. Low-foaming yeasts like Prise de Mousse (EC-1118) or Bourgoblanc (CY3079) both are good choices to prevent the mess of a barrel foaming over. For venting CO2 during fermentation, a standard bubbler-style airlock or a silicone “breathing” bung will allow gas to escape but prevent air from entering the headspace. After alcoholic fermentation is complete, the barrel should be topped up to prevent oxygen pick-up.

One big advantage of fermenting a white wine in barrels is the ability to do sur lie aging (aging on the lees). Post-fermentation lees are primarily dead yeast and with extended contact the yeast undergoes an enzymatic breakdown or autolysis that will give the wine more viscosity and a creamy-yeasty character. This character can be intensified by bâttonage (stirring) the lees periodically. Stirring every 2–3 weeks followed by topping is about right to get the best effect. Another advantage is the yeast lees will help protect the wine from oxidation.

Yeast autolysis will also release nutrients that will encourage the growth of malolactic bacteria. SO2 can be added and the acidity adjusted after MLF is complete. The wine can then continue to be left on the lees until aging is complete. If you do not want your wine to undergo MLF, SO2 should be added when the wine is dry to prevent spontaneous growth of malolactic bacteria. There is one caveat to sur lie aging: If the wine has any off-aromas like sulfides, it is best to get it off the lees as quickly as you can.

Chardonnay is the classic example of a barrel-fermented and sur lie-aged wine where the toasty-yeasty aroma and rich creamy texture is quite complementary to its varietal character. However, these flavors are not the best fit for a wine with a fruity/crisp profile like Sauvignon Blanc or Muscat. If you would still like to do a barrel fermentation for your white wines but would like to diminish the sensory affects you can use a neutral barrel and then rack the wine off the lees after fermentation is complete.

Barrel Fermentation for Red Wines

At first, fermenting a red wine in barrels seems like an impossibility since red wines must ferment on the skins and there is no way to get them in (much less out) through the bung hole. However, there are a few ways to barrel ferment red wines, one that is simple and two that are a bit more advanced. But before we go into how to do it, let’s cover why you might want to give your red wine a little oak contact while it is still fermenting.

Traditional barrel aging for reds takes place after fermentation is complete and has three primary effects on the wine: 1) The wine becomes more concentrated due to evaporation through the wood. 2) The wine is slowly exposed to oxygen to soften the wine by aiding the polymerization of the tannins. 3) The wine extracts flavor and aroma components from the wood. Aging of wine is a slow process, therefore in the relatively brief time of fermentation you will not see a lot of impact from concentration or oxygen exposure.

When fermenting a red wine in a barrel you will still pick up aromatic components that can give the wine an oaky/toasty character during fermentation. Additionally, red wines that have oak contact during fermentation will have less of a vegetative aroma by a reduction in pyrazines. Many winemakers also attribute oak contact during fermentation to an increase in color due to co-pigmentation. This is where color compounds (anthocyanins) from the skins combine with other tannins extracted from the wood or other sources to stabilize the color. Although, the scientific literature supports that this effect is more pronounced with tannins extracted from the skins and seeds rather than the oak of the barrel.

The first and simplest way to use barrels for red fermentation is to press the wine early, when it is at about 5 °Brix, and let the yeast finish their work in the barrel. This eliminates the issue of trying to get the must (skins, pulp, seeds, and juice) in and out of the barrel through the bung hole but will only give you a partial effect of a full fermentation. Letting a young red finish its fermentation in the barrel will also allow you to do sur lie aging. The effects are similar to those when it is done on a white wine — better body and mouthfeel, protection form oxidation, and enhanced MLF. Sur lie works particularly well with medium-bodied reds like Pinot Noir.

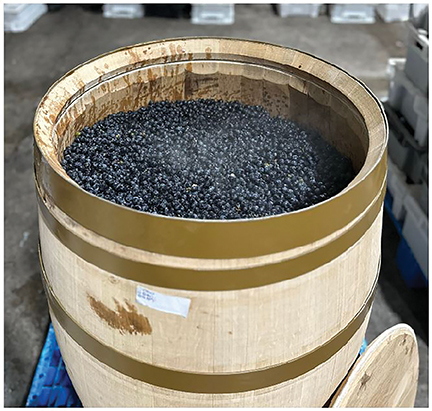

Another option is to loosen the hoops at one end of the barrel and remove the head. The hoops are then retightened and the barrel is placed on its end and used as an open-top fermentation tank. The sturdiness of a barrel with an open top makes it an excellent fermentation vessel. If your crusher/destemmer is small enough you can place it on top of the open end of the barrel and process your fruit directly inside for fermentation. Two open-topped barrels filled to fermentation capacity will result in about one barrel worth of wine once it is pressed.

The third technique of fermenting a red wine in a barrel involves some more advanced coopering skills. In this case, the head is removed as in the previous method, the barrel is filled with crushed grapes, and then the head is reinstalled so the barrel can be placed on its side. The barrel can then be “punched down” just by rolling the barrel side to side to mix the skins and the juice. This method is also a great way to do an extended maceration where the young wine is left on the skins for several weeks after fermentation is complete. Simply top up the barrel with wine after it is dry and let it sit until you are ready to press.

Reinstalling a head so the barrel does not leak is tricky so I would not recommend trying it unless you are skilled with coopering or if you have an older barrel that has reached the end of its life, so you do not have much to lose if you do not get it right. If you are using the open-top procedure to ferment and then reinstalling the head for dry storage it is not so critical to have a leak-proof seal. When I used this method for home winemaking, I did not want to deal with taking the head off and on every year, so I made a replacement covering for storing the barrel on end. This was simply a round piece of plywood with a bung-sized hole in the middle that I could use when burning a sulfur wick.

Non-Barrel Options for Oak

If the idea of using oak during fermentation intrigues you but you are a little intimidated by the complexity of adding barrels to you cellar, you can always start by using an oak alternative. These are non-barrel oak products such as toasted oak chips, cubes, staves, or other forms that you can add to a white or red wine during fermentation. These allow you to get some of the benefits of oak even if your fermentation container is made of stainless steel, glass, or plastic. There are lots of options here as to type of oak, toast level, and amount to add. For white wines, French or Hungarian oak usually has the best flavor; however, for red wines a blend of French and American oak is a good option. I usually add 1–3 ounces per 5 gallons (25–75 g/20 L) of a medium or medium-plus oak for fermentation. I recommend being conservative to start, remember you can always add more oak later in the process, but you cannot add less once you have put it in the wine.

Conclusion

Using barrels for fermentation is a great way to step up your winemaking game. To get the best results, you might need to learn some new skills on coopering and working with barrels, but it allows you to make whites that have more body and flavor and reds with more complexity and color. It might even make harvest a bit easier since a standard barrel holds 12 times as much volume as a carboy. The larger volume means that you will have fewer containers that need daily Brix readings and punchdowns during harvest. On the whole, most winemakers who give barrel fermentation a try tend to stick with it because they are happy with what it does for their wine.