MLF: Tips from the Pros

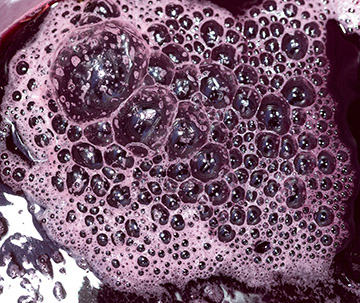

Some winemakers conduct malolactic fermentations during active primary fermentations, while others wait for primary to complete before pitching malolactic bacteria. Both approaches have their own benefits, and we asked two winemakers who fall on opposite sides of the debate for their insight.

Patrick Newton is the Winemaker at Mudbrick Vineyard, on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island.

I have been using Enoferm AlphaTM malolactic bacteria for the last 15 years as I have found it to work quickly and doesn’t impart too many other flavors in my wines. My goal is to make terroir-driven wines, so using a neutral malolactic bacteria that is strong allows me to get the fermentation over quickly so the reds can be cooled down to 54 °F (12 °C) for their aging. I do this primarily for the reduced chances for Brettanomyces growth in the wines. If there is one thing that tastes the same everywhere in the world, it’s Brett. Nothing destroys terroir more than Brett.

All of our reds go through malolactic fermentation (MLF), as well as some of our whites, which I put through MLF for different reasons: I harvest Chardonnay at low Brix levels (20.5–21.5) with a titratable acidity (TA) between 9-11 g/L. This way I get a relatively low alcohol, but it needs to go through MLF to provide texture for mouthfeel. Our Albariño always comes in with very high Brix and searing acidity. I’m using MLF to knock some of this acid out and give the wine texture. The Viognier doesn’t have much acid, but I want to make a style like Guigal La Doriane — full malo, new oak, etc. It’s a very big wine!

For all the whites I incorporate lees stirring at specific times during and after malo, but more specifically around sulfiting. I don’t want any of those MLF buttery notes coming into any of the wines so I will continue to stir the wines for three weeks after sulfiting (using CO2 cover). This pretty much stops any MLF notes from coming through.

All of our wines that go through MLF will be inoculated two to four days after the natural primary fermentation has started. I do this so the MLF bacteria can build a population using the heat generated by the fermentation. I’m hoping MLF is well under way by the time primary fermentation is complete. Once again, I am doing this to reduce the time the wine is left warm, which in turn reduces the chances of bad yeast and bacteria infecting the wines.

Reds are in the fermenter 2–3 weeks and MLF is usually complete a week after the last of the reds are pressed and run to barrel, which is when we do the first check, though I suspect it’s probably complete even earlier.

My assistant winemaker is currently doing a trial of spring malo on some Chardonnay barrels. I have seen good results in the past but there is always a risk of aldehydes and volatile acidity (VA) development in the wine. These wines are kept at 54 °F (12 °C) through winter and topped weekly, and in our spring months we’ll warm the barrels up and inoculate.

For the reds, I have done sequential MLF for Syrah with good results (better color and texture), but I have not trialed any Bordeaux varieties. It’s quite a warm climate on Waiheke Island and the soils are clay. I don’t add acid to any of the juices/wine and it’s quite normal to have pHs of 3.8 (I’ve even had a 4 before). Brett loves a high-pH wine to grow in, so I don’t want to run the risk with the reds.

For home winemakers, be comfortable in what you do. Once you do the trials and have found something that works, stick with it. You don’t need to reinvent the wheel every time to make a new wine.

Jared Burns is the Winemaker and Founder of Revelry Vintners in Walla Walla, Washington.

We rely on a couple different commercial strains of malolactic (ML) bacteria as we appreciate the ability to control the timing and vigor of our malolactic ferments. We used to pitch our ML bacteria when primary fermentations were very low as measured at the fermenter. We moved away from this approach many years ago, as there is often a great amount of variability in the accuracy of measuring Brix at the fermenter. We found that, instead, getting consistently dry readings in barrel over multiple readings gave us better data, and reduced competition in primary and malolactic ferments.

All of our red wines go through MLF. We typically add 30 ppm of SO2 to all fermenters on the crush pad. That is the only SO2 dose given to each lot until MLF is complete. After pressing off red lots, we will begin to monitor Brix in barrel with a density meter. Once we get three readings that show the lot is dry for primary fermentation, we then go ahead and pitch ML bacteria (we haven’t found a need to add any malolactic nutrients along with the bacteria). We typically keep our barrel rooms around 68 °F (20 °C) until MLF is finished.

Within our program, we have one white wine that also goes through complete MLF. This is a single-vineyard Chardonnay that has qualities reminiscent of Burgundy, and the MLF really adds to the mouthfeel greatly. We use a strain of bacteria that does not produce diacetyl as we don’t desire the buttery qualities in this particular wine.

Because we have experience doing both sequential and co-fermentation approaches, and have come to feel more confident in the sequential approach, we haven’t found a need to revert back to co-fermenting. The only instance I would entertain such a maneuver would be in the case of a prolonged extended maceration in fermenter after the cap has fallen. That said, we don’t often do such extended macerations within our program.