Volatile Acidity Fixes

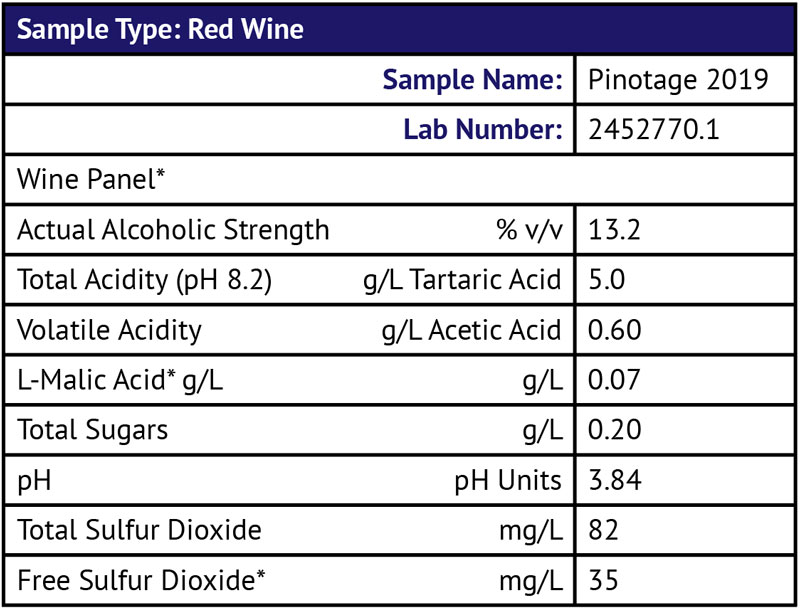

Q: Because of travel restrictions over the past few months, I was unable to rack my 2019 (New Zealand) Pinotage from a Speidel plastic fermenter to the stainless container or adequately manage sulfite levels (basically I was unable to travel back from the U.S. to New Zealand until recently). I could taste volatile acidity (VA) and sent the wine off for testing.

I have read that the legal threshold for VA is 0.7 g/L and blending is the best solution. So far, I have added another 1 g/L of tartaric acid and bumped up the sulfite to 75 ppm. Unfortunately, I don’t have any blending wine. It is OK to drink, especially with food, so I am reluctant to dump it. Do you have any suggestions? I don’t normally filter my wines — should I pass through a sterile filter before bottling, any other way to reduce the VA or minimize the sensory impact and can I prevent it deteriorating further?

— Mary Rogan • Auckland, New Zealand

A: Sadly, blending VA levels downward remains the only option available for reducing VA content in small lots. Larger commercial wineries, with big lots and bigger pocketbooks, can afford the expense of reverse osmosis and distillation technology to remove it from their wines but there’s no affordable option for small producers. Simple filtration doesn’t work to remove VA, though sterile filtration can certainly remove the spoilage yeast and bacteria that may be contributing to it.

The good news for you is that your VA levels are nowhere near approaching legal limits. The legal limit for VA in the U.S. is actually 1.1 g/L for white wines, and 1.2 g/L for red wines. At these levels, I indeed do find the wine objectionable. Sensorially, at 0.6 g/L, you should be within a tolerable range, especially for a wine that is already a year old. VA tends to climb with time and even though you had a moment during the wine’s lifetime where you weren’t able to keep the SO2 levels up in ideal ranges, it’s actually not that bad. It is possible, however, that you’re also smelling some aldehydes or acetaldehyde, which can smell like nail polish remover or paint thinners. If that’s the case, your SO2 addition should help bind up some of these and reduce the perception of those offensive aromas.

At a free SO2 of 35 ppm and a total SO2 of 82 ppm, I wouldn’t worry about the wine being safe to consume; it certainly is. Many wines are bottled with free SO2 in that range and though I’d certainly be wary of big additions in the future, your big add should tide you over for at least a couple of months as long as the wine isn’t exposed to oxygen and isn’t carrying a high microbial load. If you do suspect you’ve got spoilage bacteria (if you have any film yeasts growing, or if the wine is cloudy and spritzy where it should be clear and settled), you might want to filter it anyways.

I’m glad that you added some tartaric acid to get your pH down — that’ll help prevent some of the inevitable future VA creep. (For other reader’s reference, it always helps me diagnose a problem when I can see a wine’s analysis; it gives a bigger picture, so thank you very much for including yours!) High pHs, especially coupled with oxygen exposure and low SO2, are notorious for leading you down the path to VA issues. Indeed, VA prevention is something about which an entire book can be written. Just give a search on our homepage, winemakermag.com, for some great free articles and member’s-only content. VA is definitely something where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

For your wine, in your case, I’d say that if you like how the wine tastes, feel free to keep it as topped as possible, with your free SO2 levels up between 25–30 ppm, and see how it ages over the next month. I know it sounds a little blasphemous but, in the past, I have told readers (if they don’t feel like it’s breaking all the rules) that it’s OK to buy some wine to blend if it helps rescue a batch. Just be sure to tell your friends and family full disclosure that it’s not all yours . . . if it turns out tasty!