Lowering pH

Q: I have just purchased California grapes (white: Chenin Blanc, Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, and red: Sangiovese and Cabernet Sauvignon). The pH for those is between 3.7–3.9 and titratable acidity (TA) is 3–4. I learned that pH for whites should be around 3.3 and reds around 3.5. Should I try to lower pH? When during the winemaking process and what method should I use to do this?

— Pauline Schively • Bechtelsville, Pennsylvania

A: The pH of these grapes do seem high. For California grapes, I like to see whites in the 3.30–3.45 range and reds in the 3.45–3.65 range when picked. However, many of our winemaking friends live in colder climates and/or make wine styles where they may want to maintain more acidity, which is why I give a general white range of 3.10–3.45 and a red range of 3.40–3.65 in The Winemaker’s Answer Book.

Lower pH means more acid. In the case of, say, a sweet Idaho Riesling, a winemaker may want their pH to be lower than your California version, especially if they’re going to leave a lot of sugar in it to balance out that acid. That’s what acid levels are really all about — balancing flavor, style, and microbial safety. Remember that most spoilage bacteria are happier at a high pH, so once you get over 3.75 you’ll have to store wines with at least 30 ppm free SO2 and keep your containers scrupulously topped up.

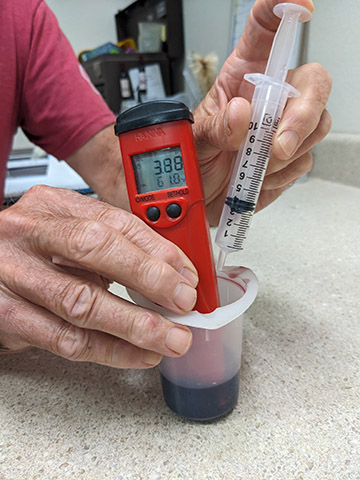

I use tartaric acid powder to adjust acidity in reds. For whites I’ll sometimes do an acid blend of 2⁄3 tartaric and 1⁄3 malic acid if I’m not going to take them through malolactic fermentation (MLF). I find that malic acid adds a little apple-like “zing” to white or rosé wines. Simply weigh out the number of grams of acid you want to add (a small digital scale is an invaluable tool) and dissolve the acid in just enough water to liquefy the crystals. Add to your juice or must, mix well, and you’re good to go.

Acidity should always be adjusted before pitching the yeast as anything you do to drastically change the yeast cell’s environment can make them prone to spitting out stinky hydrogen sulfide or even stick mid-ferment.

How much acid you’ll have to add to get to where you want is a bit of a trickier question. pH is a non-linear measurement and, especially since wine is a “buffered” solution, it’s hard to predict how a certain g/L acid addition will shift your pH. Even pros have a tough time dealing with this — often all we can do is go on our experience with the vineyard and make more than one addition to try to not overshoot our pH goal.

You’ll have an easier time, however, if you can get your musts measured for total acidity in g/L or g/100 mL. Commercial wine labs can help with analysis. Once you have your g/L number, you know if you add a certain amount of g/L you’ll adjust your TA accordingly. I like my California whites between 5.5–8.0 g/L and reds between 5.0–6.5 g/L, though it’s always a decision based on taste and balance of richness, flavor, and other factors. Don’t add too much acid, however, if you want your wine to go through MLF. Most ML bacteria have a hard time going through fermentation if the pH is below 3.30.