(Another) Year in the Vineyard Wine Blog by Wes Hagen, Week #17: Diversity and Darwin

Winemaker Magazine

(Another) Year in the Vineyard Wine Blog

Week #17: July 2nd-July 8th, 2010

The Theme is Diversity:

Genetics, Critters, Fog, Flavor, and Darwin

(amazingly described in the context of growing and making wine!)

What an odd job I have. In the last 24 hours I have driven to Los Angeles and helped set up a five course menu (and sold 5 cases of wine) for a wine dinner, researched the history of Ballard Canyon, communicated with a post-doctoral fellow at Cal Tech concerning a grape genome and a semi-secret yeast project we’re working on, had a crew meeting to finish fine tuning the canopy management of the Clos Pepe vineyard for the 2010 vintage, secured another part-time intern, set up cell phone extenders in both houses on the Clos Pepe compounds, sent out two separate email blasts concerning events and wine dinners coming up this Summer, managed Intern Tony taking samples of various clones of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay here at the Clos to see if different climate/soil conditions/frost patterns/salinity can change the genetic structure within and without a clone/cultivar of winegrapes, sniffed and tasted 94 barrels of 2009 Estate and Axis Mundi wines and did some S02 additions to the barrels that required them, got all barrels topped, cleaned and rinsed (with Tony’s help), and now in the next six hours I need to finish and publish this blog, roast coffee so I can wake up tomorrow, go to a Kung Fu class, head to a meeting of the Ballard Canyon Winegrowers AVA group to look at maps and update the locals on the project, and then end up in Lompoc at 7 pm for dinner at Hether and Errin Briggs’ house to discuss the possibility of opening a Clos Pepe Estate Wines Tasting Lounge at our winery in Lompoc. That last sentence likely qualifies as the longest in the two year history of this blog. And I may also mention that July is supposed to be the quiet before the storm of harvest, and not the storm itself. What could be considered a 14 hour work day contains a laundry list that most folks, taking one or two of the items in a day, would be a dream vacation. Getting to study the pinot noir genome? Tasting 94 barrels in a morning? Walking a vineyard? Not exactly a grindstone—but my nose is firmly against it and I love it that way.

I mention the busy nature of the last few days not for you to feel pity for me, but to encourage a touch of envy for the diversity of my task list for any given day. The theme for today’s blog is diversity. It’s rare that I have my days packed like this, but I found it an excellent example of how many different things I may do in any given week. Some are like ditch digging—sweaty field work, and others are more like grad-school research. Some are done with a wine glass in hand, some are done at table with food and customers and chefs. Sometimes I check email, sometimes I check on the chickens to make sure a hawk hasn’t stolen one away, and sometimes I try to scare a hawk away from my brother after it divebombed him on the golf course (true story). Diversity is good, and my life is enviable. Getting to do a hundred different things every month is far more enjoyable that sitting in a cubicle filling out the same paperwork every day, sneaking peeks at a computer screen to read some crazy bastard’s vineyard blog. If this blog is a window out of a dreary, corporate sweatshop, then I salute you for keeping the cogs of American business greased with ink and doldrums. I’ll do my best to keep it light, interesting and obligingly clever and educational. And if you could buy a bottle or two every few months, we’ll keep this business and blog running—your window to an agrarian life Windexed and streak-free.

The Diversity of Weather: Fog retreats to sea/Stumbling on its heels, ocean/Breathes sun, exhales mist.

The vineyard is is a beautiful, slow-maturing stasis. The weather hasn’t topped 73 degrees in the last month, and we’ve been socked in with fog every day from 6 pm until (usually) around 2 pm. As you can see from the pictures of the clusters and canopy from the last month, there hasn’t been much evolution in cluster size…I’ve been saying the bunches will close for weeks, and they are finally just about closed up. It’s been one of the coolest beginnings of Summer I can remember, even for Lompoc, and it appears we’ll still be enjoying this cool pattern for another week or so before things go back to a normal mind-to-high 70’s pattern that’s normal for this year. The cool weather and strong low-pressure/fog combo is extending the growing season. Even though California gets a reputation for biog fruit bombs that lack a sense of vintage variation, I find that the Santa Rita Hills puts an inimitable vintage stamp on each of its wines. Sure we have plenty of sunshine, fog, wind and cool temperatures, but the diversity within our seasonal patterns surely changes the wines’ style and structure every year. Blueberry, blackberry, cherry, baking spices, sagey underbrush—all of these can be considered the typical aroma/flavor profile, but each vineyard and each vintage provides a different balance and attunement. In a cool year like 2006 or 2008 we may get a touch more spice and herbaceousness, in a hot year like 2004 we get more cherry and alcohol in the nose. In a perfect year like 2007 all aromas and flavors are in perfect harmony and balance. Some vintages may age a little more gracefully (cool ones), some may be more generous in their youth (warm ones), and some may confound any generalization. Stylistically, pinot noir is as ephemeral and moody as a potentially beautiful 15 year old girl coming out of her awkward and lanky phase. She’s becoming a beautiful young woman, she knows people are noticing, but she may switch her temperament moment to moment between being cruel/judgemental and practicing her seductiveness. That’s pinot noir in a barrel. Always changing, always confounding, often frustrating, but sometimes dangerously alluring.

But I was speaking about the vineyard. (Long pause.) Maturity is only creeping along, which means hang time will likely be extended. I expect to see fruit starting to color up in the next month—but I wouldn’t be surprised if it were a week to ten days delayed as opposed to last year. This doesn’t necessarily mean that we’ll have a later harvest in 2010, but that could clearly be the case. Vintages in the Santa Rita Hills are always punctuated by hot weather…the Santa Ana Winds that reverse the on shore marine flow and get us into the 90’s for a few days at a time. In those weather events, ripeness (as measured in sugar content, or Brix) rises quickly, and we hope the cool periods have allowed the grapes enough hang time to match the sugar content with flavor.

Diversity of Harvest Chemistry and Winemaking:

Our picking schedule will also encourage diversity—we will pick some pinot noir fruit a bit earlier (maybe 23 Brix), a good deal around 24 degrees Brix, and then another small amount slightly riper. This way we get a beautiful blend of the entire vintage..the less ripe and more elegant acidity, the core of ripe, balanced fruit, and then a dollop of ripe richness—like a bit of whipped cream on top of a piece of blueberry pie. We’ll ferment each of 5-6 lots with 3-4 different yeasts to encourage as many fermentative flavors (diversity) as possible, and also use five to six different barrel makers (using three different French forests) to also encourage as much diverse oak flavor as a seasoning in the wine as it sits for a full year in elevage—or barrel aging.

Diversity in the vineyard and farming styles:

It’s very easy to fall into the trap of believing there are beneficial animals and pests in the vineyard, and that the pests should be slaughtered without quarter and the beneficial should be encouraged. The truth, at least in my head, is a bit more complicated. It’s more of a ballet than a battle. Ballet is usually a lot of coming together and pushing away. Seduction mixed with spurning, a representation of the difficulties of romance by watching dancers switch polarities like flip flopping magnets. The stage, in this extended viticultural metaphor, is the vineyard and the dancers are the critters. The most important element in viticulture is in keeping conflict, just like in any good ballet (lest the audience fall asleep). The good critters are being chased by the bad critters, and sometimes the good critters turn the table and do the chasing. The key, like in romance, is the chase. Because while bad critters are either chasing, or looking over their shoulder for a predator, they have little time to threaten the vines. This is the essence of diversity in a vineyard. Insects, mammals, birds, reptiles, even fish and amphibians are so busy engaging in survival that the vineyard remains relatively unscathed. The starlings are watching for the Cooper’s Hawk, the gophers and squirrels know the barn owl is never far off. The leafhoppers are stirred up by the tractor rolling by, and the cave swallows follow the tractor’s dust plume with full knowledge that a buggy meal is close behind. Gopher snakes eat the gophers and the king snake eats the gopher snake, and the red-tailed hawk eats the king snake, and so it goes and so it is supposed to go. A small population of pests is likely better than no pests at all. Pests attract their predators, and that keeps the niche space filled so no specific pest can take over the vineyard. Vive la difference!

Diversity of the Grapevine and the Magic Yeast that Makes Us Tipsy:

I can’t let too many cats out of the bag yet, but I have received clearance from my partner in crime and genetics, the mighty Paul Tarr, post-doc Fellow at Cal Tech in the Division of Biology, (Twitters as @bouchetfugacity) that I can start leaking out aspects of his grape genome project and aspects of the yeast project that we are working on. I say ‘we’ are working on, but I am really just a conceptual partner. He does all the lab work and the post-doc, Ph.D. kind of stuff that makes my Liberal Arts head spin. Without going into too much brain-numbing detail, Paul is studying environmental factors and how they impact genetic diversity within and without specific clones/cultivars of wine grapes. Clos Pepe is participating by providing grape berry samples at various levels of maturity for him to study. The first area/variety I chose to sample was our Wente Clone Chardonnay—which will be sampled from a protected hillside (sample 1) as well the vines that get frosted almost every year (sample 2) to see if the vines are adapting to a high frost-probability. I also chose two samples from our Estate 667 Pinot Noir—a sample from the balanced, healthy section and a section that struggles due to high salinity from soil and sea breezes. The third section is from our Pommard Clone..one sample from two different rootstocks. This is an interior section of the vineyard that has very standardized vigor, to see if the rootstock is influencing genetic mutation.

The second project we’re working on is still a bit more secretive, as the result may be as interesting commercially as it is scientifically. We plan to guide a yeast strain to a new genetic structure that will allow us to moderate and modify how much alcohol it produces. That’s about as much as I can tell you right now, but we may be able to do some real-life testing with some yeast strains in Harvest 2011 and report some findings. If we can make a clean-fermenting yeast that allows a longer hangtime, higher ripeness and lower alcohol conversion, I can’t describe how utterly revolutionary that could be to New World wines finding balance for food, table and the cellar. Truly exciting stuff.

Diversity of the 2009 wines:

You will rarely hear a winemaker discuss publically one of the greatest secrets of the cellar. That secret is this: there is rarely perfect flavor and structural consistency from barrel to barrel, even in the same fermentation lot, the same cooper and even the same yeast. Every barrel of wine in the cellar takes on a literal life of its own, and just as the microclimate of every vine’s fruiting zone changes the fruit, the microclimate of every barrel in the cellar impacts flavor and soundness. A barrel aged at 75 degrees will be vastly different than a barrel aged at 55 degrees. Barrels near a wall in the cellar will mature at a different pace than a barrel in the center of the cellar. Barrels at the top of a stack will be different than those on the bottom. This is one reason I like to keep all of my barrels single stacked on the winery floor. That’s the coolest area and it’s also very easy to pop a bung and get your nose in that barrel to assess its maturation. In the end, as long as each barrel is kept sound by careful tasting and lab work, the diversity of flavors becomes gestalt when the barrels are all blended into a single wine. Each of 40 barrels of 2009 Clos Pepe Estate Pinot Noir add their uniqueness to the sum of the final blend. Some are bright and fruity, some are brooding and earthy..some have a hint of stem character that wouldn’t be good by itself, but when less than 3% of the blend adds a charming complexity. Not surprisingly, the Chardonnays in barrel (either in stainless cask or neutral French barrique), are not as diverse in their character as they age. Chardonnay is a bit more predictable, although it’s still fascinating to taste the subtle differences from barrel to barrel. And even more confounding is that the stainless casks are usually more different from one to another than the oak. That’s because the stainless vessels are reductive by nature. It’s a closed system. That means the gasses and interesting aromas and volatile compounds have nowhere to ‘blow off’ like they would in porous oak, so they ‘reduce’ instead of disappear. This is another reason why our ‘Hommage to Chablis’ Chardonnay is such a unique creature in the world of California white wine, and perhaps why the geekiest of Sommeliers that I know think that our small-production Chardonnays are our flagship wines. Even as a self-avowed pinot noir specialist, that makes me very happy. But I have no idea why.

Like everything else, I’ll chalk it up to diversity.

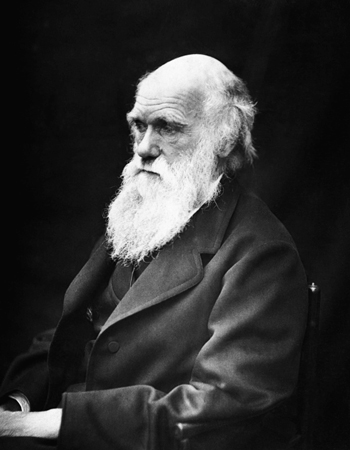

As a special bonus this week, I will also include this preamble of sorts for my next article in WineMaker Magazine. The article is about rootstocks, which I find to be a fairly uninteresting subject outside the insular professional viticultural community, so I looked for an angle that I could preface the subject with a good story. And boy did I find one. Thanks to Dr. Richard Smart for piquing my interest in Darwin’s contributions to grape growing, and to an article he published for Decanter Magazine that pointed my writer’s compass in the direction of Charles Darwin and his impact on rootstocks. If you want to read the whole article, you’ll have to subscribe to WineMaker Magazine, which I wholly endorse, as they subsidize this blog and my ongoing educational aspirations, and I’d prefer their checks to continue to clear!

How Darwin and Evolution Saved European Wine.

There was a time when grapevine vineyards were planted with only 18” cuttings from existing grapevines. A few buds went under the ground and few buds were left above the ground, and the vines would root on their own and a vineyard was basically free to plant if you knew someone you could secure some cuttings from. Since the discussion of choosing a rootstock can quickly become bogged down in very specific (and often boring) discussions of soil types, vigor and site specificity, let’s at least jazz up the subject slightly with a fun little historic journey back to the prehistory and the early scientific study of the grapevine.

Two hundred million years ago there was only one continent and, likely, only a few kinds of grapevines. While a single land mass dominated the face of the earth, the grapevine was evolving and changing slowly. When the continents separated (by 150 million years ago they were already taking the distinct shapes we recognize today), the grapevines began to adapt to the rapidly changing environments where they found themselves. To make a really, really long story short: grapevines generally evolved into three classifications: American vine varieties, Asian varieties and the European/Middle Eastern/North African family of vines that most of us use today for our wine production.

Charles Darwin spent many years studying the grapevine in his laboratory in Kent, England, and wrote that the vine was one of the most perfect examples of evolution in all of nature. In The Movement and Habits of Climbing Plants (1865), Darwin writes: ‘It is, also, an interesting fact that intermediate states between organs fitted for widely different functions, may be observed on the same individual plant of… the common vine; and these cases illustrate in a striking manner the principle of the gradual evolution of species.’ More specifically, a grapevine can produce a cluster or a tendril from the same node—which means a vine can assess its environment at any time during the early growing season and produce either fruit for reproduction, or a tendril to help the vine climb to a higher, sunnier spot where reproduction would likely be more successful. In human terms it’s like going to a singles bar and if the ladies don’t like what they see in you, you could morph into Brad Pitt for a better chance at procreation. That’s pretty darn cool!

Vines get love both in evolutionary and religious/mystic circles. Both Darwin and the Bible claim the vine for their own purposes: Darwin championed the vine’s penchant for adaptation, and of course wine is the official beverage of Christianity. Even the Bible says that when God flooded the earth, the one dude he chose to save was a viticulturist. When Noah waded off the ark, the first thing he did was to plant a vineyard and get his drink on. (I won’t mention the obvious questions: why he rescued and released a pair of gophers ,the European starling and the glassy-winged sharpshooter, and how he managed to produce an almost instant crop of grapes with a pair of every critter on earth slowly grazing their way away from the area.) Whether a Darwinist, a strict fundamentalist or neither, you have to admit that vines are amazingly prevalent in our history as human beings. Whether the Blood of Christ or just a simple drink after work, the history of wine and winegrowing is also the history of mankind, our religions , our science and our dining habits.

Starting in the late Paleolithic and throughout the Neolithic period, mankind began to dabble in collecting wild grapes and making wine. This process became more agricultural by the 4th Millennia BCE when it’s clear that Europeans living between the Black and Caspian Seas were domesticating grapevines in their villages and planting their first vineyards. Clearly the history of mankind growing grapes specifically for wine goes back at least 6,000 years and maybe as long ago as 10,000 years. We know that some of the first fired pottery shards that have been carbon dated to 6500 BCE show that wine was carried in these sealed pots—and if wine was being transported more than 8000 years ago, it’s easy to imagine that it was being made and experimented with for many generations previous.

Planting a home vineyard in this age was easy. It was all done with clippings off the last year’s vintage. Slips of dormant grapevine wood were kept moist in the Fall and Winter and planted in the ground before Spring warmed up. When the moist soil warmed, the dormant wood pushed roots out of the buds below the ground, and shoots on the buds in the sun. Voila! A new vineyard was just that easy. A few years later you would have a developed trunk system and a crop of fruit to make wine.

At this point we can fast forward past thousands of years of grape growing and the proliferation of vineyards throughout the ancient world. In fact, we can keep our camera lens focused on Charles Darwin, who continues to be the protagonist of our long and involved story of how rootstocks were invented and used. (Surprised yet?) England is both the culprit and the hero of this part of the story, which is an overarching theme of the Modernist Literature that emerged at the end of the 19th Century in England. British Botanists were busy collecting American plants—cataloguing and giving them all proper Latin names, when an insect escaped their laboratories and wreaked havoc on British vineyards, and then hopped the Channel to decimate the vineyards of Europe.

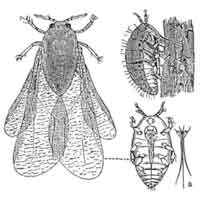

The bug, of course, was phylloxera—a root louse that has existed alongside American grapevines for Millennia. But when the insect had unrestricted access to the unprotected vineyards of Europe, the results were devastating. Within a few decades up to 90% of all European vineyards were destroyed by the single bug. The French did all they could to fight the scourge. But with only their provincial understanding of viticulture and without Darwin to help them, they tried methods that seem ludicrous to our modern, scientific minds: they buried a toad at the base of each vine ‘to draw the poison out’. It didn’t work. In the fifteen years between 1874 and 1889, wine production in France dropped by almost 70%. Hey, I would have started to bury toads too if I thought it would have helped.

So, how does Darwin come back into the story? Without the new idea that animals and plants adapt to their native environments and protect themselves from native pests, it is unlikely that any scientist would have been able to suggest the use of grafted American rootstocks for the rescue of European vineyards. Scientists primed by Darwin’s revolutionary work, such as Charles Riley and others, understood that American grapevines would have developed resistances to phylloxera over the millions of years they had been living in balance with the nasty American bug. And amazingly, vines that had been separated by hundreds of millions of years of geographic isolation were fused by grafting so that a European variety such as cabernet sauvignon could grow fruit on the grafted rootstock of an American vine variety. Only a few American varieties showed great promise in protecting grapes in phylloxera-ravaged areas. Vitis berlandieri, vitis riparia and vitis rupestris were the strongest three candidates, and most of our modern rootstocks are hybridized from these great native grapevine varieties. All three of these varieties can be found in Texas riverbeds, but v. riparia also can be found as far north as Quebec, and is cold hardy to minus 40 degrees.

So evolution saved the European Grapevine, and soon French, Spanish and Italian vineyards were replanted using American rootstock and began to produce a good crop once again. European vineyards are planted with U.S.-based rootstocks to this day, as a better solution has yet to be offered or proved. Such a fundamental shift in the way mankind viewed the natural world, the view espoused in Origin of Species, cannot be ignored in the history of winegrape production, and moving forward into the arena of suggesting rootstocks for your vineyard, let’s all take a moment to reflect and toast the man who changed the world and saved European wine, albeit indirectly: Charles Robert Darwin.