Better Together: Creating Red Blends

Early in my winemaking career I had the good fortune to work with one of the founders of Kenwood Vineyards, Mike Lee, who really knew how to blend wines to make them taste even better. Even though I was a rookie just out of school, he let me take part in blending trials tasting different vineyard lots to select which would make the cut for the final blend. If you are unfamiliar with the process of blending wine you may think that it is as simple as throwing everything together in one big tank and mixing it up, but to be successful you need to put a little more thought into it.

A winemaker would no more throw all their wines together without thinking than a chef making a soup would put all of the ingredients in the kitchen into one pot and call it done. To make something that actually tasted good a chef would carefully consider what might go well together, then once it was on the stove taste a spoonful out of the pot while it was cooking and add a little more seasoning based on what he or she thought would make it taste even better. Winemakers should approach blending in the same manner — taste the wine that they are working with and then ask themselves “what wines do I have that would make this blend perfect?”

What blending will do (and won’t do) for your wine

The goal of blending wine should be to add new flavors and create a wine that has more complexity and balance than the base wines from which it is made. In short, a wine where the whole is more than the sum of the parts. There are as many opinions to what makes a palatable wine as there are winemakers but most would agree a balanced wine with a myriad of complex flavors that go well together is going to be more enjoyable than a one-dimensional wine where one flavor dominates.

While blending can bring out the best in wines it cannot make a bad wine taste good. When an unpalatable wine is blended with something better you usually just end up with a bigger volume of mediocre wine.

Blending can make a good wine taste even better by compensating for any of its weaknesses such as to soften a wine that was too bitter or adding a little bit more youthful fruity aroma to a wine that has been well aged. There are many blending options available to accomplish these goals. You can blend wines from different varietals, vineyards, appellations, or vintages that may have very different flavors but are complementary to each other.

What to blend

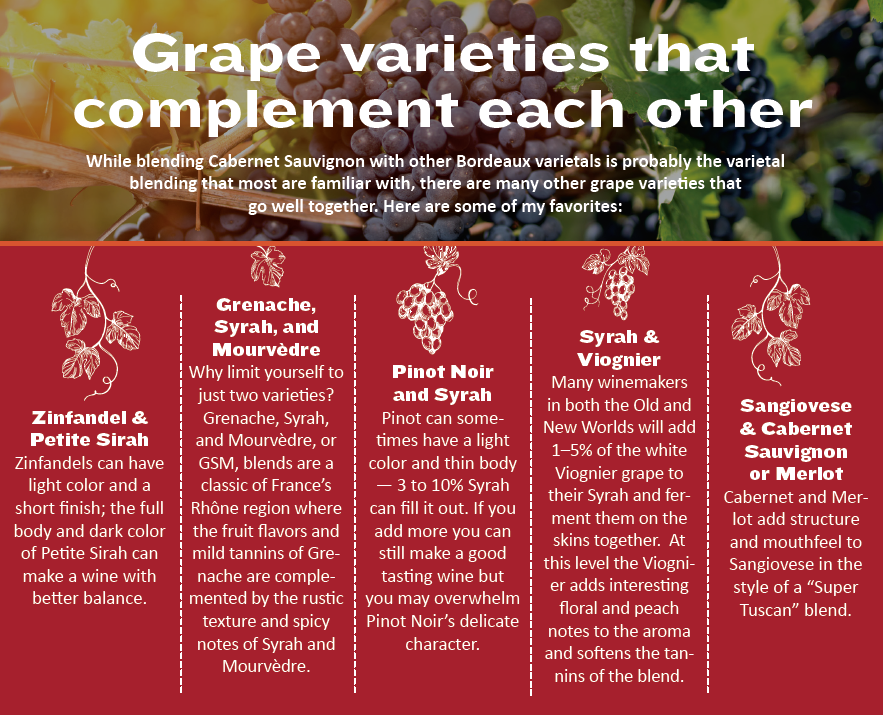

Cabernet Sauvignon is an excellent example of the potential of varietal blending. Cabernet Sauvignon is a late-ripening variety and in cooler appellations it might not get to the desired level of ripeness every vintage. Blending in a variety like Merlot, which ripens earlier than Cabernet and has a similar flavor profile, can be a lifesaver that adds ripe flavor to the blend in a cool year. There are a number of “Bordeaux” varieties that can offer a diverse palate of tastes to Cabernet Sauvignon. For me, I have found that Merlot provides ripe flavors with softer tannins, Malbec gives an abundance of fruit flavor, color, and body without being too astringent, Petit Verdot adds big tannins and ageability, while Cabernet Franc has an elegant flavor with a leaner body than Cabernet Sauvignon. You can think of adding a small percentage of these wines to fine-tune a Cabernet Sauvignon or you can use them in more equal proportions to make a red blend in the style of a Meritage.

Blending wines that have received different treatments is another option; such as a Cabernet Sauvignon that was aged separately in both French and American oak or combining two carboys of Marquette, each fermented with a different type of yeast. Blending a small amount of a younger wine into one that has just finished aging can be particularly useful. A full-bodied red may age for as long as two years and when it is racked out of the barrel it might have the smooth tannins and oak flavor that you were looking for but it may have lost most of its attractive fruity aromas that it had in its youth. In this case, adding 5 to 15 percent of the same wine from a younger vintage will bring back a lot of that lost fruity flavor and make a blend that has the best of both wines.

Blending is an area of winemaking where the home winemaker might be at an advantage to the pro. Commercial wines that are to be sold are bound by many state and federal regulations as to what is legal to put together. The rules vary a bit by state and region, but typically a wine must be composed of at least 75% of a varietal to be labeled as such on the bottle. For appellation it is 85% and for year of vintage it can be from 85 to 95%. The advantage to home winemakers is that they are only limited to what tastes the best to them. You can blend a wine that is 65% from one vintage and 35% from another year if that is what you like without worrying about the law or marketing.

Bench blends, the secret to success

While experience always helps, it is not really required to be successful at blending, you just need to make a trial blend, or bench blend, to taste before making the blend in the cellar. For a bench blend you assemble sample bottles of the wines that you are considering for the mix and combine a small amount of each in the same proportion that you would make in the cellar. Once the bench blend is made, taste it against the unblended wines and ask yourself “do I like this more or less than the original wines?” Why end there? Take it further and try different percentages of each wine, or just some of the wines you have available to you, to dial in the best blend.

This “try it before you buy it” approach is what makes blending wine such a powerful tool. Most decisions a vintner makes are based on conjecture. You may decide to pick your grapes at a particular level of sugar but you will never know for sure if the wine might have tasted a little better if the fruit had more hangtime on the vine. By making and tasting a trial blend before doing it in the cellar it allows you to try a number of blending options without consequences to find just the right one.

But how to select what wines to mix? First taste each wine that you may use and critically examine it for its strengths and weaknesses, writing down your impressions as you go. The wine that has the highest volume or the one with the best flavor profile that you are sure that you want to use for the blend is the base wine. Taste the base wine again and ask yourself “what does this need to improve the taste?”

As an example, if the base wine is a little too astringent, select a wine that has soft tannins that might complement the base wine. Make up a sample blend of the two wines; a good place to start might be 80% base wine with 20% of another wine. You will need a graduated cylinder and pipet to measure 80 mL of the base wine and 20 mL of the softer wine. Gently mix the new blend and taste it against the base wine and decide what you like best. If the new blend is now a little too soft, try again, this time adding 10% of the second wine to the base wine. Alternatively, if 20% of the second wine it is still a little too rough, try upping it to 30% and see if it is better.

Don’t get discouraged if it did not make the wine taste better — just try another combination. It is always a good idea to number the blend you are working on and write down the composition as well as any thoughts you have on the taste. When I was working at Kenwood it was not uncommon to be working with lots from 20 different vineyards and taste 10 to 15 trial blends before deciding on the final combination. Once I became a head winemaker the ultimate decision on the blend was mine, but I knew enough from my experience working with Mike Lee that you will get better results if you taste with others so you might want to ask your winemaking partners, fellow home vintners, or wine lovers to join you in the process if you can.

Keeping track of the math

In the earlier example we had a pretty simple 80/20 blend that can be measured in a 100 mL cylinder, but for more complex blends or to blend up a full bottle it might be easer to use a spreadsheet. If you have analysis or composition data for the wines you can also use the spreadsheet to see what the percentages for the blend would be. If you are proficient with Excel you can make a spreadsheet of your own. I am also sharing a blending template that I use, which you can download at winemakermag.com/article/pat-hendersons-blending-spreadsheet. Using this template, you can enter information about each wine you have available to you and amounts that you want to try for a blend and it will automatically calculate the small sample amounts needed to conduct a bench trial.

When is the best time to blend?

There are a number of options as to when in the winemaking process to blend things together and they each have their advantages and disadvantages. Some winemakers actually make field blends where grapes of different varieties are crushed and fermented together. Out here in California’s Sonoma Valley you often see this in old vine Zinfandel vineyards. When these vineyards were planted in the early 1900s the vintners knew that Zin tasted better if you added a little bit of another variety that had more robust color and tannins so when the vineyards were planted, they might mix in a few vines of Petite Sirah and Alicante Bouschet for every 100 vines of Zin. The vines would all be picked at the same time and fermented in the tank together so there was a lot of time for the flavors to harmonize. The disadvantage to field blending is that all the varieties may not get ripe at the same time and some years you might want a little more or less of the other reds depending on how the Zinfandel turned out. Nevertheless, it is the simplest way to blend and if you are eventually going to mix the wines together no matter what, it is not necessarily a bad way to do things. Digital members can read more about creating field blends at home at https://winemakermag.com/technique/1731-field-blending.

If you blend the wine just after fermentation this allows you to pick each variety at the optimum ripeness and wines have plenty of time to marry together while they are being aged, and time for you to taste the blend and make further adjustments down the road if you feel it is needed.

Another option (which is the one I prefer) is waiting until after the wines are finished aging, usually a couple of months before they are to be bottled. By this time the wines are nearly finished and you get the most accurate estimation of what the ultimate flavor of the final blend will be when it is bottled.

All three approaches have their benefits and shortcomings, and it may be that certain wines benefit from one approach while others may be approached differently.

Expanding your options

For your home winery you may not have access to dozens of different wines that you can use in your blends but if you are willing to think outside of the box there are still many options open to you. If you are making a barrel of Cabernet Sauvignon from grapes, you can consider making a carboy of Merlot either from fruit or from a kit to complement the bigger lot in your barrel. Or if you have more than one vintage in your cellar from your own home vineyard, you might benefit from mixing a little of the younger vintage into the older one to freshen it up.

You can use blending to add diversity to your wines as well. If you make a Barbera and a Zinfandel you can bottle up some of each variety by itself as well as make a red blend of the two. This is a great way to add some variety to the wines at your dinner table. You can also consider trading for a bit of wine with another home winemaker (if you are a part of a wine club, there should be a good diversity of options), or even consider buying a bottle of Syrah at the wine shop to add just a bit more body and color to your Pinot Noir.

What to watch out for

Blending is a powerful winemaking tool but there are a few risks that you should be aware of. When you blend wines together you might be mixing spoilage yeast and bacteria as well. For instance, if one lot in the blend had Brettanomyces or Acetobacter growing in it, when you mix them together you would be spreading the problem to the whole blend. This can be avoided by tasting the wines first and not using any wine that has problems. A small volume of bad wine is one thing but it is much worse to have a big blend go bad because you did not taste each of the components separately before blending.

Even beneficial microbes can cause problems — when you add a wine that has finished malolactic fermentation (MLF) to one that has not gone through MLF, you will now have a blend that has the potential to go through MLF after bottling if you do not sterile filter. Usually if you mix wines that have been stabilized the resulting blend will be stable but this is not always the case. Sometimes the slight change in pH between the base wine and the blend will result in wines that were once heat and cold stable to become unstable. It is best to wait until after blending before stabilizing if you can.

At first glance the numerous options for blending combined with the computations needed to keep track of complex blends might seem a little intimidating but it does not need to be. When you are starting out keep your blends simple with just a few wines, then experiment and taste what you come up with and trust your gut. Just follow the simple rule that if the blend does not taste better than the base wines don’t do it and if it does taste better then go for it.

Happy blending!