Why blend white wines? Sometimes, it’s to make a better wine than the sum of its parts or just to have another wine in the cellar to choose on a warm summer evening. For commercial winemakers, there are additional questions of sourcing grapes in necessary quantities or hitting a particular price point. In some wine regions, particularly in Europe, blended whites have a long cultural tradition and excellent market acceptance. While most American wines, particularly in the premium categories, seem to go for varietal naming, I am pleased to see more white blends appearing on local shelves and in wineries that I visit. Sometimes I make a white blend just for the fun of it — creating a novel drinking experiment.

At home, we may also want to blend some of our white wines to adjust an out-of-balance characteristic or correct a deficiency, or simply just make a more interesting wine. Regardless of your motivation, the actual practice of white wine blending follows the same basic procedures.

Start With a Goal

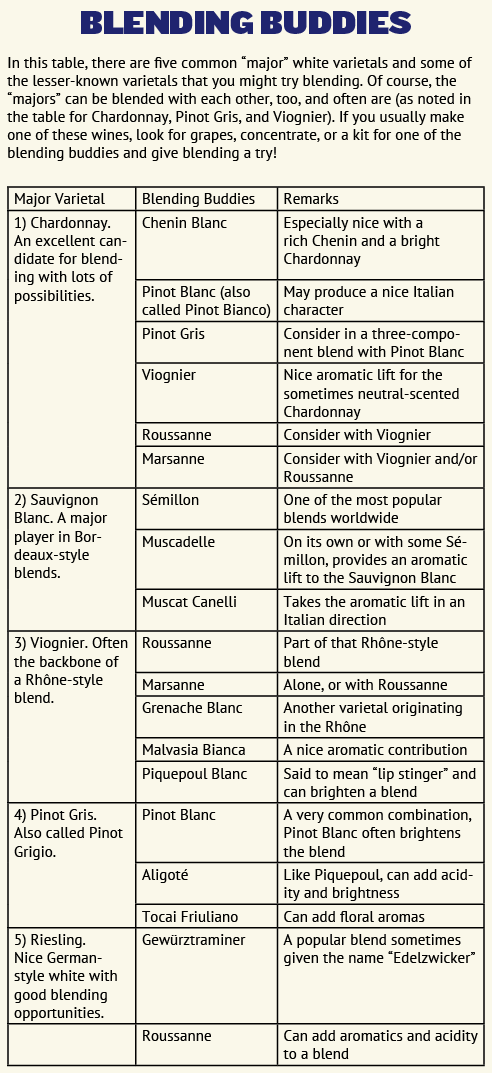

The first step to blending white wines is to identify your objective and assess the blending stock you might have available. If you grow your own grapes and have only one white variety, consider using a wine kit or purchased grapes or juice to make a compatible blending variety to add complexity in your cellar. If you make wine that consistently is out of balance or borderline, say too high in acid or too low in alcohol, you can plan a complementary blend to correct that. As to choosing varieties, the sky is the limit, but certainly some work better than others (see the chart at the end of this article). Most of the time, it seems to work best to use just two or three varietals in making a wine blend. Blending can increase complexity — usually a desirable goal — but too many components may just cancel each other out. In the book Modern Winemaking (Cornell University Press, 1985), author Philip Jackisch advises, “Excessive blending can reduce any wine to mediocrity.”

Methodology

Methodology

Any blending project requires tasting trials. For adjustment of a wine for improvement, the tasting may be mostly to confirm the results of a math calculation. For projects just looking for a better wine, or to add another wine to the cellar, the tasting will be the primary guide. I will first describe the procedures for “adjustment” blending, and then discuss those that are just for pleasure — “hedonistic” blending.

Although you can taste wine for perception of too little acid or too much alcohol, those kinds of measurable parameters are better addressed through laboratory testing. You can easily do an acid test yourself with a test kit or a buret and a pH meter, but you will probably need to send your wine to a winery laboratory or a commercial wine laboratory for alcohol analysis. Of course, if you started with a sugar (Brix) level that was unusually high or low, you can anticipate the corresponding high or low alcohol result.

Suppose you make a warm-climate Chardonnay that started at 26 °Brix and finished at 14.3% alcohol by volume (ABV). That level may be unpleasantly high, causing a “hot” sensation when tasting the wine. If you can also make a cool climate wine — the same or a different white variety — at a lower alcohol level, you can blend to a target value. In this case, suppose you made another lot of Chardonnay picked at 18 °Brix with an ABV of 10%. If you choose a target value of, say 12.5% ABV, you can use a tool called the Pearson Square to solve the equation for your desired result. In his book Techniques in Home Winemaking (Véhicule Press, 2008), author Daniel Pambianchi describes its use for several situations. For this article, here is the alcohol adjustment example that I just described. The square looks like this:

A D

C

B E

In this square, “A” is the concentration of the wine to be adjusted, in this case our high-alcohol Chardonnay at 14.3%. “B” is the concentration of the blending wine, in this case 10%. “C” is the target value, 12.5%.

The other values in the figure are calculated as follows:

D = C – B and is equal to the “parts” of wine “A” to be used in the blend (read straight across the table)

E = A – C and is equal to the “parts” of wine “B” to be used (again, read straight across)

So:

14.3 2.5

12.5

10.0 1.8

Which means for every 2.5 parts (say, gallons or liters) of wine A you use, you will need to blend in 1.8 parts of wine B.

The same approach can be used for adjusting acid, residual sugar, or other characteristics that may be out of balance. For winemakers comfortable with algebra, Pambianchi also presents adjustment calculations in that format. However you do the calculation, make a small trial blend first and taste it alongside the single components. If it is better, go ahead with the blend. If not, try another plan. If you do make the blend, plan on holding it a month or so before bottling. Sometimes wine blends will reveal instability and cause something to precipitate out, even when the component wines were individually stable. Even though the component wines are stable, the blended wine needs to be stabilized on its own as its chemistry could potentially have changed.

“Fixing” Wine with Blending

While very useful for adjusting wine (or calculating spirit additions for fortified wine), note that blending alone is not usually prudent for correcting actual wine faults. If you have high hydrogen sulfide levels or noticeable oxidation, trying a blend will usually just taint a larger quantity of wine and not produce a satisfactory result. Some authorities make an exception for marginally high volatile acidity, insisting that it can be diluted out to an acceptable level. In my own winemaking, I would consider the chance of spoiling the whole batch too risky to try it. Discard or treat a flawed wine, do not ruin a good wine by blending it with bad.

Most of the wine blends that I have made were for pleasure, rather than fault correction. A few times the component wines have simply been complementary and I blended most of the lot just to have a better tasting wine. More often, though, I have been looking for more variety in my wine cellar when I choose something to drink.

Blend Inspiration

Blends can be the same variety from multiple vintages or locations, the same lot of grapes fermented with different yeasts or barrel programs, wines grown in different regions, or many others. Most common, though, will be blends made from different varieties of grapes from the same vintage year and probably grown in nearby areas. To plan such a project, we can look at famous white blends from around the world. For example, in Bordeaux, France white wines are commonly blended from Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon. See the chart at the end of this article for additional suggestions. Avoid trying to blend too many different wines. However, if you do want to try three or more, you may find it easiest to make a two-component blend that you like first, then use that as a candidate in blending with the next wine.

These blends for pleasure depend on pleasing the palate rather than solving an equation. Ferment, age, and sulfite the individual wines as you normally would. After that, set up trial blends. Get one or more trusted wine-loving friends or family members to taste with you. Based on the stock of wine available and with knowledge of likely compatible blends, prepare tasting samples. For this, I use a 375 mL sample bottle of each of the two wines I will be blending. Then I prepare 100 mL blends using a graduated cylinder. The 100 mL size is convenient because each mL represents one percent in the blended sample. The resulting size, a bit less than four ounces, allows three or even four tasters to try the wines. Putting the blends on a marked paper placemat will make it convenient for your tasting partners as they can take tasting notes directly on the placemat and then leave it with you after the trial. Besides the wines individually as controls, I will often start with three ratios like 1⁄3-2⁄3, 1⁄2-1⁄2, and 2⁄3-1⁄3. Some authorities recommend tasting blind, but I do not usually do that. It does not matter to me if my tasting companions have a bias about a particular varietal as I will accept their input but ultimately make the blending decision myself.

Practice Blending

To help plan a white blending project, develop your palate for these wines. (It’s hard work, but someone’s got to do it!) Try commercial white blends when you are wine tasting and note the composition. When buying a commercial bottle of white wine, do not overlook the “generic white” aisle. Very often some of those wines will be interesting blends that can introduce you to something new. Check the back label for varieties and, hopefully, ratios to help you determine what you might like. Even if it is not on the label, the winery website may tell you more about it.

Novel blends may show up anywhere. Working as a volunteer at a commercial wine competition recently, I read the back label of a French wine that was listed as 60% Sauvignon Blanc and 40% Loin-de-l’oeil, a grape variety I had never heard of. Of course, I made a point of tasting that wine when the judging was over. While wine tasting in California, I have run across excellent examples using traditional combinations like Carol Shelton’s Coquille Blanc made from a Rhône-like selection of Grenache Blanc, Roussanne, Viognier, and Marsanne. Far from conventional, but a long-time favorite, has been the blend from Brander Vineyards called Cuvée Natalie, made from Pinot Gris, Sauvignon Blanc, and Riesling. Sometimes even a varietal-labeled wine is actually a blend, such as my long-time local favorite Sauvignon Blanc from Selby Winery. Susie Selby uses 3% Sémillon and 2% Muscat to boost the tropical notes while still meeting varietal wine percentage requirements. And do not forget what my good friend Martin Snider calls the “kitchen cuvée.” If he has a small amount of wine left in a bottle when he opens a new one of something else, he makes a quick blend in a glass just to see what the effect may be. For WineMaker readers who attend the magazine’s annual conferences, you can make a whole game of this at the various events — make kitchen cuvées on the fly as you taste. And take notes, always take notes. Now get out there and blend some white wine!

Pro Winemakers on White Wine Blending (by Danny Wood)

Neil Collins, Executive Winemaker, Tablas Creek Vineyard

Neil Collins, Executive Winemaker, Tablas Creek Vineyard

Tablas Creek Vineyard is in California’s Paso Robles AVA. The winery focuses on Rhône blends, including whites made from Roussanne, Viognier, Marsanne, and Grenache Blanc grapes.

What’s most challenging about blending whites?

Neil Collins: I would see it as advantages rather than challenges. A good example for us — and obviously this is area and site specific – our Roussanne tends to lose a lot of its acidity as the sugar gets up, so the introduction of the Grenache Blanc and the Picpoul Blanc, which perhaps don’t have the same body and weight as the Roussanne, brings that acidity to the blend.

So I think it’s a benefit for us to have the option of using the more acidic varieties to help out the weightier varieties. As the wines ages they help each other out all the way down the line.

When do you blend and why?

Neil Collins: Every lot is fermented separately. We harvest in small, very selective lots and we keep those lots separate until blending. I think our first sit-down is the end of March when we’ll taste through blind every single lot that we have in the cellar and make assessments and then start building our blends from there. It’s all done by consensus and the blending is entirely done on palate.

Do you co-ferment?

Neil Collins: I’m sure there are people doing co-ferments and I’m a fan of that also but we have our specific model and technique. We do the occasional co-ferment during the harvest if it seems appropriate. For example, in this last 2016 vintage, we did do a 1200-gallon (4,560-L) foudre of 75% Roussanne and 25% Picpoul Blanc and that’s turned out to be a pretty nice tank which we hope will go into the Esprit de Tablas Blanc, but again, that will depend on how it blind tastes amongst the Roussannes.

Do you always agree on the make-up of the blends?

Neil Collins: When you have so many different personalities around the table, like Chelsea who works in the cellar with me who is a thirty-year-old woman from California, and then you’ve got Robert Haas who is a ninety-year-old man from Vermont, you know there’s a difference in palate there. Not to mention if you throw in a Frenchman (a member of the Perrin family from Château de Beaucastel who founded Tablas Creek with Haas in 1989.) But I think that ends up giving us a more complete and complex wine than if it were just me making all the decisions by myself.

In the end we taste a line-up of three versions of a blend and we’re all at least very close to the same page. Often someone will concede and say, “I can see both sides so let’s go there.”

What do you do to the wine after fermentation?

Neil Collins: I buy very few new barrels. For a winery that is producing up to 28,000 cases, my annual barrel purchase may be 12 barrels. The only whites that you’ll taste from me that have perceptible oak are the Roussannes.

We do a lees aging until the first racking. The Esprit and the Roussanne are blended and then put back over their lees and aged through the following harvest and bottled in the spring.

What do you enjoy most about making white blends?

Neil Collins: I think it’s the excitement of the blending process. It’s pretty cool when we all sit down as a group and taste all these lots blind, which can be upward of over a dozen Roussannes, and seeing what the harvest gave you; seeing which blocks excelled and which blocks didn’t do as well as you thought they might.

What’s the most important thing you have learned during your years of experience making white blends?

Neil Collins: I think it’s to make sure you taste your components blind and really trust your own palate and what you like. Go at it not knowing which is which and what you’re tasting and really trust what your palate is telling you.

Chris Upchurch, Executive Winemaker, DeLille Cellars

Chris Upchurch, Executive Winemaker, DeLille Cellars

DeLille Cellars in Woodinville, Washington specializes in Bordeaux-style blends. The winery’s 2009 Chaleur Estate Blanc White, a blend of 67% Sauvignon Blanc with 33% Sémillon, scored 95 points from Wine Enthusiast.

What do you want each grape variety to bring to your white blend mix?

Chris Upchurch: It’s actually a three-part thing for us. Blending trials are the same for reds or whites, you want each grape to have its own sign and contribution but you also want a whole is greater than the sum of the parts type of thing as well. You want a harmony and seamlessness as well.

As far as the white Bordeaux blend, basically you get the power, strength, size, the citrus, grass, and all those things from the Sauvignon Blanc.

From the Sémillon you get fatter, rounder flavors with honeysuckle aromas, dried fruit, figs, more viscosity — things like that.

We add a third component to it which is our sur-lies barrel aging and when we perform bâtonnage (lees contact and stirring) the wine, for four to six months usually. That encompasses the yeast into all this and gives it more of a creamier, or what we call a crème-brûlée characteristic, that sort of wraps around the wine with its creamy character. That sounds pretty good doesn’t it?

That’s the idea behind our blending and to do it in a way that you get all the characters so one doesn’t dominate.

With our white blend we’re right around two-thirds Sauvignon Blanc and one-third Sémillon. We adjust that every year, we’ve gone up to 70% and down to 60% Sauvignon Blanc, but it’s always in the lead. So it’s a classic blend, we’re looking for a similar thing to everyone else and then we’re balancing it out with our own fruit and what percentages and what vineyards we need to make it harmonious in our own wine.

What’s most challenging about blending whites?

Chris Upchurch: In general I’d say the Sémillon is the most challenging both in the vineyard and in the cellar. I should start off by saying that we are a red wine house — we produce 80% red wine — but I may be most proud of our white blend because you don’t find a lot of white Bordeaux blends around the New World, and the biggest reason for that is the Sémillon. I mean California has pretty much given up on it. Sémillon is really not a new world varietal, it gets too fat, but up here in Washington it actually does really well. And because Sauvignon Blanc grows everywhere it’s really the Sémillon that allows me to make this blend that other people from California and wherever really don’t do as good of a job on.

I really feel it’s a unique wine in the world — it’s a white Bordeaux blend with new world brightness that gives it an extra dimension but still all the complexity of blending those two grapes together.

When do you blend and why?

Chris Upchurch: White Bordeaux blends are always blended after fermentation. Your options are done if you do it before.

For DeLille in particular, everything is focused towards the blend and blending trials. We get wines from 60 different blocks in the state and then we set out to make 15 wines and it’s all focused on more and more blending options not less.

We do dissect the wine and look at the acid levels, tannins, and all those things when we taste, but we’re really looking for that structure and harmonious balance more than anything else. For me, I like different characters in wines and I don’t care if it’s red fruited or black fruited, I’m much more concerned that it’s beautifully proportioned and has some kind of grace and elegance to it as well as power.

So it’s the same blending trials for everything you do, reds or whites, you just want everything to contribute, but contribute in a harmonious way.

What do you do to the wine after fermentation?

Chris Upchurch: We do barrel ferment in French oak, and we perform bâtonnage, stir it once a week, and from that we do the blending trials.

Actually, for our blending we like to repeat our blends a month later because we want to make sure that

one of the components isn’t changing too much, or is changing in the right direction.

What single piece of advice could you give a new winemaker starting out making white blends?

Chris Upchurch: It’s a little bit tougher for home winemakers because you get small amounts from one or two places and you’re kind of limited with that, but I would look at prototypes. For example, if you like my wine, maybe try two thirds — one third Sauvignon Blanc-Sémillon, you might go for that. But you’ve got to use your own palate for direction.

What’s the most important thing you have learned during your years of experience making white blends?

Chris Upchurch: One thing I learned a while back, in 1993 or 94, from David Lake (Washington wine pioneer), who was kind of my mentor, is that your best wine may not be appropriate for the blend and your worst wine might actually add something to it, at least in small percentages. Don’t automatically assume that your best wine should be your best part of your blend. I’ve also seen over the years that 10% of another wine that you may think might be underripe, or something that’s not your favorite wine, really adds some kind of complexity to the overall blend.

I’ve also learned that you’re basically building a wine. We’re all craftsmen and we’re all building something and if you take that kind of attitude and get out there: “Okay, what am I building today?!”

Travis Lemm (left), Winemaker and Winery Manager, Voyager Estate.

Travis Lemm (left), Winemaker and Winery Manager, Voyager Estate.

Voyager Estate is located on the Margaret River in Western Australia. Voyager’s Sauvignon Blanc–Sémillon 2014 received a 94 point ranking from James Halliday’s Australian Wine Companion.

What do you want each grape variety to bring to your white blend mix?

Travis Lemm: Sauvignon Blanc brings aromatic lift with upfront tropical fruit characters and Sémillon provides the fine acid line, palate weight and structure with citrus elements.

What’s most challenging about blending whites?

Travis Lemm: Ensuring the balance is achieved between the varietals. Both varieties can show variations each year, so the percentages of each in the final blend is a difficult challenge. Secondly, the amount of oak fermentation we use varies each year depending on the textural elements we want to achieve in the final wine.

When do you blend and why?

Travis Lemm: After fermentation – each wine is fermented separately and therefore assessed individually. Some parcels may require lees stirring, earlier or later sulfur additions, time in oak etc.

What do you do to the wine after fermentation?

Travis Lemm: A portion of the Sémillon is fermented in new French oak for two months to add texture

and complexity to the wine, the remainder of the wine is held in stainless steel tanks until blending and bottling with varying degrees of lees contact and stirring.

What single piece of advice could you give a new winemaker starting out making white blends?

Travis Lemm: Some believe in travelling lots and seeing lots of regions, which is fun and exciting, but you really only see harvest, you don’t see the actual winemaking that occurs over the rest of the year. So for me, it is find a great place that makes awesome wine and stay there for a while. Build your experience beyond just dragging hoses.

What’s the most important thing you have learned during your years of experience making white blends?

Travis Lemm: Try not to second guess yourself. If it looks right and the benchmarks are met, blend it.

Methodology

Methodology

Neil Collins, Executive Winemaker, Tablas Creek Vineyard

Neil Collins, Executive Winemaker, Tablas Creek Vineyard Chris Upchurch, Executive Winemaker, DeLille Cellars

Chris Upchurch, Executive Winemaker, DeLille Cellars Travis Lemm (left), Winemaker and Winery Manager, Voyager Estate.

Travis Lemm (left), Winemaker and Winery Manager, Voyager Estate.