If someone asked me what I enjoy most about traveling, the wine geek in me jumps to the front of the line. Because my reply would have to be learning about all the varieties of grapes there are on this planet. My “go-to” reference when I first start researching a new varietal is Jancis Robinson’s Wine Grapes, where in just about 1,200 pages, she details 1,368 different varieties. There are undoubtedly thousands more when you look at the species that are not considered “wine grapes” per se, but wine is still made from them. Robinson brings up the obscure and not so obscure while detailing origins, trends, and flavors associated with them.

When I was presented with this issue’s grape varietal, before I started my research I thought for sure this was another one of those obscure varieties. But I was wrong. She dedicated over two pages to Blaufränkisch, which is clearly a lot since the obscure varieties, like Bonamico from Italy, barely get a paragraph. As I read on, I realized I know more about this grape, have tasted the wine, and actually made a little wine from it, than I ever realized.

Turns out I knew the variety as Lemberger, a red varietal, now up-and-coming in the European realm of wines.

Since the Middle Ages the word fränkisch has been given to wines of superior quality in the Germanic world of wine. The word blau translates to the word blue. But the word Blaufränkisch did not appear in writings until 1862 and was not officially adopted until 1875. A few years later the names Lemberger and Limberger were adopted based on where the variety was grown in Austria. Meanwhile, across the border in Hungary it was grown under the name Kékfrankos, which is the Hungarian translation of Blaufränkisch. Its history has been well documented since the advent of DNA profiling. It was long thought to be identical to Gamay Noir or Pinot Noir, but in actuality it is a parent of Gamay grapes and has a parent-offspring relationship of Gouais Blanc of the Pinot pedigree. Given what is know about these relationships, the origins of this varietal are likely in the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the area demarcated as Dalmacija (also known as Dalmatia).

From a viticulture point of view, this is a vigorous variety that buds early and ripens late, thus needs to be grown in areas protected from the winds and a generally warmer climate (relative to other Germanic varietals). It can thrive in a wide range of soil types, which makes it an attractive variety to grow. The vineyard area in Germany alone, which was about 500 hectares (ha) or 1,236 acres in 1970, has grown to almost 2,000 ha (5,000 acres) in 2019. Hungary was just over 8,000 ha (20,000 acres) of Kékfrankos, but sometimes you’ll find it under the lesser-known name of Nagyburgundi, to add a little confusion. Notice the “burgundi” in that name, referencing its inferred connection to Pinot. In North America, the varietal is gaining traction in areas outside of California, notably the Finger Lakes region of New York, Washington State, British Columbia, and other more temperate wine regions. More recently it’s starting to gain some traction in Pennsylvania too.

It can thrive in a wide range of soil types, which makes it an attractive variety to grow.

The wines of Blaufränkisch are quite diverse, ranging from light and fruity, to wines that are rich in extract. Technically, the term “extract” refers to everything besides water, sugar, and acidity in wines. Tannins and other polyphenols compose the majority of extract and the term can get a little muddy when you look at the dietary supplement called grape seed extract, which is purified procyanidins and other tannins, like catechin and epicatechin. For winemaking purposes, we’ll refer to extract as compounds derived from the seed, skins, and pulp of the grape. During a grape’s maturation process on the vine, generally there is an increase in extract concentrations leading to a fuller-bodied wine. But how much extract makes it into the wine will also largely depend upon how the wine is made. In Germany and Austria, the wines labeled as Spätlese and Auslese could be assumed to be bigger and bolder in that those terms refer to later harvest grapes when compared to the Kabinett wines of the region. In the U.S., some of the lighter-bodied versions of Blaufränkisch are blended with other reds, Cabernet Franc being one of them, to add structure and flavor depth.

From a winemaking aspect, I have always advocated for the minimalist approach in a home winemaker’s winery. In other words, don’t put anything extra into your wine, especially when you may need to consider having to remove it later in the process. What I am referring to in this case are the tannins and polyphenolic compounds that can lead to bitterness and astringency. This varies amongst varieties and growing conditions, but sometimes these wines just need help to build additional structure. This comes with time and experience of working with the grapes from vintage to vintage. Some producers opt to rack and return the fermenting juice, a process called delestage, to maximize the extraction of these compounds. The way I learned the process was to completely drain the fermenter of free-run juice and return the juice to the tank with the force of a fire hose. The vigorous nature of this process will fracture the skins, and any oxygen that is introduced will aid in polymerizing tannins. So what seems to be counter-intuitive to my minimalist winemaking philosophy, this winemaking technique is actually quite beneficial when working with a red grape like Blaufränkisch.

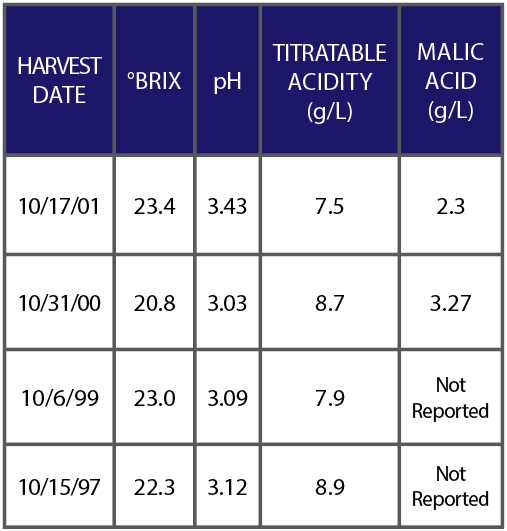

Another aspect of winemaking with a long-seasoned grape in cooler climates is acidity. The wines of Blaufränkisch are often referred to as having medium to high acidity. For me, that needs more definition, so I started gleaning the research produced from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York in the heart of the Finger Lakes for data. This particular study detailed four harvests of Blaufränkisch (though they refer to it as Lemberger) from the vintages 1997 to 2001. Juice data is as follows:

While the study is older, its data stands to represent the diversity of what a specific block of Blaufränkisch produces from season to season. The resultant wine acidities ranged from 5.5 to 7.3 g/L after the malolactic fermentation, but some further de-acidification might be necessary depending on mouthfeel. To deacidify is something the winemaker needs to evaluate critically, and not rely on the “numbers.” At one point in my career winemaking was always by the numbers because when the boss tells you to do that, that’s what you do. But a craft winemaker should always evaluate the big picture: The big picture being mouthfeel, sweetness, oak aging regime, and the bitterness and astringency parameters. So, while an acidity of greater than 7.0 g/L might be high, after the malolactic fermentation, for some reds it could be perfect for wines with the right balance. For my personal wines I advocate higher acidities to assist in aging and food pairing. I don’t rely on the number; I just want to know what it is.

Another wine style that Blaufränkisch is made into is a sparkling version, called sekt in Germany and it’s no doubt that lower-Brix and higher-acidity grapes will help develop a nice profile for such a rendition. Winemakers may also consider making a sparkling rosé the next time you have the chance. These same characteristics can also work well in a rosé.

I’m a proponent of pairing your wine with food and Blaufränkisch pairs well with a wide variety of meats and cheeses. Beef, chicken, salmon, pork, and even Korean BBQ have been reported to shine with its wines. Cheesy alfredos or risotto made with aged cheeses also will work. All this talk is making me hungry for dinner and a glass of wine! So an unfamiliar name becomes a familiar face for me in the winemaking world. I am so looking forward to our next trip to where Blaufränkisch is produced. Whether it is near or far, it’s going to be fun!

Blaufränkisch Yield 5 gallons (19 L)

Ingredients

- 125 pounds (57 kg) fresh

- Blaufränkisch fruit

- Distilled water

- 10% potassium metabisulfite (KMBS) solution (Weigh 10 grams of KMBS, dissolve into about 50 mL of distilled water. When completely dissolved, make up to 100 mL total with distilled water.)

- 5 g Assmanhausen or Syrah (EnoFerm) yeast

- 5 g Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

- 5 g Go-Ferm

- 5 g Fermaid K (or equivalent yeast nutrient)

- Malolactic fermentation starter culture (CHR Hansen or equivalent)

Equipment

- 15-gallon (57-L) food-grade plastic bucket for fermentation

- 5-gallon (19-L) carboy

- 1-2 one-gallon (3.8-L) jugs

- Racking hoses

- Destemmer/crusher

- Wine press

- Inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or carbon dioxide)

- Ability to maintain a primary fermentation temperature of 81–86 °F (27–30 °C)

- Thermometer capable of measuring between 40–110 °F (4–43 °C) in one degree increments

- Pipettes with the ability to add in

- increments of 1 mL

Step by Step

- Crush and destem the grapes. Transfer the must to your fermenter.

- During the transfer, add 15 milliliters of 10% KMBS solution (this addition is the equivalent of 50 ppm SO2). Mix well.

- Take a sample to test for Brix, acidity, and pH. Keep the results handy.

- Layer the headspace with an inert gas and keep covered. Keep in a cool place overnight.

- The next day sprinkle the Fermaid K directly on the must and mix well.

- Prepare yeast. Heat about 50 mL distilled water to 108 °F (42 °C). Mix the Go-Ferm into the water to make a suspension. Take the temperature. Pitch the yeast when the suspension is 104 °F (40 °C). Sprinkle the yeast on the surface and gently mix so that no clumps exist. Let sit for 15 minutes undisturbed. Measure the temperature of the yeast suspension. Measure the temperature of the must. You do not want to add the yeast to your cool juice if the temperature of the yeast and the must temperature difference exceeds 15 °F (8 °C). To avoid temperature shock, you should acclimate your yeast by taking about 10 mL of the must juice and adding it to the yeast suspension. Wait 15 minutes and measure the temperature again. Do this until you are within the specified temperature range. Do not let the yeast sit in the original water suspension for longer than 20 minutes.

- You should see signs of fermentation within about one to two days. If you use the Assmanhausen strain, be aware the lag phase can take an extra day or so.

- You need to have on hand the ability to push the grapes back into the juice to promote color and tannin extraction. This is called “punching down” and should be done three times per day. Use a clean utensil or your hand to mix.

- At about 19 °Brix, sprinkle in the DAP and punch down.

- Monitor the Brix and temperature twice daily during peak fermentation (10–21 °Brix). Morning and evening is best and more often if the temperature shows any indication of exceeding 86 °F (30 °C). If necessary, cool the must by placing frozen water bottles in to the fermentation or turn on your chiller unit. Do not add dry ice! Do not cool off to less than 81 °F (27 °C). Alternatively, you may need to keep the must warm if you live in a colder climate region.

- When the Brix reaches 0 (about 5–7 days), transfer the must to your press and press the cake dry. Keep the free run wine separate from the press portion for now. Be sure to label your vessels to keep the press portion separate and identifiable!

- Transfer the wine to your carboys and one-gallon (3.8-L) jugs. Your press fraction may only be a gallon or two (3.8–7.6 L). Make sure you do not have any headspace in your containers. Place an airlock on the vessel(s).

- Inoculate with your malolactic (ML) bacteria. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions on how to prepare and inoculate. Cover the tops with an airlock to allow CO2 to escape.

- Monitor the malolactic fermentation using a thin layer chromatography assay available from most home winemaking supply stores. Follow the instructions included in the kit.

- When the ML is complete, add 2 mL of fresh KMBS (10%) solution per gallon (3.8 L) of wine. This is the equivalent to ~40 ppm addition.

- Place the wine in a cool place to settle, such as a refrigerator.

- After two weeks, test for SO2, adjust the SO2 as necessary to attain 0.8 ppm molecular SO2. (There is a simple SO2 calculator at www.winemakermag.com/sulfitecalculator). Check the SO2 in another two weeks and adjust. Once the free SO2 is adjusted, maintain at this level. You’ll just need to check every two months or so, and before racking.

- Consider using oak chips to add some additional flavor and structure to the wine. But don’t just add the chips and leave them in. Taste the wine and when you get what you want, rack the wine away from the chips.

- Rack the wine clean twice over the next 6–8 months to clarify.

- Once the wine is cleared, it is time to move it to the bottle. This would be about eight months after the completion of fermentation.

- Make the project fun by having a blending party to integrate the press fraction back into the free run. You may not need it all, use your judgment and make what you like.

- Filtration is generally not needed if SO2 levels are maintained and there are no surface films or indications of subsequent fermentations. Consult Winemakermag.com for tips on fining and filtration if problems are evident. If all has gone well to this point, given the quantity made, it can probably be bottled without filtration. That said, maintain sanitary conditions while bottling. Once bottled, you’ll need to periodically check your work by opening a bottle to enjoy with friends.