Bottling Tips and Wine Judge Etiquette

Q I think it’s almost time to bottle my wine (a 2021 Chardonnay that has completed malolactic fermentation — although this is my first wine ever, so I’m not totally sure) and I have to admit I’m a little intimidated by the process. I’m planning to rent a hand corker and have my bottles and corks ready to go. I also have a couple of friends who are willing to come over to help. How do I know when it’s time? The day-of bit is also what I’m worried about. Can you give me a checklist of things I should do leading up to my “bottling run” to help me get ready?

Emily Rodgers

Wenatchee, Washington

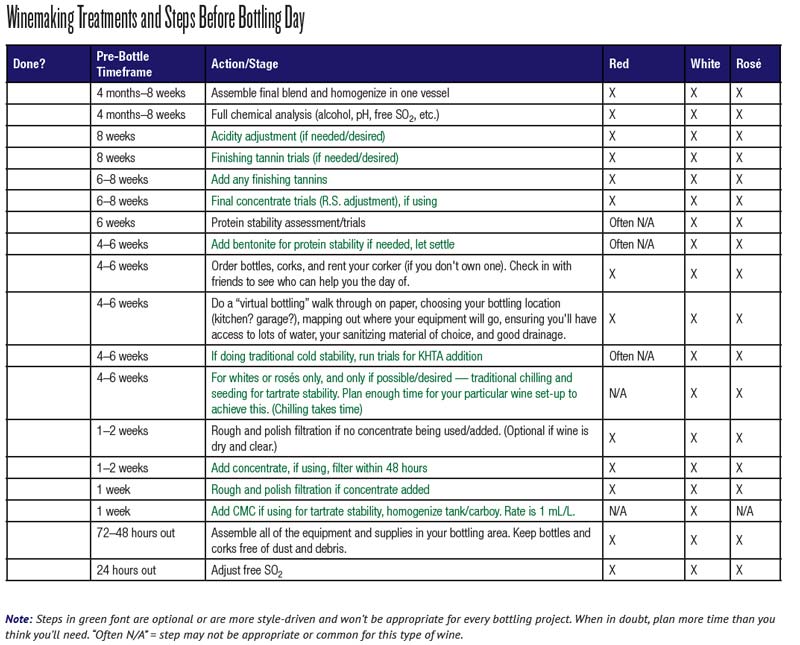

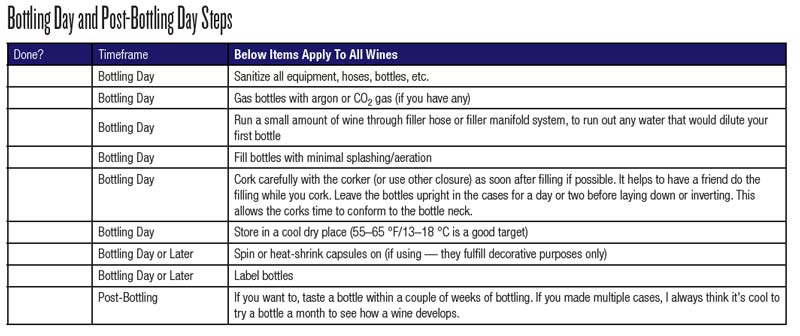

A I totally get it! There are some great articles about bottling in the WineMaker article archives at www.winemakermag.com. Though it’s a topic my fellow authors have covered before, I certainly can still give you some of my own insights as well as a checklist which is based on what I use when I’m prepping to bottle my own wines at Plata Wine Partners in Napa, California.

The first step is to determine when it’s time to bottle. Sometimes the wine just has to “do its thing” and you just have to pay attention. Since you’re dealing with a white wine like Chardonnay and it’s vintage 2021 (as I’m writing this, it’s the end of May 2022), chances are that it’s ready to go. Whites and rosés almost always need less aging time than reds, with unoaked styles (like Pinot Grigio) needing the least time.

All fermentations are complete

Unless you want bubbles appearing in the bottle later, make sure your wine is dry (I usually go with less than 0.2% residual sugar as the benchmark) and your malolactic fermentation (MLF) is either complete or has been arrested by adding a good dose of potassium metabisulfite (sulfite).

A lack of flaws

It should go without saying that the time to deal with any flaws or issues is before bottling. Wine that is too tannic needs more time or a protein-fining agent. Wine that is too sour needs to either a) finish MLF or b) be deacidified with potassium bicarbonate or potassium carbonate. Sometimes you can hide minor flaws by bringing in some other wine to blend. However, be careful of trying to hide a truly flawed wine by adding too much of your good stuff; I always say, “Never blend a loser.”

The wine is clear

Has the wine “fallen bright,” i.e. it’s not cloudy or turbid? If your Chardonnay is still hazy, try adding some bentonite or another fining agent to help drop out the solids. More on this later in this reply.

Flavors and aromas are developed

Wine that is bottle ready “smells like wine” (sorry, I know that sounds obvious) and not like an active fermentation. The oak that you may or may not have added should be smelling and tasting integrated, like it’s a natural part of the wine and not just “laying on top.”

The wine is stable

“Stable” may be somewhat subjective and is a term that definitely exists on a spectrum. For reds, what I mean by stable is that fermentation and microbial activities are all complete, the wine is clear, the flavors and aromas have developed as mentioned earlier, and importantly, no more solids are falling out of solution. Presumably the wines have been racked off heavy solids at least twice within the first six months of life or so. Keep in mind most commercial fine red wines are bottled with at least one year of aging, often with a good 18 months in barrel. White and blush wine bottling dates are a lot more subjective and their timelines vary quite a bit. Unoaked styles that rely on their freshness for their charm, like Pinot Grigio and most rosés, can be bottled very soon after dryness. With added fining to drop out lees and filtration for clarity, it’s possible to have bottle-ready dry white wine within three months or so of harvest. Chardonnays, I tend to find, take more time. They rely on time on lees and often on oak in order to get to a satisfying style that is varietally and traditionally correct, but we are still only talking about a matter of months.

It should go without saying that the time to deal with any flaws or issues is before bottling.

For whites and rosés, especially, stability also means heat and cold stability. I won’t get into it a ton here (because you can look up further references in my The Winemaker’s Answer Book, available at winemakermag.com /product-category/books) but a wine is considered heat stable (in rough parlance) if it doesn’t throw a haze when heated. A wine is considered cold stable if it doesn’t throw a precipitate of potassium bitartrate crystals when chilled. Different wineries have different chemical analysis standards for how they test and measure this, and for home winemakers it can be difficult to achieve. Getting a wine heat stable involves adding bentonite clay and racking the wine off of it. It may not be necessary if you are happy with the appearance of your wine, and you know that you’ll be able to store it in a cool environment.

In the past, it’s been especially difficult for home winemakers to achieve a level of commercial cold stability by chilling/freezing wine. Typical procedures include chilling a wine to 32 °F (0 °C) for 48 hours, seeding with cream of tartar, and then filtering the wine. It’s quite an involved process. Luckily there is a relatively new tool on the market that naturally inhibits crystallization in white wines, carboxymethylcellulose, or CMC. Now it might sound chemical-jargony but so does deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

CMC is a food-grade, water-soluble polysaccharide derived from cellulose that doesn’t change the pH, flavor, or aroma of wines. It blocks the nucleation site of seed crystals and restricts further crystal growth. It’s available in dried or liquid form from winery supply companies like Laffort or Scott Labs and is added at a standard rate of 1 mL/L (as with any winemaking tool, please read up on a supplier’s website for more detailed information). Just mix into wine that’s bottle ready and the chance that you’ll have crystals formed in wines later in its lifetime are dramatically reduced. A couple of caveats: It’s important for the wine to be heat stable (proteins removed with bentonite) before the addition of CMC or it may throw a haze. Similarly, CMC is not for use in pink or rosé wines because the colored compounds can create a haze.

I ran on way more about stability than I meant to but indeed, it is a huge topic! Good luck with your first bottling run.

Q I’m pretty active in my local winemaking club and have been entering my own wines into home winemaking competitions for a few years now. I got invited to be a judge at our county fair this year by a wine buddy and the judging is happening in a couple of weeks. Since I’ve never done this before, can you tell me what to expect and give some tips on what not to do? If I like it I’d love to be asked back again next year.

Mark Seaton

Fort Wayne, Indiana

A Congrats on getting invited to your first ever wine judging! I’ve been judging wine competitions, both for home and commercial winemakers, for over 15 years now and they’re always a great way to keep your palate fresh. You’re right to assume that there is some protocol involved, as well as some “to do’s” and some “not to do’s.” Following are some of my favorite informational tidbits to help you know what to expect, how to have a good day-of, as well as to increase your chances of getting asked back next time.

Wine competitions are usually either run by local wine clubs, as part of a fair, or by various publications. Entrants pay the organization a fee per bottle, which helps pay for the venue, supplies, and logistics. Panels of judges then taste the wines blind (i.e. they don’t know the producer or the AVA, etc.). It’s almost always an unpaid, volunteer activity. The folks who organize and put it on are also almost always volunteers too — and these things take a lot of time to put on, so it’s important to always treat them with the utmost respect. You’ll see that many of the items on the list below are about being respectful — a key to becoming a respected wine judge yourself.

- Know where you’re supposed to go well ahead of time: One of the keys is to show up slightly early, or on time. To do that, make sure you know your destination, the parking situation, if you need a permit and the traffic patterns in the area the day you’ll be traveling.

- Keep your scents to a minimum: Bathe with unscented products the morning of and definitely don’t wear any perfume or cologne. Be careful of wearing a jacket or sweater that may contain scent or tobacco smoke from previous days. These smells can linger and disrupt your palate and that of others.

- Eat a good breakfast with lots of protein: You want to be well-fortified, but no garlic or onions. Even though you’ll be spitting, you’ll still be absorbing some alcohol during the course of the day. Avoiding onions and garlic makes sure you won’t be bringing anything malodorous to the judging table.

- Show up on time: This is obviously critical and leaves an impression.

- While others are judging, minimize noise: You’re likely to know other folks who are also judging. There’s definitely a time for socializing and networking, but not when your table or others are “on the job.” Even though there will always be a low buzz of chit chat in the room, it’s never done to be boisterous or interrupt a group of judges mid-flight. If you need to approach someone during judging time, do it quietly after a flight is complete. Otherwise wait until lunch or other judging breaks for catching up with friends.

- Be respectful of volunteers/clerks: Every competition I’ve judged has been set up so that flights of anywhere from 6–14 wines in a class will be set before a team of three to five judges. Each judge quietly evaluates his or her wines, taking enough time to spend time with each, but moving at a professionally quick clip. Often, each table has an assigned clerk who records score or rank of each wine in the set (and sometimes the award). There may also be other assistants in the room who will bring the flights out to the tables, clear the tables, and empty the dump buckets. These folks are almost always unpaid volunteers so please be polite and cheerful with them — they’re doing it as a labor of love!

- Eat a good lunch: I’ve never been to a wine competition where lunch isn’t served. Having something in the stomach, as well as staying hydrated, is key to happy judges and to getting good results from the judges (which is the ultimate goal of the competition, after all). Some “old school” competitions serve beer during lunch as a palate cleanser . . . definitely not necessary, even if somewhat traditional.

- Spit, stay hydrated, and stay focused: If you finish your flight before your fellow panelists, it’s OK to check your Instagram account. Just be sure you’re ready to focus when it’s time to focus. Always spit using the cups provided and drink plenty of the provided water throughout the day. Slipping under the table at your first wine competition is never a pretty look and is guaranteed to make sure you don’t get a return invite.

- Ask questions: Not sure how the scoring system works? Not sure if you’re supposed to rank the samples or award “medals” like bronze, silver or gold? Not sure what Brianna varietal wine should taste like? Be sure to ask your table clerk or the organizers if you’re unsure. Often, it’s important to think with your “consumer hat” and even if you don’t personally like a wine style presented, try to evaluate it against its peers on its own merits.

- Send a thank-you note to the organizer: Your mom was right. Even if it’s an email, a kind thank-you note is always appreciated by the organizers!

But . . . most of all, take your time and have fun. There’s so much camaraderie to be had in the world of wine judging, it’s always one of the things I enjoy most about my job.