We’ve been making wine from our estate vineyard for 10 years and have reached a point where we enjoy experimenting and trying new things. Our winemaking experience precedes this going back to 2011. Now, because we have five different varieties planted on our property, our “spice-box” of varietal characteristics give a large canvas from which to work to produce different wines through blending and other winemaking styles and approaches.

So it is, in our 2024 harvest we decided to pivot away from our traditional single-varietal wines and post-fermented wine blends. Because we live in the Sierra Foothills of California, where Italian immigrants in the late 1800s and early 1900s planted vineyards with their ancestral varietals, we thought we would dive deeper into their approach with planting and winemaking. This influenced our desire to do a field blend in which we would co-ferment several different varieties together.

Before sharing some of the things we did in this vintage, let’s take a step backwards in time and look at these historical perspectives of field blends.

History of Field Blending

Folklore often drives a good story, and a good story can drive a winery’s promotional appeal to the consumers. While living in the Fiddletown AVA of California’s Sierra Foothills, we have heard many good stories based on the historical contributions of the Italian immigrants who settled in this area. Some might be considered ghost stories, since many of these historical wineries and their vineyards no longer exist nor remain in their family’s generational custody. Although it’s true the region was predominantly settled by Italians during the California Gold Rush years of 1848–1869, there’s no historical record that the Italians created the concept of true field-blended wines. Research conveys the theory that this misinformation came about because it was the Italian-owned vineyards that predominately survived the Prohibition/Volstead Act of 1920–1933.

After the early California vineyards began being planted with Mission grapes by the Spanish missionaries in 1769, immigrants brought their own culturally diverse vines with them. However, these vines came on their own rootstock. Along with them came the disease phylloxera, which spread and killed many of these naturally rooted grape varieties. The industry was revived in the late 1880s as the vinifera grapes took to California’s indigenous grape rootstock. These native rootstocks can still be observed in lush waterways of Northern California.

Vineyard owners began to rebuild their vineyards or fill in holes in their vineyards with whatever grapes on the California native rootstock they could get their hands on. This was known as “the basis for economic renewal” of California’s wine industry after phylloxera.1 Zinfandel was the predominant grape that held on longest from the phylloxera outbreak. Therefore, less of this varietal was replaced.

Wine was made with less chemical analysis back then, and instead winemakers relied more on taste. Winemakers working with these hodgepodge vineyards discovered that different vines/grapes contributed more desired outcomes for their wines. Some modern winemakers believe this is the reason for “old vine Zinfandel” wines to have different characteristics when produced from different vintners.

The Italian-owned vineyards survived Prohibition as the Volstead Act allowed a percentage of the vineyards to continue to grow grapes and sell to home winemakers to meet cultural needs. This also allowed for production of sacramental wine used in the Catholic Church. It could be surmised that this is why so many believe that Zinfandel is also an Italian grape, when in fact it came from Croatia/Hungary. But this grape was in these Italian vineyards alongside many other varietals: Sangiovese, Canaiolo, Colorino, Malvasia Nero, and Mammolo to name a few Italian varietals of the time. A few other varieties known to be in these mixed vineyards included Carignane, Syrah, Petite Sirah, Alicante Bouschet, Mataro/Mourvèdre, Cinsault, and Tempranillo. Historically, this is how some of these varieties survived Prohibition and contributed to why they continue to be utilized in “true field blends.”

True Field Blends

Mark Fowler, Winemaker of Andis Winery, (Shenandoah Valley AVA, California) shares that Andis is one of three wineries that utilize the 1869 “Grandpere” Zinfandel vineyard of the region, where old vine Zinfandel grapes grow to this day and “true field blend reds” are continually made from this vineyard. Mark explains that with the vineyard’s age, and historic way of planting, it is safe to know that the Zinfandel made from this vineyard today is still a field blend as the vineyard has vines that do not look like the others.

The statement “true field blend” comes from where the entire vineyard is harvested at the same time and wine produced as a single co-fermentation. Mark Fowler shares that his approach begins with testing certain vines for Brix and the results of these particular vines determine harvest date, not by sampling the entire vineyard or from a random sample. From which vines the Brix number is tested is the quirkiness of this approach. Carignane is one of the first maturing red varieties and it is guessed that this is the Brix number the entire vineyard would be harvested from. But, there is no proof or admission to this theory. It’s all anecdotal, and the specific Brix is based on a historical knowledge of that particular vineyard.

Morgan Twain-Peterson, Owner and Winemaker of Bedrock Wine Company in Sonoma, California, presents from his thesis research; “Ridge Winery’s Lytton Springs Estate Vineyard of Napa Valley,” as well as Bedrock, Pagani, and Nervo Vineyards in Sonoma County, all present unique “true field blend” wines. All are predominantly Zinfandel with the remainder of the blend being unique to all the different plantings that remain in these historical vineyards. These unique blends of vines in the co-fermentation vary in color, character, and aroma as a result of the plantings. David Gates, the viticulturist for Ridge Vineyards compares such plantings to that of a spice rack that presents the “best wines.” (Twain-Peterson, UC-Davis, 2017)

Our Approach to a Field Blend

Loving a good ghost story, we wanted to try our hands at creating a field blend. Having decided prior to our 2024 harvest to do a field blend we started our planning process for how to do so. Unlike the early Italian vineyards that were planted with several different varieties within the same vineyard or vineyard block to create their “spice blend” for a finished wine, we did not have that option since our vineyard is segmented into different variety blocks or sections. This required us to harvest each of the varietals separately on the same harvest date and then mix the grapes together at the crush pad.

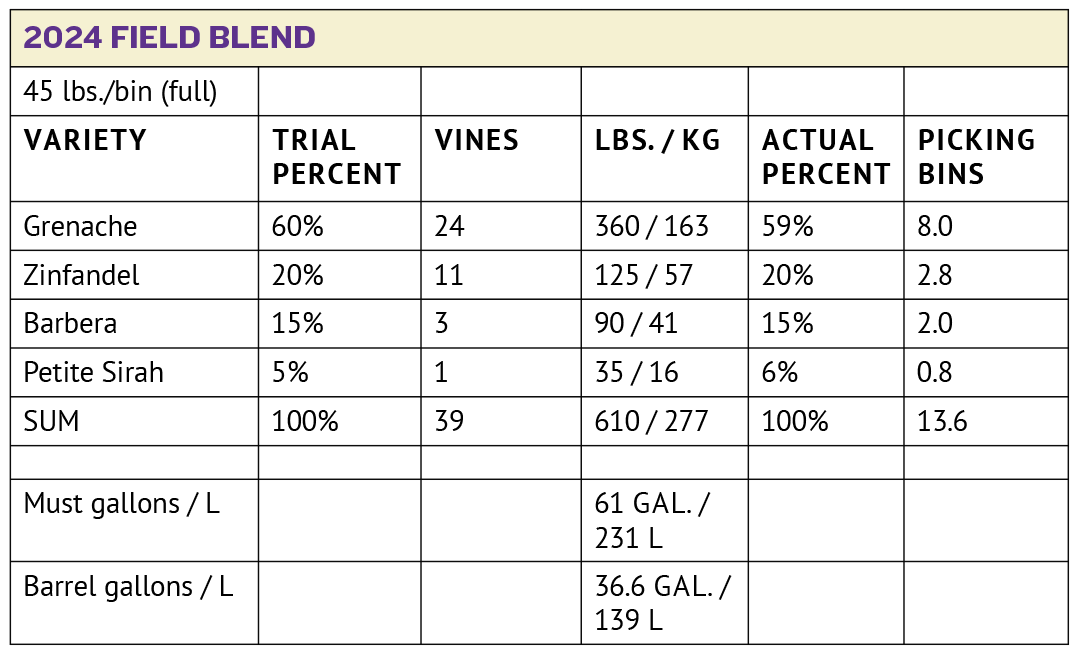

In the planning process we had to first decide what varieties we wanted in the blend and then in what percentage to make a complete wine. To do so, we used single varietal wines bottled in a previous vintage and conducted a bench trial to determine what varieties from the estate vineyard and in what percentages to recreate a field blend for our 2024 harvest. We decided on a Grenache-focused blend in the following ratio: Grenache (60%), Zinfandel (20%), Barbera (15%), and Petite Sirah (5%). This was strictly a trial and we did nothing more with these wines.

Then the question became how do we accurately recreate this blend at harvest? To do so we created an Excel spreadsheet as shown below to give us some estimation scenarios on variety volumes that would in total allow for aging in a 29-gallon (110-L) French oak barrel plus some extra for topping purposes. Taking into account how much our picking bins hold, we then determined how many bins would be needed to harvest the appropriate amount of grapes of each variety.

We used 35-gallon (133-L) fermentation containers to dump grapes from the picking bins into. The filled 35-gallon (133-L) containers were then transported back to the crush-pad for processing.

The other important consideration was; when do we pick? Taking into account the information Mark Fowler shared with us about harvest decisions in these multi-variety vineyards, our sampling of each variety led us to the decision when we should schedule the date to pick. Unlike Mark’s scenario that he shared about basing harvest on a single variety, we used a broad sampling across all varieties to schedule harvest. Lucky for us, our Zinfandel, Barbera, Petite Sirah, and Grenache fall into a small window of a harvest date timeframe. For the numbers geeks, the field blend was harvested on October 5 and the resulting crushed/destemmed must was at 27 °Brix and 3.92 pH. Total acidity was increased from 5.4 g/L to 6.8 g/L prior to fermentation.

It also occurred to us to extend our experiment so that we could evaluate the sensory differences between the co-fermented field blend vs. the traditional blending of single varietal wines after they had been fermented separately. At the time of the 2024 harvest we still had the 2023 vintage of varietal wines in barrels. The plan was to take each of the 2023 wines and create the blend based on the same percentages as intended with the field blend. This was done after a coarse filtering and about a month before bottling to let the blended wines integrate with one another. While this was not a true “apples-to-apples” comparison between a traditional blend and a field blend within a single vintage, nonetheless it offered some degree of comparison for our evaluation.

As we finalized the writing of this article we conducted a taste and sensory evaluation of the two types of blended wines. It should be noted that trying to make a comparison between the two different blending styles and judge whether or not the field blend produced a better wine was difficult. The 2023 vintage blend was just bottled 6 months ago, so it is still quite young and needs at least another year in the bottle to develop “finished wine” characteristics. On the other hand, the 2024 field blend wine is still in barrel and will not be bottled for another six months. In any case, we feel there are some general tendencies of each of the wines which we can glean a few conclusions from.

The 2023 Vintage Blend

With only about six months in the bottle, our first impression from tasting was, “Wow, this exceeds our expectations.” Being made predominantly of Grenache (leaning towards a GSM), the wine is medium (-) in body and color, with evident tannins and acidity. In other words, a balanced wine. Aroma is notably present along with fruit characteristics of stewed raisins and plums, with a hint of brown spices. These are characteristics that one would expect from the varieties within the blend. Somehow, these characteristics as a whole seem to exceed our typical single-varietal wines. We can’t wait for this wine to continue aging in the bottle for another year.

As a side note, we age our wines in the bottle for at least 18 months before considering them for consumption or competitions.

The 2024 Field Blend

This wine started out after primary and secondary fermentation as a “WOW, this is tasty, with very fruit-forward characteristics.” Therefore, the immediate conclusion at that early point in time was, “We’re onto something with this field blend co-fermentation thing!”

As time went on and the wine was tasted multiple times during barrel toppings, we started to suspect something odd. Granted, it consistently maintained its fruit-forward characteristics and a softness on the palate. Wanting to better understand the nature of this we sent the wine to the lab for testing. The results we got back were very surprising, but things now made much more sense. The wine had a low level of residual sugar.

After probably at least 50 separate fermentations in our past winemaking experiences, this was the very first time that a fermentation failed to complete to a “dry” condition. Visually, there was nothing different with this fermentation than any other. Once the hydrometer read 0 °Brix and fermentation had visually slowed, we pressed the juice to a new container to complete primary fermentation and start malolactic fermentation. It is still hard to understand where it went wrong. Brix was high at 27, but our yeast (we used UVAFERM VRB for its ability to ferment up to 17% ABV) should have handled the potential alcohol. We chose not to dilute the must with water to reduce Brix and did not want to water down the body of

the wine.

With about six months in the barrel, the wine still has a soft, fruit-forward character. The level of residual sugar is not overwhelming on the palate, and the wine would still be considered “a sound and drinkable red wine” by most consumers, even by commercial standards.

Final Conclusions

Having the historical stories as a reference to true field blends, we are still basically left with our own “ghost story” of its own in relation to our 2024 experiment. We are still wondering what the heck happened with the fermentation to produce an off-dry wine despite appropriate yeast selection and care taken. However, let it be said that the reasons why vintners past and present created a field blend and did co-fermentation were valid. As we go forward with our own winemaking efforts, we will continue to use, to some degree, a co-fermentation strategy with our blends.

A huge “Thank You!” is extended to Morgan Twain-Peterson MW, UC-Davis MS-enology, Winemaker/Owner of Bedrock Wine Co. for allowing us to read his 2017 master’s thesis for the basis of this article.

Reference:

1 Sullivan, C. L. (2003). “Zinfandel: A history of a grape and its wine.” University of California Press.