Creating Balanced Wine

For as long as I have been making wine, balance has been a paramount goal. Even when wines seem extreme in style, balance is still in there making it right. An extremely sweet Icewine? High acid brings it around. High alcohol California Zinfandel? High pH and low acidity drape it with fruit to keep the alcohol impression in check. As these examples illustrate, “balance” is not just one set of figures that applies to all winemaking. Instead, it is a combination of variety, style, fruit characteristics, winemaking parameters, and — above all — the winemaker’s goal for balance. As with so many other goals in winemaking, we need to define where we are going before we can get there.

For as long as I have been making wine, balance has been a paramount goal. Even when wines seem extreme in style, balance is still in there making it right. An extremely sweet Icewine? High acid brings it around. High alcohol California Zinfandel? High pH and low acidity drape it with fruit to keep the alcohol impression in check. As these examples illustrate, “balance” is not just one set of figures that applies to all winemaking. Instead, it is a combination of variety, style, fruit characteristics, winemaking parameters, and — above all — the winemaker’s goal for balance. As with so many other goals in winemaking, we need to define where we are going before we can get there.

Eminent French wine scientist Emile Peynaud discussed aspects of balance several times in his textbooks. In The Taste of Wine: The Art and Science of Wine Appreciation, he addressed it in terms of structure: “Diverse flavors from acids, sugars, salts and phenolic substances…that blend into a form, a more or less harmonious volume which makes up structure.” (As quoted by Daniel Pambianchi in his book, Techniques in Home Winemaking.) In another book, Knowing and Making Wine, Peynaud assigned a quantitative measure to some of the aspects involved in achieving balance in wine. He called this goal “suppleness” and created an index for it:

Alcoholic strength – (total acidity + tannins) = suppleness index

Mid-range values, around 5, are considered “supple.” Lower values indicate a thin or harsh wine while those with higher values are considered soft and potentially “flabby.” Since there is no simple, inexpensive home analysis for tannins, the quantitative suppleness index is out of reach for most of us. Furthermore, it really only applies to red wines, as tannins are typically very low in whites. The suppleness index does not account for all of the “harmonious” characteristics we wish to consider. The principles, though, are valid and important. The take-away message is that higher alcohol levels will tend toward a higher suppleness index, risking a fat and flabby wine. Acidity or tannin levels will need to be higher in such a wine if balance is to be achieved. On the other hand, low alcohol wines risk a thin, astringent character unless acid + tannin levels are restrained as well. All of this speaks to the goals of the winemaker in converting a particular lot of grapes into a finished beverage.

Pambianchi relates those goals to varieties and styles. Fresh, dry, unoaked white wines like Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc may have relatively high acid levels but very little tannin. Their fairly low alcohol levels make them inclined to be balanced and achieve a mid-range suppleness index. Higher alcohol whites, such as Chardonnay or Chenin Blanc, may need to be made with a higher acid profile to achieve balance. Alternatively, a big Chardonnay may be enhanced with barrel aging, adding a tannin component not usually found in whites. Sweetness is also important in achieving a perception of balance. Residual sugar sometimes offsets the influence of acid and tannin in wines, but can also help balance against a high alcohol level. Some very high sugar wines, like the Icewine mentioned earlier, depend on high acidity for a balanced effect. Others, like Sauternes wines produced from Botrytized grapes grown in the French region with the same name, use a high alcohol content to achieve a desirable profile with high sweetness.

Most red wines are made dry and suppleness index goals can be more directly applied. If acidity is low, a higher tannin profile will be needed to balance. If acidity is high, tannins will need to be restrained to avoid harshness. If levels of both acid and tannin are moderate, the wine will be relatively easy to manage at almost any alcohol level. The major factors you need to consider in making a balanced wine are acid, alcohol, tannins, and sugar. Secondary factors that may influence the perception of balance include various flavor factors and even color.

Influencing Balance

To influence a factor, you need to measure — or at least assess — that characteristic. For several of them, direct measurement is feasible and can go toward a reasonable anticipation of balance. When starting a wine, whether from grapes or fresh or frozen juice or must, measuring the acidity is a basic step. TA or total titratable acidity is a titration of a must sample with standardized sodium hydroxide solution. During fermentation, TA will typically drop. In planning, look for an initial TA that is 1–2 g/L (0.1-0.2 g/100 mL or %) higher than your goal for the finished wine. There are inexpensive titration kits available for this test at home winemaking shops. If you go for a more sophisticated home wine laboratory, a buret, pH meter, and stir plate will get you set up for this test. Since pH is intimately connected to TA, it offers a similar look at balance. Low pH wines are crisp and refreshing, high pH wines are broad and soft.

For alcohol, there is no home test for the finished wine. Those who live in a wine-producing region can probably find a commercial wine laboratory that will conduct an alcohol analysis for about $20. For most home winemakers, the best bet is to estimate the finished alcohol based on the starting sugar level. Estimating prior to fermentation also gives you a better chance to influence the outcome right from the start. Sugar converts about half to alcohol and half to carbon dioxide in fermentation. There are several different approaches to estimating the alcohol by volume (ABV) based on the starting sugar or Brix. Since most of my wines finish dry, I assume all of the sugar will convert and multiply the starting degrees Brix by a factor of 0.55 to estimate final ABV. If you instead use specific gravity (SG) to measure sugar in your winemaking, you may estimate the alcohol as ABV = (Starting SG – Final SG) x 131.

As mentioned, there is no home test for tannin content. Rather than a numeric value that you plug into a formula, you will probably need to simply taste your grapes, juice, or finished wine and make a rough assessment of its tannic content. This can be informed further by knowledge of the grape variety and growing region. If you make wine from the same source year after year, prior vintages can help. Estimating your likely wine as high, medium, or low in tannins is probably good enough to help you work toward balance.

Sweetness can be measured directly. If higher than about one or two percent, you will probably be able to get a reading with your hydrometer. Keep in mind, though, that dry wine finishes at “negative” Brix or below 1.000 SG on a hydrometer because alcohol is less dense than water. If in doubt, or for low sugar levels, the best bet is to run an enzymatic or chemical test. The enzymatic methods are beyond most home winemakers, but there are easy test kits using Clinitest tablets, developed for measuring sugar in urine for diabetics.

The category of “flavor components” is more subjective than quantitative. Fruity, spicy, smoky, complex? While the various aspects may not have numeric standards, they may play into the overall considerations of balance. Contemplate how the particular flavors of that variety or this individual lot of grapes may relate to the quantitative factors. For instance, fruity character can act like sweetness and spicy notes can resemble tannins.

Then there is color. During the time I was preparing this article, my wife Marty White and I went wine tasting at Horse and Plow in Sebastopol, California. Co-owner and winemaker Suzanne Hagins was telling us about an experiment she did with whole-cluster fermentation of a small lot of Grenache. It turned out very light in color, but also quite tannic because of the stems remaining in the fermentation. Hagins noted that the conflict between what the color leads one to expect and the actual flavors made the wine seem unbalanced. Bold, rich flavors are usually matched with deeper color whereas lighter color is a token of lighter character.

Balance Adjustments

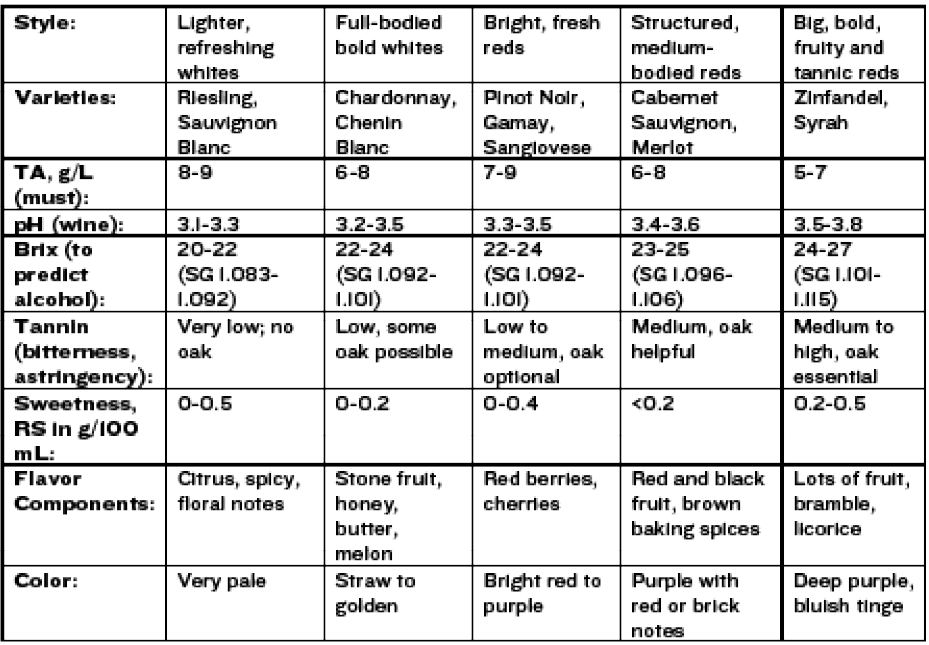

The table on page 36 displays some suggested ranges for balance in various table wine styles. Of course, other choices may make equally wonderful wine, but these examples provide a basis for discussion on how to manage the fermentation toward your goals. Note that varietal names are for reference and are not meant to be limiting. Indeed, some of the most robust red varieties can be harvested at lower sugar levels and make a light, refreshing rosé (or even white) wine. The acid (TA) figures are on the must; as noted earlier, they will likely drop a bit during fermentation and aging. Alcohol is represented by a prediction from the starting sugar level in degrees Brix or SG since that is what you can measure. “Tannin” can be taken to represent bitterness and astringency, either from the grapes or from oak aging, or both. To get these styles of wine, you will likely want to go somewhere in these ranges.

The most reliable way to get the sort of balance in the table is to start with grapes that already have the right character. As a rule of thumb, the further you try to push the wine away from the inherent characteristics of the fruit, the less likely a wonderful wine will result. Since perfectly balanced fruit is not always available, here are some suggestions on modifying the outcome.

Acid may be addressed directly. If it is too high, you may deacidify with potassium bicarbonate or potassium carbonate. If it is too low, add tartaric acid.

For Brix or SG, increasing it is easy: Add sugar to the desired starting level. If it is too high, you need to add water to dilute, then readjust acid since it will be diluted also.

To some extent, tannin levels are inherent in the grapes. You can have some influence, however. To increase tannin for bold white wines, consider barrel fermentation, barrel aging, or oak product additions (tannins are rarely too high or in need of reduction in whites). For reds, to minimize a tannin profile, be sure to remove all stems at the time of crushing. Also consider rack-and-return fermentation (delestage), allowing the removal of seeds as you proceed. Another way to reduce the tannic profile is to press earlier, at perhaps four or five Brix (about 1.016 to 1.020 SG) instead of waiting to reach zero. Less seed contact as the alcohol level rises will result in less tannin extraction. If, in spite of such steps, your finished wine shows too much astringency or bitterness, you can fine it. Use a protein agent like egg whites, milk, gelatin, or isinglass to bind with tannins and drop them out. All of these reduce astringency. If bitterness is the particular problem, milk fining has an advantage in that lactose (a non-fermentable sugar) will dissolve in the wine, slightly sweetening it and balancing bitterness.

To increase tannins, consider an extended maceration to get more extraction. You may want to mix back in some stems during fermentation — perhaps 10%. This is a technique often used in Burgundy to help produce more tannic red wines from Pinot Noir grapes. You can also make direct tannin additions during and after fermentation or at bottling. A wide variety of tannin products is available for use at any stage in the process. Oak products and barrels also introduce tannins to the wine. Barrel aging, in particular, will help with tannin development and rounding-out of the wine’s mouthfeel.

For most table wines, you will want to finish with a very low sugar level to make dry wine. A slight off-dry character can sometimes improve balance in light whites, light reds, rosés, and very fruity reds. If the finished wine seems excessively dry, run a sugar addition trial and see if you like the wine better. If you add sugar before bottling, be sure to use sorbates to prevent refermentation (note that use of sorbates is not recommended for wines that have gone through MLF as they will produce an unpleasant geranium off-odor). For very sweet wines, there is another entire series of balances to consider. Usually, higher acid or high alcohol will help keep such wines balanced.

For flavor components, you are mostly at the mercy of the grapes themselves. One exception is judicious use of blending. If you make wine regularly from a particular source of grapes, and you find the wine lacking balance in some way, consider making a wine to blend with. For instance, Sémillon is often blended with Sauvignon Blanc to achieve desired complexity and Viognier is sometimes blended with Syrah to provide an aromatic lift.

For color, keep light whites well protected from air contact to maintain very pale color without oxidation. Bolder whites can carry a bit of color, particularly if barrels or oak products are involved. Use gentle maceration and fermentation techniques on light reds. Bright red color for these wines is assured by a relatively low pH and higher acid level. The brick colors of structured reds come about from slight addition of oxygen during aging, preferably in a barrel. The bold purple colors of big reds are achieved through thorough maceration, including possible use of macerating enzymes. The hue is influenced by relatively higher pH values.

I like to experiment with my wines, so in some cases I have pushed a wine out of balance on purpose (and then suffered the consequences). I grow Chardonnay and Pinot Noir on a 1⁄3-acre (0.13-ha) hobby vineyard in Sonoma County, California. I have a cool climate with lots of fog, so my harvest tends to come late, sugar levels are sometimes a bit low, and acid levels are typically high. As long as I respect that, I can usually make well-balanced wine; the Chardonnay (in spite of the variety) comes out more in the “light, refreshing” style than “full bodied.” One year, trying to change my style, I chemically deacidified my Chardonnay juice with potassium bicarbonate and fermented it in a new American oak barrel. The wine was not well balanced with the bright fruit character and citrusy notes fighting the oak barrel tannins. That convinced me to avoid straying too far from what the terroir presents.

A Complex Balance

While this discussion has been all about balance, do not neglect complexity. If a wine is so balanced that it presents as bland, the result is disappointing. If you want a particular characteristic to be obvious — alcohol, tannin, sweetness — give it a try. There are strong traditions all over the world favoring balanced wines, however. Whatever you choose, decide what kind of wine you want to make when you start with your source of fruit or must. Develop a vision for your wine, keeping the inherent characteristics in mind. Will you be trying for light and crisp or bold and fruity? Do you want a medium-bodied table red, or a fruit-bomb blockbuster? Apply tools and techniques in service to your vision. Whatever you want to achieve, strive to make sure all of your features serve that same end and always in balance.