The first time judging at the California State Fair Home Winemaker competition, Leah’s group of judges had the rosé category. She recalls the other judges commenting how many of the rosés were not “pink” and therefore must be oxidized and judged them accordingly. Despite her rebuttal on this stereotypical thought, she was just one of three judges. Since then, rosés continue to be embraced by consumers, produced globally in various ways, and it is reassuring to share that wine judges better understand that there is no one specific color for a rosé.

The colors of rosés are based on several factors. The simplistic one is that different grape varieties impart their individual hues during maceration. Rosados from Rioja, Spain, are made most typically with Tempranillo or Garnacha, two of the prominent red grapes (garnet/brick in color) from that region. Same with Italian rosatos made from Sangiovese that all hold a copper tint that can be confused with oxidation as they are not pink.

A rosé can be a slight hint of pink, pink, Barbie pink, have a hint of copper, and everywhere in between. A copper color is not necessarily oxidation. One of the most popular and highly rated rosés imported from France has a slightly copper hue, further showing that color isn’t necessarily indicative for flavor.

Experts will state that some of the world’s best rosés come from France. It may be the Tavel from southern Rhône, or a rosé from Provence, France. Both regions have French wine laws that dictate what grapes are to be used. Laws do not dictate what color they should be. The Tavel is a dry rosé, higher in alcohol, and is made from Grenache and blended with any selection of nine other grapes. Provence is known for making rosés out of Grenache, Cinsault, Syrah, and the white grape Rolle (Vermentino) and can sometimes be off-dry. Again, these are mostly garnet-hued red grapes. Thank goodness few of us live in France and have to follow such winemaking laws.

Let’s not get away from what is truly important; how a rosé tastes. Textbooks agree that a rosé should be light (in body and color), fruity, and refreshingly crisp. Crispness results from a balance of alcohol, sugar, and high acidity. Again, there is no mention of color shade with the exception of its name. Rosés can be sparkling or still, with dry, off-dry, and even sweet characteristics.

So how can rosés be made with a color hue in mind and still meet the textbook definition of a rosé? We explore this question after having entered nine different rosés in multiple competitions over the years. Comments these rosés often received were regarding its color (usually too much) leading to assumptions of oxidation due to a copper or garnet tint. As is demonstrated through numerous experiments we have conducted, and will describe later, the single goal of achieving pale and/or pink color can disrupt the balance of the wine. The same goes for the natural characteristics of some grape varieties used in making a rosé. Some red grapes with higher tannins might be thought of as oxidized. That is not always the case, but increased tannins might mar the rosé’s intent of flavor in regard to crispness.

Our Past Experiences

2017 was our very first rosé from our estate-grown Barbera. Using our own grapes allows us to have more say in harvest times for Brix and acidity. In this harvest, vineyard yields were extremely low, predominantly because of bird damage. As described in a previous article, “When Grapes Throw You For A Curve” (from the August-September 2022 issue), we pivoted from original plans for a red wine to making a rosé. The harvest date was selected to have pH about 3.1 to provide crisp acidity and the juice got about four hours of skin contact. Juice from the press went into carboys for fermentation without additional intervention. There was a lot of learning from that experience, which gave us insight and the thought to make rosés with future vintages.

In 2018 our Barbera harvest had a very high yield. We were not intending to make a rosé that year. Because the juice from the crushed grapes immediately had a pretty pinkish hue without any skin maceration, a decision on the fly was made at the crushpad to make a rosé. This would be our first of several vin gris-style rosés with no maceration (meaning a rosé made from red grapes using white winemaking techniques). A portion of the must was taken immediately to the press. The grapes were not harvested optimally for a rosé’s desired acidity, but acidity was adjusted prior to and after fermentation.

With the 2018 rosé being from Barbera, the juice picked up a somewhat copper hue, but it was not oxidized and rather just the color contribution of the Barbera grape itself. The wine remained balanced with wonderful aromas and taste.

2019 was the first year our production methods started to focus on rosé winemaking as if it was a white wine. Once the desired color was obtained from skin contact and pressing occurred, the juice sat overnight in an enclosed container, allowing solids from the juice to settle. After settling, the juice was racked to another container and then a bentonite addition was done to remove proteins. This was followed with another racking before starting fermentation. We also found a way to do a “cold fermentation” to slow fermentation time by placing the carboys in large tubs filled with ice water.

In the 2020–2023 vintages our experimentation with rosé production continued. Cold fermentation capabilities were upgraded by investing in a glycol chiller for our Sauvignon Blanc and rosé production, and these wines are now consistently fermented at 55 °F (13 °C). Year 2022 was especially noteworthy because of the spring freeze that drastically reduced yields throughout the vineyard. Original red wine production plans were modified resulting in a rosé out of what little Grenache was harvested.

It should be noted that all of our rosés are done “dry,” with no residual sugar. Despite choosing a harvest date for our rosés that optimizes acidity and lower alcohol levels, total acidity is always checked and adjusted prior to and after fermentation. We have also found that color extraction varies from year-to-year and by each varietal as you can see in the photo to the left. Color extraction is monitored periodically during the soak time before pressing. Getting the desired color extraction always seems to be a challenge.

Our 2024 Rosé Project

As we entered our 2024 harvest, we had nine rosé wines under our belts from preceding years. Unsatisfying wine competition results in the past have not left us discouraged and many compliments from others affirm our desire to explore rosé production.

So this past harvest our aim was to harvest Barbera specifically for a rosé. A date was chosen to optimize the appropriate acidity and sugar/alcohol levels. However, harvest decisions can be difficult when labor constraints and temperatures affect the final harvest date. An end of season heat wave drove the Brix up and drove our help away. Brix was a bit higher than desired and titratable acidity (TA) was a bit lower. Acidity was adjusted prior to and after fermentation, ending with TA of 7.3 g/L. Great for a rosé!

Harvest numbers were as follows:

Harvest Date: 9/28/2024

Brix: 26

pH: 3.42 (before fermentation) and 3.5 (after fermentation and adjustments)

TA: 6.4 g/L (before fermentation) and 7.3 g/L (after fermentation and adjustments)

Yeast: D21

Fermentation Length: 38 days at 55 °F (13 °C)

Since we are always interested in trying something new, it was decided to expand this year’s efforts by experimenting with three different rosés and evaluating the results through bench trials. The three were:

1. The baseline single-varietal Barbera rosé

2. Barbera blended with our Sauvignon Blanc to adjust color and add sensory complexity

3. Sauvignon Blanc blended with three different red varietals to add color and sensory complexity

The Baseline Barbera

To get the desired color extraction the juice sat on the skins for three hours. The juice color was checked periodically using a white plastic colander. Pressing the colander into the must allows just the juice to collect inside the colander to be extracted and analyzed. What we’ve found from our experience is that juice from the top of the must will be much lighter in color than the juice from lower in the bin. Once you start pressing the must, the juice color gets even darker. We’ve also learned that maceration time for a desired color extraction varies by varietal due to skin thickness and pigmentation.

At the time of this evaluation the wines have gone through two levels of filtering to create a clear and vibrant looking wine. The wine has also been heat stabilized from fining with bentonite, which is required for a CMC (carboxymethylcellulose) addition for cold stabilization. Prior to bottling, the wine will be sterile filtered and cold stabilized with the addition of the CMC product (e.g., Celstab).

The sensory aspects of the baseline Barbera rosé are great for our desires of a rosé. It has a good, pronounced and clean nose. Medium-plus acid provides for a crescendo of crispness and flavor, making a very refreshing wine. The aroma and taste have fresh strawberry notes. Color is a vibrant light strawberry pink. The finish is long and very satisfying.

Trial 1: Barbera/Sauvignon Blanc Blend

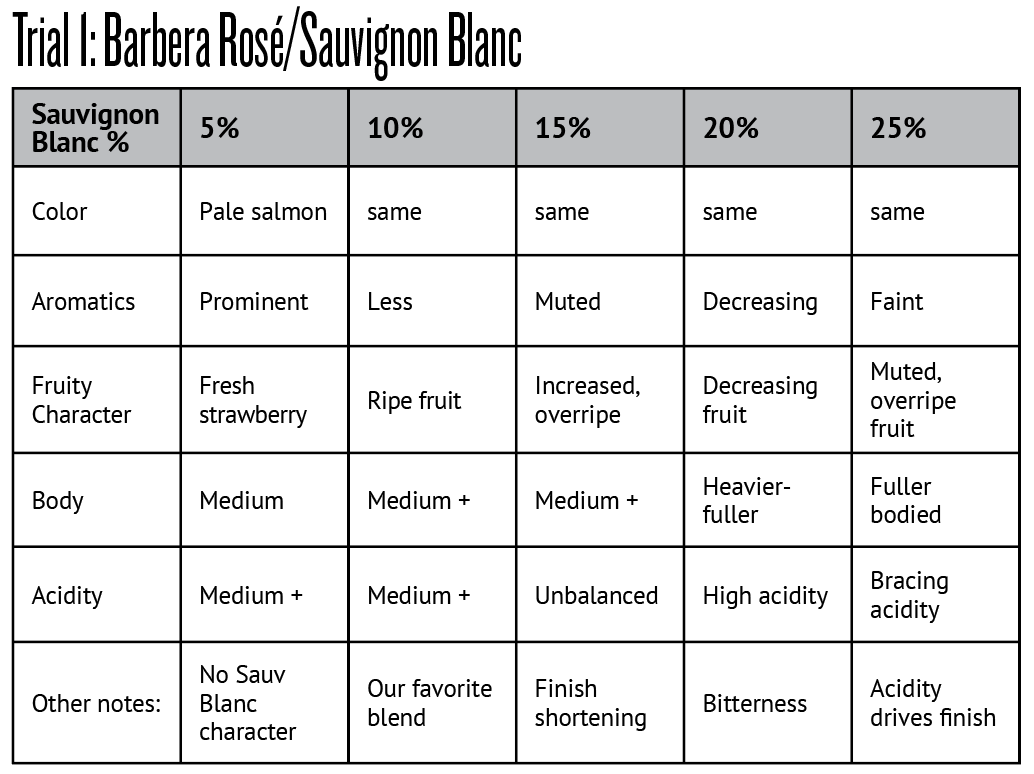

Already having the Barbera rosé, we had the thought that an embellishment with a small amount of our 2024 Sauvignon Blanc would create an interesting and appealing result. The Sauvignon Blanc is very aromatic and has great acidity, so in theory it could work well. The question is how much of the Sauvignon Blanc to use? Therefore a bench trial was conducted using different percentages of the Sauvignon Blanc added to the Barbera rosé.

From a sensory aspect, the Sauvignon Blanc had a long, cold fermentation and was left on the secondary lees to increase mouthfeel. Total acidity is very similar to the Barbera rosé, but the sensory level of acidity is slightly less and more in balance. Aroma and taste have apple, pear, and white peach characteristics. The finish is long with a slight note of phenolic bitterness.

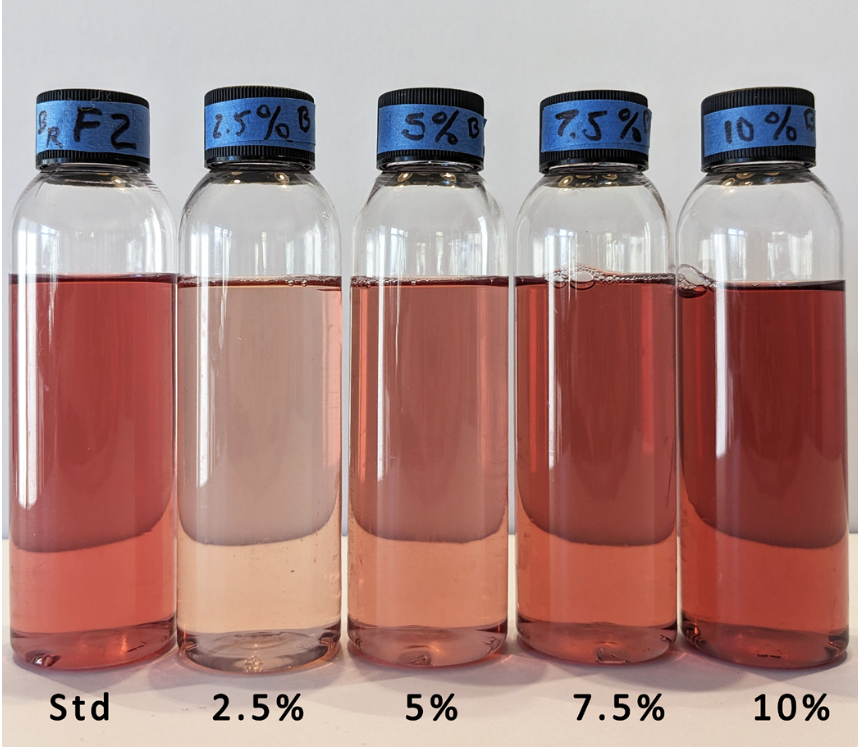

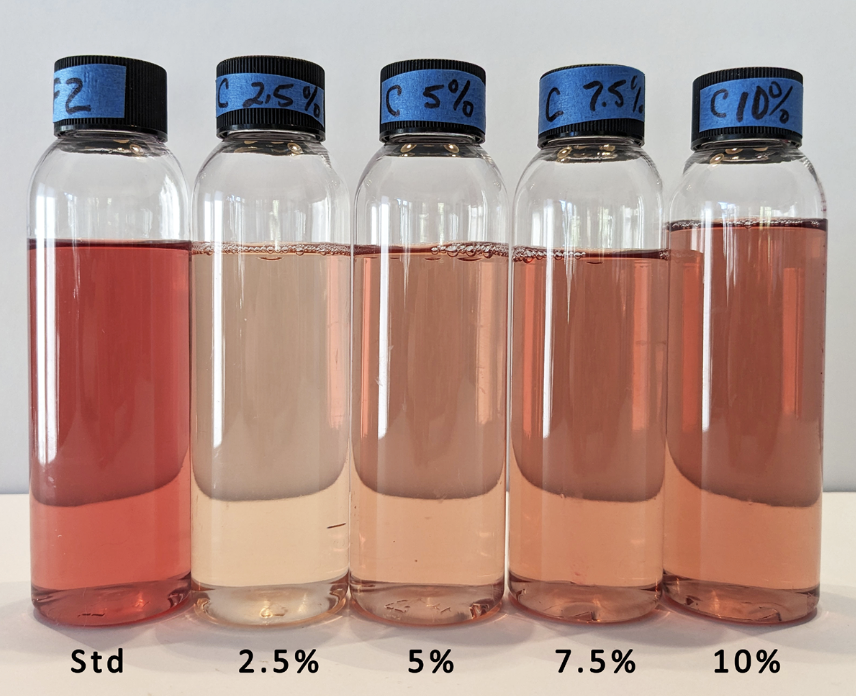

Once the blends were created and placed in 125-mL laboratory sample containers, tasting samples were poured into wine glasses for sensory evaluation and comparisons. This same method was done with all trials. In all of the trials and sample pictures, the baseline standard (Std) Barbera rosé is on the left to compare color with the trial blends.

As you can see in the Trial 1 photo, even up to a 25% Sauvignon Blanc addition resulted in a minimal change in color. However, other sensory characteristics suffered a much more significant impact. As noted in the Trial 1 table, above, the fresh strawberry character of the 100% Barbera became more convoluted as the Sauvignon Blanc additions increased. Despite the Sauvignon Blanc having good acidity, it caused the blend to become flabby and lose its brightness. Although the 10% blend was the preferred blend, the base Barbera was by far the best and most balanced wine.

The “White Wine” Approach to Rosé

Many commercial wineries make rosé wines starting with one or more red varieties that are processed without any skin contact, therefore creating what is in essence a “white (colorless) wine.” As in Tavel and Provence (and other regions), winemakers may start with a red wine base like Grenache. Grape clusters go directly to the press as a whole cluster press or are immediately crushed and then go directly into the press with no skin maceration. After fermentation, a small amount of a red wine is blended with the “white” base wine to produce the desired rosé color characteristic.

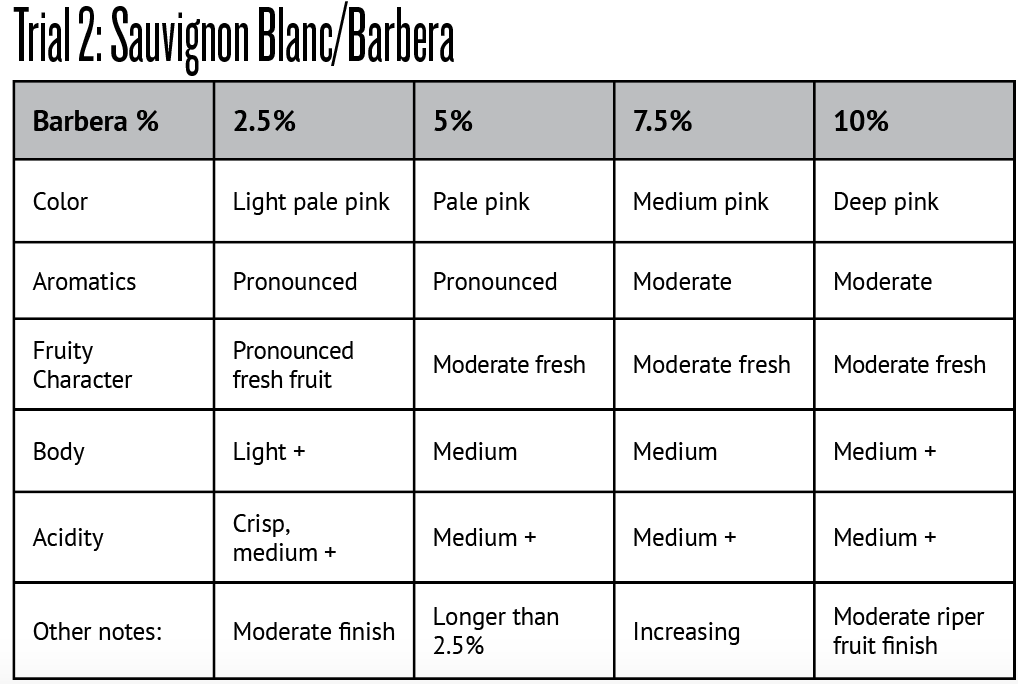

We took a similar approach in this rosé bench trial by using our 2024 Sauvignon Blanc as the base wine and then blending that with a small amount of red wine. To extend our experimentation, we decided to trial the use of Barbera, Petite Sirah, and the French-American hybrid Chambourcin as separate blending components so each may add their own distinct characteristics and color.

Trial 2: Sauvignon Blanc/Barbera

As you can see in the above photo, with the baseline Barbera rosé on the left for comparison, a 7.5% addition resulted in a similar level of color, but with a slightly different hue. The 2.5% was more aromatic, but the 7.5% had a more enjoyable taste as the acid was balanced.

The 7.5% blend was our favorite of this group in its sensory evaluation due to more fruit flavors picked up, but the baseline Barbera rosé was still preferred because it better meets the classic definition of a rosé and was more to our liking. The 7.5% blend’s color was a clear medium pink with a slight copper tint. It had a moderate intensity aroma of light watermelon, light strawberry, hint of peach, and hint of fuji apple, along with flavors of watermelon and peach. The finish of this blend was also lengthened with a medium mouthfeel.

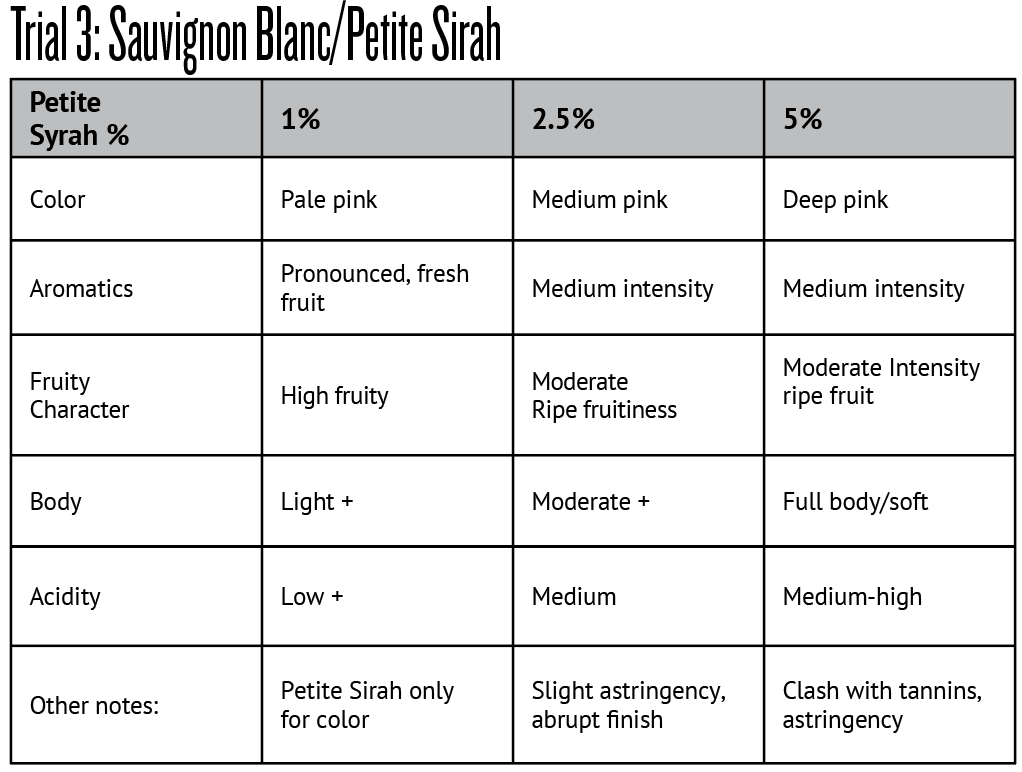

Trial 3: Sauvignon Blanc/Petite Sirah

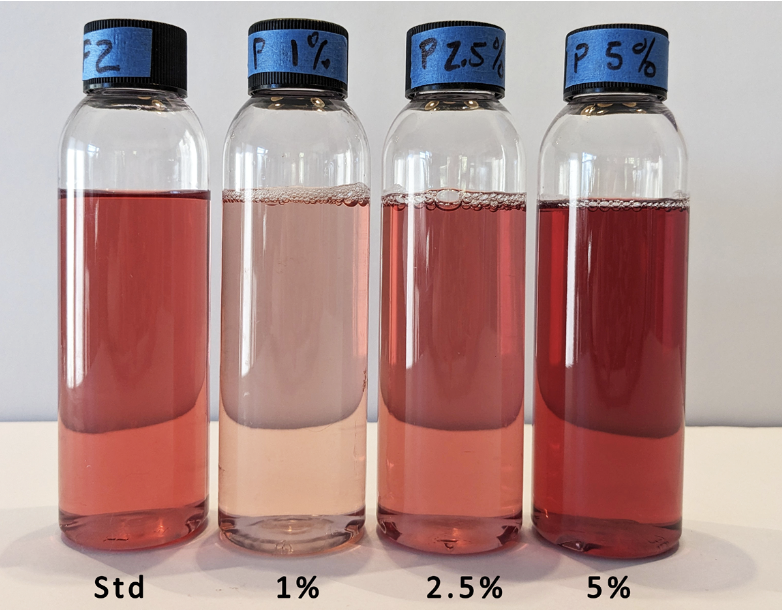

Petite Sirah was chosen not only because we grow it, but because its color contribution is quite pinkish vs. other garnet-colored varietals. Petite Sirah is a common variety to add color (and tannins) to other red wines as well as rosé. Because Petite Sirah has very pronounced pigmentation, the percentages of the blend trial were much lower than the other varieties to produce a light pink hue.

The 1% addition merely added color to the base Sauvignon Blanc with no other sensory impact. The 2.5% addition was our favorite of the three blend variations, but the increase in astringency and its abrupt finish made it overall a second choice to the baseline Barbera rosé.

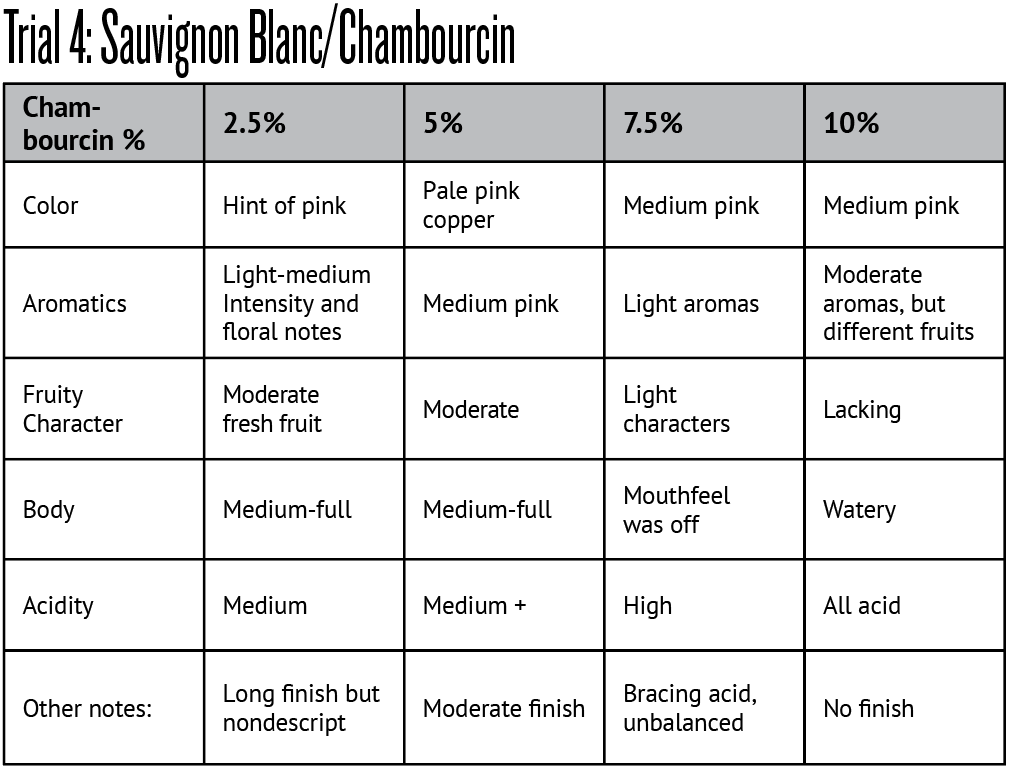

Trial 4: Sauvignon Blanc/Chambourcin

On the East Coast, native grape Cynthiana/Norton and hybrid grape Chambourcin are popular red grape varieties used for rosé production. We therefore purchased a bottle of Johnson Estate’s 2020 Freelings Creek Reserve Chambourcin to add color and sensory components to this blend. The Chambourcin wine was an off-dry, red with 13% ABV from the Lake Erie region of New York State. A beautiful “pink” rosé made from a 70+% Chambourcin and blended with Vidal Blanc and Traminette from JoLo Winery and Vineyard of North Carolina was used to make sensory comparisons to the blends created here.

As you can see in the Trial 4 photo, Chambourcin, being a lighter pigmented varietal, contributed much less color than the Barbera and Petite Sirah. In theory, this should allow more of the varietal characteristics to come forward without getting the rosé too dark. However, as we found out from our trial, the Chambourcin was not complementary to our Sauvignon Blanc. It produced a nice color, but the finish became nondescript, and its residual sugar and acidity was unbalanced, which masked the fruit characteristics.

In Conclusion

Out of all these sensory trials, ultimately our preference was the original baseline Barbera rosé. Its pale strawberry color was dazzling, the acidity crisp and energized with a nice mouthfeel, and it had a long and satisfying finish. In addition, with the use of the Barbera varietal, the contributing characteristics allow the wine to be enjoyed on its own, but it also stands up well with many foods.

A lot was learned by going through this experiment and we are excited for our 2025 vintage to revisit our estate Grenache to produce another rosé.