Grape Profiles

Here are some abbreviated profiles for lesser-known wine grape varietals:

Aglianico:

Considered by some to be one of the three great red wine grapes of Italy (along with Sangiovese and Nebbiolo), this ancient wine grape was highly regarded among Romans and is mentioned in the writings of Pliny the Elder. Its name in those times was Elenico, meaning Greek, which indicates that its origins are from across the Adriatic Sea and date well beyond the rise of Julius Caesar and the Roman Empire. Nowadays its most well-known home lies in the Tuarasi DOCG in the Campari region of Italy — just north of the boot on the western shores of the Mediterranean Sea — but finds success in a few other regions of the world as well.

Aglianico appreciates especially dry and sunny climates as it is late ripening. In its homeland the wines are often full-bodied and highly tannic due to its thick skin. This polyphenolic load often needs several years aging to bring balance to the palate. But there are many New World examples of Aglianico coming out of places like the Central Valley and Paso Robles regions of California that have depth and complexity without the need for a long cellaring period to bring that balance. While its acreage here in North America is quite small and limited to just a handful of places in California and Texas, there is reason to give this grape a try, whether you find it available from a grape grower or when establishing a vineyard in a dry and sunny microclimate.

Airén

Up until 2004 it held the title as the world’s most-grown wine grape variety. It still sits at the number four spot today, currently found just behind Tempranillo. Also, it does still hold the title of most-grown white grape variety in the world. So why is it that most wine enthusiasts have never heard of Airén grapes or wines before? Simply put, most of the wine produced from the variety gets further processed, via distillation, into brandy. When it does get included in table wines, it’s often blended in anonymously.

Almost exclusively found in central Spain, its strong drought- and disease-resistance as well as very low nutrient demands make it easy for farmers to tend to, hence its popularity. It’s traditionally head-pruned and allowed to grow like bushes in very low-density plantings. But its resulting low acidity and rather lackluster fruit character has meant that it’s best blended to make a more balanced wine (or distilled into brandy). For those who are willing to search, some varietal wines are now out there as the focus on viticultural practices by some farmers are increasing fruit-cluster quality to highlight its best features. In the winery, lees contact can be used to really help lift the wine as well.

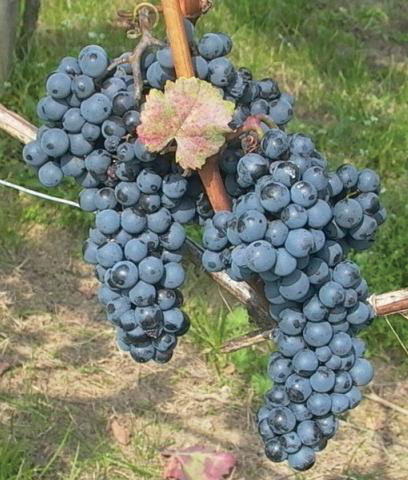

Baco Noir:

A hybrid red grape varietal whose parentage is linked to the French grape Folle Blanche, a white Vitis vinifera varietal, and a native American red V. riparia grape. This hybrid grape variety originated in southwestern France by a gentleman named François Baco in 1902 and was released in 1910. Originally developed for brandy production (hence the Folle Blanche parent), it was found to be resistant to Black Rot. This variety was not sanctioned in France under the Appellation d’Originie Contrôllée (AOC) but it is tolerated so it’s still grown in France and Switzerland, about 300 acres in total. When it was brought over to North America, it found a home in the cooler climates and loamy soils found in the eastern United States.

Often known for producing Rhône-style wines, it can be blended into Bordeaux-style wines. Alternatively, a winemaker can try to shorten maceration time to get a more Burgundian-style wine and coax out its berry and cherry characteristics. It is a consistent mid-season ripening grape with low tannins and high acidity. Patience is required to get a higher-Brix, lower-acidity Baco Noir grape. An acid reduction regime may be required if total acidity (TA) comes in above 1.2. Warm fermentations can also really help express the berry fruit characteristics of this grape.

Baco Noir is a great hybrid great for blending as it provides bright color and cherry/berry flavors, but often needs tannins. Just be sure to perform a proper must analysis prior to fermentation to make appropriate TA or sugar adjustments as needed. To learn more about Baco Noir or other cool climate grapes, we recommend the book Grapes of the Hudson Valley and Other Cool Climate Regions.

Blaufränkisch:

A grape of many names, Blaufränkisch is one of the most widely planted dark-berried varieties of Austria due to its high acidity, good color extraction, and rich tannins. This black grape most widely planted in Austria’s Burgenland, where most of the nation’s 7,500 acres grow. It is also popular in other central European countries, especially Czech Republic where it is known as Frankovka, and Germany, where it is known as Lemberger. In the United States, it is most widely grown in Washington State, however its popularity has dwindled over the past decade and less than 100 acres are now growing in the Evergreen State, where it is also known as Lemberger. Blaufränkisch was for a long time mistaken to be the Beaujolais grape Gamay, and Bulgarians still call it Gamé. In 2010 there were 40,000 acres planted worldwide, making it the 48th most widely planted grape, according to The University of Adelaide. The grape is believed to have been around since the Middle Ages with a parentage of Gouais Blanc and an unidentified Frankish variety.

Blaufränkisch is an early budding variety, which makes it susceptible to early spring frost. It is also late ripening and therefore does best in warmer climates, however it handles the cold winters common to Washington and the Finger Lakes region of New York. It is known to produce high yields of up to 5,000 tons per acre, and more in some parts of Europe.

In winemaking, it is often treated similarly to Syrah and aged in new oak, as is common in Austria. Elsewhere it is treated differently, for instance in Slovakia it produces lively, fruity, vigorous wines for early consumption and in Germany it is often blended with Trollinger to produce a light red wine for quick consumption. In northern Italy in Friuli, the grape is called Franconia Nera and makes fruit-forward wines with high acidity. It is also used to add fruit notes to Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon in various regions.

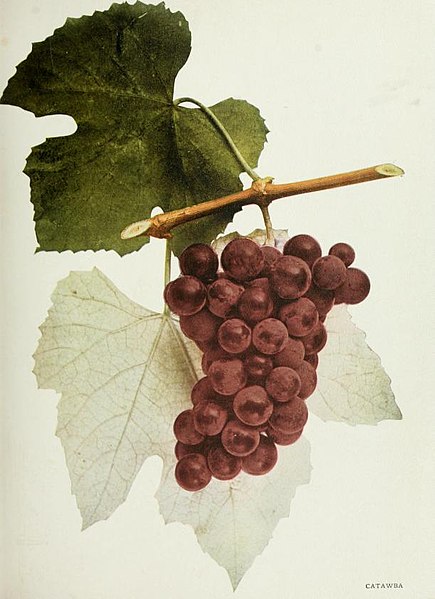

Catawba:

After reading through Chik Brenneman’s “Varietal Focus” piece regarding Concord grapes, there was inspiration to investigate more on this grape.

The exact origins of Catawba are unknown to us at this time, but it is generally considered to have been first grown in the southern mid-Atlantic states, though western North Carolina is often cited as the area it arose. It was one of the first grapes in North America to be used for wine production as most Vitis vinifera varieties struggled with fungal pressures due to humidity found in the climate of the eastern US. The name originates from the native people that populated that region of the Carolinas and the Catawba River there, reaffirming the idea of origins from that area.

The Catawba grape is a cross between the native North American V. lubrusca and the V. vinifera Sémillon grape variety made famous in the Bordeaux region of France. From the early- to mid-19th century Catawba was the most widely planted grape on the North American continent. And the first successful American winery was a Catawba winery along the banks of the Ohio River.

Just as with all labrusca grapes, the foxy-musty quality is found in Catawba wines but at a low level. Its light-colored skin is due to low levels of anthocyanins and phenols and make it nearly impossible to produce a red wine from Catawba. It’s a late-harvesting grape with moderate acidity. Most Catawba wines either fall into the white or rosé categories despite the red-looking grapes. Catawba can still be found scattered throughout the eastern US, but its prevalence has waned due to the more recent French-American hybrids.

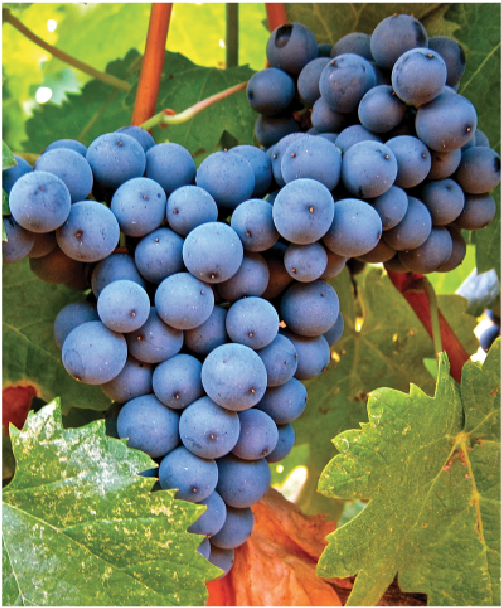

Chancellor:

For those living in cold-climate regions, Chancellor is one red grape varietal that should not be overlooked. Up until the 1970s this French-American hybrid grape varietal was simply known as Siebel 7053 despite having been developed in the 1860s by French grape-breeder Albert Siebel. At one time, this grape variety was one of the most widely-planted hybrids in France, but it didn’t reach the commercial success like some of its siblings. The grape made its ways across the Atlantic in the 1940s and has since found a home in well-ventilated vineyards throughout the central and eastern US.

Chancellor is very well-regarded in terms of the quality of wine it can produce, but it’s in the vineyard where this grape variety may have some struggles. Being highly susceptible to powdery and downy mildew means that grape growers need to be especially diligent about their spray protocol, most notably in the early part of the season through flower set. Early budding means that it is susceptible to frost damage as well. Thinning of the fruit clusters is also a well-known task required for success with Chancellor. But if the harvest goes well, there are few other French-American hybrids that are more highly regarded for the quality of wine it produces.

Expect a medium-body wine with an elegant but fruity nose. Blueberry, plum, raisin, cranberry, and fig aromas are often cited on well-made versions. Acid levels tend to be moderate. Many winemakers like to blend Chancellor with Bordeaux-style grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, or Merlot. If you know a vineyard that grows Chancellor or have a well-ventilated vineyard in a cool climate, you may want to give this grape a try.

Colombard:

Colombard, a white French grape variety, makes wine that is commonly drank, yet rarely recognized. It is crossbred from Gouais Blanc and Chenin Blanc, and it shows up as a base in many white wine blends. Colombard is planted widely in California, South Africa, and its birthplace, Gascony, France. Until Chardonnay took over in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Colombard was the most planted grape in all of California. In the 1970s the French decided to rip up a lot of the Colombard vines in order to make room for more fashionable grape vines. During this time period, Colombard was mainly used for the production of brandy.

In South Africa, it is known as “Colombar.” Its ability to grow in dry, hot climates makes South Africa and California great places to grow it. Not only is Colombard resilient in hot climates, but it also refuses to become extinct, deeming this grape one of the toughest grapes out there.

Colombard production of wine is limited to crisp white wines only when properly cultivated. It is known to be a light white wine resulting in a dry taste. Colombard gains lots of natural acidity during the cultivation process. Today, Colombard is used as a blending grape for table wines. Notable wines that Colombard blends well with are Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc, Riesling, Sauvignon blanc, Sémillon, and Syrah (similar to how Viognier is sometimes blended with the red Syrah grape, a practice that began in northern Rhône). At the peak of ripeness, Colombard is capable of producing fruity flavors and aromas like peach, melon, apple, tropical fruit, and hints of spice. Less than ripe Colombard may result in neutral flavors such as boxwood, asparagus, and rhubarb. If and when you are looking for a bottle of white wine to drink such as Chardonnay or some bubbly, remember that there is most likely a Colombard base in your bottle.

Edelweiss

A cold-hardy grape varietal developed by Elmer Swenson and released with the cooperation of the University of Minnesota, this white grape varietal is a hybrid cross between a Vitis riparia (Minnesota 78) and a Vitis labrusca (Ontario). Susceptible to powdery mildew, a regimented spray program will be needed to keep the vines happy and healthy. Edelweiss can be planted in climates down to USDA hardiness zone 4, which is as cold as -30 °F (-34 °C). Heavy winter mulching is recommended in these colder zones though. Harvest should happen fairly early in the ripening process, as fruit left hanging will produce the often-maligned “foxy” quality inherent in many non-vinifera grape varietals.

Edelweiss grapes will usually be brought in between 14–16 °Brix and can often exceed 1% total acidity (TA). Chaptalization should be performed to bring the Brix up to roughly 22 and an acid reducing yeast strain like Lalvin 71B-1122 should be used with a high acid must. If, after fermentation is complete, TA still is above 0.8% potassium carbonate may be added. Malolactic fermentation is not recommended as the process can interfere with aromatic qualities of the wine. Wines produced from Edelweiss grapes are frequently backsweetened some in order to balance out the high acidity. Make sure to use sorbate if you plan to backsweeten. When a fine example is produced, notes of pineapple, pear, honey, and peach are common characteristics cited in the profile.

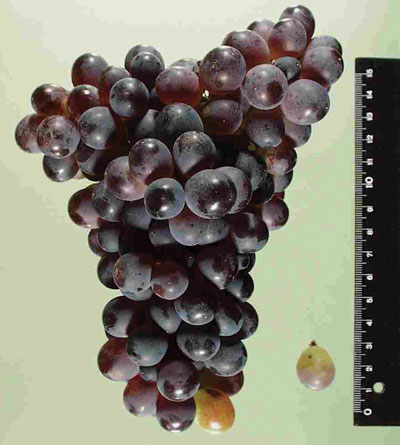

Frontenac Noir:

A hybrid variety released in 1996, Frontenac was the University of Minnesota’s first licensed grape variety. It is a cross between the hybrid Landot Noir and the native North American Vitis riparia, a grape species known for its strong cold tolerance. Frontenac has three distinct varieties in the family: Frontenac Blanc, Frontenac Gris, and Frontenac Noir. The Noir version can be utilized for reds, rosé, and Ports.

In the vineyard, the vines are well known to be highly vigorous, very cold hardy (USDA zones 4a–7), resistant to powdery mildew and Botrytis, and highly resistant to downy mildew. Frontenac’s large loose clusters allow enough air movement to avoid issues such as bunch rot and cracked berries. The grapes themselves can be highly acidic. Harvest of this variety often occurs between late-August to mid-September, but later harvest is often recommended to help bring acidity levels down.

Winemakers should be ready to tackle the acidic nature of Frontenac wines. Having ripe grapes come in at pH 2.9 and titratable acidity at 15 g/L is not unusual. Malolactic fermentation is highly recommended, and if TA is still high, potassium bicarbonate can be added to counter the low pH. Well-made examples of Frontenac Noir will often have a beautiful cherry bouquet with hints of plum, black currant, and chocolate in the background. For those living in cold climates, this is a great grape to grow but can be a challenge in the winery when pH and TA are on the extreme end.

Glera:

For fans of Prosecco wines, the Glera varietal of grapes may be familiar to you already. But for everyone else unfamiliar with this white wine grape varietal, you may be surprised to hear it is actually one of the most planted wine grapes in Italy. For a long time, this grape varietal was more commonly known as Prosecco, based on the town where it is thought to have originated in northeastern Italy. But when the region submitted their request for Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status, to avoid misrepresentation by wine producers, the grape varietal and style of wine needed to be bifurcated. Glera was an already known name, so in 2009 this name was officially sanctioned.

This low-acidity grape allows the carbonation from Metodo Italiano (aka Charmot method) to brighten up the flavors on the palate. Glera is also known as a fairly neutral grape with lower handling and special needs, allowing the price of Prosecco style wines to often be on the more affordable side.

Graciano:

Primarily known for its use in the Grand Reservas of the Rioja and Navarra regions of Spain, this deeply-pigmented grape appreciates warm and dry climates. Graciano can also be found growing in Australia, France’s Languedoc region, Argentina, and in California. It can go by the name of Xeres, Graciana, Morrastel, or Courouillade and is most often used in red wine blends, but can sometimes be found as a varietal wine as well. In the vineyard, Graciano is prone to disease, downey mildew in particular, and is a low-yielding vine but can produce highly aromatic wines with nice structure that can age gracefully. Some folks compare Graciano to Cabernet Sauvignon in its structure.

Its late ripening and high acidity means that warmer climates are required. One story goes that Graciano is named for the response a vineyard manager gave to a request to grow the grape, “Gracias, no.” Only about 2,450 acres (990 hectacres) remain of the grape in its native region of Spain, but due to the wines it can produce, we can be sure it won’t disappear. A few select California vineyards, especially in the Lodi region, are finding just how charming Graciano wines can be.

Maréchal Foch:

Maréchal Foch is a red French hybrid with a parentage of a riparia-rupestris cross, and the vinifera variety Goldriesling. It is most well known for its ability to thrive in climates too cold for vinifera varieties to survive. Maréchal Foch can withstand freezing temperatures down to -20 °F (-29 °C) for extended periods of time. This makes it a popular grape in north eastern areas of the United States and Canada, however it is also sporadically grown in parts of Oregon and Canada’s Okanagan Valley. Though it can withstand freezing temperatures, Maréchal Foch is vulnerable to mildew in some areas due to its tight clusters of small berries. Mildew diseases can result in significant loss of crops, so Foch growers often rely on strict spraying routines.

Maréchal Foch ripens early in the season, and is ready for picking within 80 to 90 days after budbreak. Cold temperatures and early harvesting can lead to lack of sugar content and high levels of acid. On average Maréchal Foch planted in cold areas have a Brix of about 15 to 18. This forces winemakers to add sugar before fermentation to bring the Brix up to the appropriate 20 to 23 range. Acid levels in Foch are typically high around 1.0 percent. The acid levels should generally be in the 0.6 to 0.9 percent ranges. Picking early is common for Foch because it ripens early, and factors like predators or frost can force growers to pick early for protection. However, the longer the grape stays on the vine, the more sugar levels it will gain, so holding out until that first frost is forecasted often results in the best grapes for wine.

Maréchal Foch grapes are most often made into dry table wines, but some winemakers also use it to make a fortified Port-style wine. The wines often have a gamey nose and the foxy characteristics often described in hybrids.

Marquette:

First introduced by the University of Minnesota, Marquette is a cold-hardy red wine grape that can withstand winter temperatures as low as -30 °F (-34 °C). Its parentage is a cross between two other hybrid grapes and is best known for producing dry, medium-bodied reds with the capacity to get Brix up to 22–26. According to the University of Minnesota, the suggested titratable acidity at harvest is roughly 11–12 g/L and a pH between 2.9–3.3. The wines it can produce are well known to be able to stand up to an extended time in barrel.

In the vineyard, Marquette has a reputation for its disease resistance with moderate resistance to black rot, Botrytis bunch rot, and both powdery and downy mildews. But it does have some susceptibility to phylloxera. It is an early budding vine, which makes it vulnerable to late frosts. It is a later ripening variety, sometimes hanging on the vines until late September or early October. Marquette is a vigorous grower, making it well suited for soils with lower nutrient levels. High-nutrient soils will require greater spacing in order to allow the vines to spread, and an aggressive canopy management may be needed in that circumstance.

Because of the quality of wine it can produce, Ontario, Canada, added Marquette to its list of approved grapes under its VQA label in 2019. For those living in colder climates and looking to grow wine grapes, Marquette should be near the top of your list of varieties to investigate.

Meunier:

Meunier, or Pinot Meunier as it is often referred, is most widely planted in the Champagne region of France, and is one of the three grapes permitted in Champagne wine production. Meunier is a red (some may say black) grape variety that has higher acid levels and is lower in tannins than Pinot Noir. In Champagne wines, it is used to contribute a fruitiness and acidity to complement Pinot Noir’s weight and Chardonnay’s finesse. Meunier accounts for approximately 40 percent of the vineyards in Champagne, however in Champagne blends it is often just used as 10–20 percent of the blend. This is partly because it is not known to age well. As an interesting side note, while most Champagne production includes Meunier, Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir, perhaps the most famous Champagne, Dom Pérignon, is one of the few that do not include Meunier in their bubbly.

The name Meunier is French for “miller,” and was given to the grape because the underside of its leaves have fine white “hairs” that give it the appears of having been dusted with flour. In the vineyard it grows in compact bunches, which makes it susceptible to rot. The vines are ideal for colder climates because they bud later and ripen earlier than Pinot Noir. This shorter growing season makes it more dependable to produce a predictable harvest even in years the climate can wreak havoc on other vines.

For many years, Meunier was thought to be a clone of Pinot Noir, however DNA tests at UC-Davis in the 1990s determined it to have a parentage of Gouais Blanc and a Pinot prototype.

Even outside of Champagne, Meunier is most often used as a component for sparkling wine production, including in Germany (where it is known as Müllerrebe or Schwarzriesling), North America, and Australia.

Mustang:

Mustang grapes have been used for generations to make wine. A native American grape species, Vitis mustangensis, is typically found growing wild on fence rows across parts of the southern US and northeastern Mexico. Its range spans from central Texas in the west to Alabama in the east, north to Oklahoma and Arkansas and south into northern Mexico. Mustang grapes are not actually a grape that a person would eat as the acidity levels can be high enough to burn or irritate a human’s mouth. Even handling Mustang grapes, winemakers are recommended to wear gloves to prevent irritation due to their corrosive nature. Acid test kits that winemakers typically use may not even go high enough with some Mustang grapes to get a true reading of their acidity. A full titration setup may be required. But with a little care, the juice can be transformed into an interesting and enjoyable wine.

Mustang grapes can begin to ripen by late June, although the grapes can hang all the way until fall in some cooler locales such as the Texas Hill Country. It is important to try to harvest at the correct time. Mustang can be made either into a blush wine if you press quickly or into a red wine if fermented on the skins. These are a slip-skin grape variety, so white wines could also be attained by removing the skins. Chaptalization will be needed as Mustang grapes are notoriously low in Brix when ripe. But the grape skins of this species have been known to contain plenty of character, so this can be a fun avenue to explore for winemakers in regions where Mustang grapes are found.

Niagara:

Niagara is a white hybrid Vitis lubrusca grape created in 1866 in Niagara, New York through a cross breeding of Concord and Cassady grapes. Niagara is a sweet juice grape, which is likely why it is most commonly known as the base of most grape juices. While it is most widely grown for its value as grape juice and to be eaten as a table grape or made into jam, many winemakers are also using Niagara to make varietal and white blended wines as it is widely available and inexpensive. For winemaking, Niagara grapes are known for their low acidity, requiring the winemaker to balance the acidity in the winemaking process. From there, Niagara can be made into a variety of wine styles from off-dry (probably the most common) to sweet, and even in styles like Sherry or sparkling wine.

The Niagara vine is productive, vigorous, and can survive in low temperatures. Its success growing in the cold climates has deemed the Niagara grape the most successful native white grape in the state of New York. Though Niagara can thrive in cold temperatures, it also does well in warmer climates, illustrated by the fact that it is the most widely planted white wine grape in Brazil as well.

Niagara begins to ripen about midway through the season and is often an early harvest. It is a bad shipping grape however, meaning that the grape only does well around the area in which it grew. Niagara-based wine is said to have the “foxy” character so often used to describe native American hybrids, which can be undesirable to drinkers. However, at the low price point, it’s a fun grape to experiment with in the bottle, while enjoying a handful at the table.

Negroamaro:

A popular grape native to Italy’s “boot heel,” more specifically the southern Puglia region of Italy, Negroamaro means “black” and “bitter” in Italian. Folks in North America are much more familiar with one of this grape’s blending partners, Primitivo, more commonly referred to as Zinfandel. Primitivo though is not actually native to the Puglia region. But unlike Primitivo, Negroamaro has not widely seen success here in North America. There is very limited acreage planted in California (41 acres) and Texas (14 acres), but due to its drought resistance and love of warmer temperatures, don’t be surprised to see more interest in the future. It is considered a fairly neutral grape with notes of dark berry fruit and tobacco. The translated name does not actually apply to the wine which it produces as they are neither black in color nor bitter on the tongue. It does have a nice medium finish. So while Negroamaro is best known as a blending varietal, wines made from the grape are known to produce lush, berry characteristics.

While fresh-grape winemakers may be out of luck sourcing Negroamaro grapes here in North America, kit and juice winemakers should have better access. Keep your eyes out for special releases from kit producers and from importers of Italian juices. Bottle shops with a solid Italian wine section likely have a good selection of commercial wines from Puglia made from Negroamaro grapes. Rosé wines made from Negroamaro are some of the highest regarded expressions of wines made from this grape varietal. If you do try any, might we recommend pairing it with a nice Amaro as a post-dinner digestif.

Palomino:

In southern Spain, the Jerez de la Frontera area is home to 74,000 acres of the white Vitis vinifera variety Palomino. Palomino — or Palomino Fino to distinguish it from its ancestor, Palomino Basto — was named after one of King Alfonso X’s knights. Palomino produces a low-acid, low-sugar grape that oxidizes easily and has perfect raw material for Sherry, the style of wine of which it is the most popular grape.

The grape is able to withstand drought and grows the best in warm, dry soils making Spain a perfect region to grow it. However, the Palomino vine is extremely susceptible to downy mildew, which can affect vine leaves and ultimately harvest quality. Vineyard owners, to prevent downy mildew from ruining their stock or future stock, use pre-infection, and post-infection protective sprays. The Palomino grapes ripen in early September with thin skin and a yellow-green color. It is a juicy grape that is moderately sweet, and the grape itself is quite fragile.

Outside of Spain, Palomino is also heavily planted in South Africa, where it is most commonly used for distilling and the production of value table blends. Other regions where Palomino is grown to a lesser extent include California’s Central Valley (where it is generally used in the production of fortified wines), Chile, Australia, and parts of South America. In the less common practice of using Palomino for a dry table wine, considerable acidification is necessary.

Palomino carries a very neutral aroma, perfect for Sherry, however not ideal when it comes to other wine styles.

Pecorino:

An Italian white grape varietal from the rocky, mountainous terrain found in the Marche and Abruzzo regions of east-central Italy. This grape was in slow decline for a long time due to its lower yield than some varietals, but its popularity has grown in recent decades as the trend towards more flavorful wines has breathed life back to Pecorino with the push for quality over quantity. In 2019 there were over 3,000 acres (1,215 ha) of Pecorino planted in Abruzzo and that number is growing quickly. Varietal wines made from its grapes have been noted to have lemongrass, chamomile, and fresh stone fruit character.

One reason some folks may have never heard of Pecorino before is because there are 45 known synonym names for this variety according to the Vitis International Variety Catalogue (https://www.vivc.de/). The grape is known to be strongly resistant to both powdery and downy mildew. It’s an early ripening varietal that often comes in not only high in sugar but also acidity. This provides a nice balance for winemakers to start with. Wines can be still, sparkling (spumanti), or made into dessert wine (passito). If you find it on your wine store shelf, pick up a bottle. You may find a new go-to white.

Petit Pearl:

Petite Pearl is a dark red hybrid grape bred by Minnesota viticulturist and grape breeder Tom Plocher in 1996 and made available to winegrowers in 2009. Its parentage includes vinifera, riparia, and other genera. The vines are known for their tolerance to extreme cold conditions (surviving winters in which temperatures fell below -32 °F (-36 °C) and disease-resistance. The grapes have thick skins and the clusters are compact and dense. It is late to bud, helping protect it from spring frosts, and typical grape production is 3–4 tons per acre on high cordon trellising.

Petite Pearl produces complex wines with abundant soft tannins, balanced acidity, and none of the foxy flavors and aromas often associated with some other wines produced from Native American or hybrid grapes. The wine is garnet red with typical flavors of clove, star anise, celery seed, and wild mushrooms. It is produced as a varietal wine as well as a blending component to add body, tannins, and softness to highly acidic varieties.

Scuppernong:

Prevalent throughout the southeastern region of the United States, Scuppernong (Vitis rotundifolia) grapes are a native grape to this area and the state fruit of North Carolina. Often confused as the white version of Muscadine, Scuppernong is actually just one of many white grape varieties found in the Muscadine grape family. When the grapes are fully ripened, they should have a deep green to bronze color, with large fruit and a thick, leather-like skin. Because of their thick skin, a proper grape crusher is usually required.

Scuppernong vines will start to die off if temperatures fall below 0 °F (-18 °C), but they are highly disease resistant due to the high levels of polyphenolic antioxidants found in the skin. For these reasons, the grape cultivars commonly associated with Scuppernong are found from Virginia south and west to Texas, a region well-known to be a difficult zone for Vitis vinifera. Popular cultivars include Carlos, Magnolia, Sterling, and Triumph. Don’t try to cross Vitis rotundifolia with other grape species though, as many have found this variety does not cross readily.

The grapes are typically harvested by shaking the vine and the ripe berries will fall to the ground and collected by drop cloth. The ripe Scuppernong grapes should have their skin starting to loosen and typically fall into the range of 18–25 °Brix. Expect around 17–19 lbs. (7.7–8.6 kg) of grapes to produce one gallon (4 L) of must. Chaptalization may be required for lower-Brix grapes or to dilute the juice. Long skin contact time is not recommended, especially if trying to produce a white wine.

Vignoles:

A white hybrid grape varietal whose parentage is currently unknown in a story of mistaken identity. Thought originally to be a cross between a Pinot Noir clone and one of Albert Seibel’s hybridized grapes, genetic testing has shown that the vines now labeled Vignoles are actually from a different line altogether with neither of these two found in its genes. This white grape is grown primarily in a belt stretching from the Hudson Valley region of New York to Pennsylvania through the lower Midwest; including Missouri, Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky.

In the vineyard, Vignoles breaks bud late allowing it to escape most late-spring frost events. On average it is known to take roughly 105 days to get the grape from bloom until harvest. Its thick skin allows some grape growers to leave it hanging long enough to produce ice wines, obtaining upwards of 30 °Brix. Botrytis is a threat with Vignoles, but can also be utilized by the winemaker to obtain a honey-like character in the wine, most notably if going for a Sauternes style of sweet wine.

Vignoles is considered a high-sugar, high-acid hybrid grape. Winemakers will typically need to provide some backsweetening at bottling to counter the acid levels with semi-dry wines being the most common table wine produced from the grape. There are some examples of dry varietal wines being produced. Blending is another common approach to producing wines with Vignoles.