Q

Early this year my Frontenac vineyard at my daughter’s in Waldoboro, Maine became covered with thousands of Japanese beetles, which seemed to eliminate the entire leaf structure. It appears there is no way to eliminate these beetles, unless you have the answer? Incidentally, the grapes seemed to survive somewhat, yet they tasted sour.

Edwin Kaarela

Westminster, Massachusetts

A

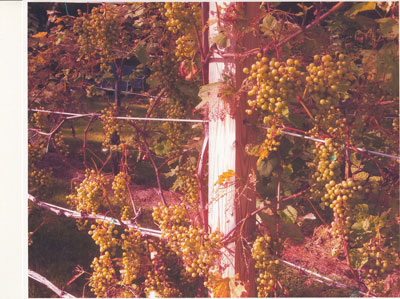

Wow, that’s quite something! Though you seem to have been able to identify the insects on sight, your picture definitely shows the tell-tale “lacy” cutout pattern on the leaves that are the hallmark of the voracious “Japanese Beetle” (Popilia japonica). These little half-inch long bugs tend to be present in the Midwest and eastern United States and like to feast on roses, hops, and, as you well know, grapevines. Like just about all vineyard pests, there really is no way to eliminate them entirely but they can be “managed,” especially in the long-term. First of all, Japanese beetle traps seem to have limited functionality as the pheromone bait, in various studies, was shown to actually attract more beetles then they trapped. Since they are slow-moving and are especially inactive on cold mornings, small infestations can be managed by hand picking them off and discarding them into a bucket of soapy water. Larger areas affected by many of them can be treated with pyrethrin sprays, which are natural, biodegradable insecticides and repellants derived from plants. Insecticidal soap and kaolin sprays have also shown to have good effect as a barrier to feeding.

A really innovative and completely natural way to control Japanese beetles is to implement a longer-term biological control program utilizing one of the insect’s natural enemies, the “milky spore” bacteria. Also known as Paenibacillus popilliae, these bacteria are sold in powder form and are lethal to the grub phase of the beetle’s lifecycle. It’s available at garden supply stores, especially those catering to organic gardening, and can be applied to large areas, so this might be especially suited to your situation. It’s considered harmless to food crops and can be used around pools, in gardens and around pets and kids with no ill effects. The downside is that it can take three to five years to be completely successful as it can only act on the larvae and not on the adult beetles. It won’t be any good against an active infestation, but with time it will definitely reduce the population.

I’m not at all surprised the grapes tasted sour. Without their “photovoltaic cells” (aka leaves) to produce carbohydrates during photosynthesis, it’s not hard to guess why their natural sugar levels were a little bit lower as they approached ripening this year. I hope that you and your daughter have luck managing your Japanese beetle population. There’s no magic bullet but implementing a program now will reap benefits for your vineyard, and her entire yard and garden, in the long run.

Q

I have two wines made from grapes and stored in oak barrels. During aging I have monitored for free SO2 routinely (every 3-4 months) and topped off with the appropriate sulfite necessary based on the pH and the calculations from the sulfite calculator at www.winemakermag.com/sulfitecalculator. Herein lies my question: I would like to blend these wines prior to bottling. If the free SO2 is appropriate for each wine separately, will I need to retest and adjust again after they are blended? Or can I assume that the combined wine will have the correct free SO2 based on the fact each separate wine was adjusted properly?

Greg Ambrose

Pottstown, Pennsylvania

A

You bring up a very good question. For the compound you’re talking about, sulfur dioxide, you’ll probably come pretty close to what you would predict based on knowing the volume and the current free SO2. This is just like alcohol, residual sugar, or titratable acidity and can be predicted based on a simple volume to analysis algebraic equation. The one analysis number that never seems to behave this way is pH. This is due to the “buffering capacity” of pH and how it will change based on so many other components in the wine. Because of this, when it’s blended and encounters so many new components, it may respond in slightly unpredictable ways (say, change from a 3.65 to a 3.62, if you were blending two different wines with the same pH together) and will be impossible to calculate as a true algebraic average.

This is where it does get a little tricky with free SO2 and why I say you’ll likely get pretty close . . . and not exact. Free SO2 is pH-dependent so I would expect to get a little FSO2 shift up or down depending on how much the pH of your blend moved. For this reason, it’s always best to re-check your FSO2 after a major move or blend and adjust accordingly.

Want a quickie “cheat” or can’t send your sample to a lab? In my experience moving and blending wine around over the years, you should be safe (or safer) if you add about 10 ppm SO2 to the wine after you’ve moved it. If you’ve come down a bit you’ll bump it back up, and 10 ppm over “ideal” range isn’t a deal breaker. Ideally we measure volatile acidity (VA) and FSO2 every month so we can bump the FSO2 back up when we top monthly. At the very least, you’ll want to measure FSO2 as you approach bottling.

Q

I just finished harvesting my Merlot and Syrah today and found out I have more Merlot than I can handle at one time. If I stabilize the rest with SO2, can I freeze the must for use later?

Tamara Patrick

Wilder, Idaho

A

If you have the freezer space I say freeze, freeze away! It’s actually somewhat common (for those grape producers who specialize in it like Brehm Vineyards, Vino Superiore, or Wine Grapes Direct) for growers to freeze grapes and ship them to areas of the country where they don’t grow so well naturally. I myself used to send Muscat grapes to a commercial food freezer in Watsonville, California to make Bonny Doon’s famous “Vin de Glaciere” dessert wine in which we pressed semi-frozen grapes to extract concentrated juice.

A difference you might notice when your frozen grapes are thawed for fermentation is that the grapes will be softer and may give up their color and tannin more easily. This is because the grape skin cells, where all the color resides, get pierced by ice crystals. Maceration might be easier and fermentation might in fact be faster because compounds within the grape, including sugar and nutrients, will become available more quickly. This may mean that you will want to especially watch your fermentation temperature and keep things a little cooler if possible. Red ferments tend to get “cranky” when temperatures get above 90 °F (32 °C) because most yeast just won’t tolerate those conditions, especially in the face of increasing ethanol.

One easy hack to try, if you don’t have any kind of jacketed fermentation vessel or cool ambient temperatures, is to toss in frozen “blue ice” packs or frozen water bottles during punch downs. As long as your “blue ice” frozen ice packs or water bottles are completely sealed, they’re a safe, cheap and easy way to cool a heated fermentation down. The larger your must container, the more cooling power you’ll need, however. A couple of frozen 1-gallon (4-L) water jugs should be able to significantly control the temperature of a hot and heavy 30-gallon (114-L) fermenter. Just remember to monitor temperature carefully while cooling because you never want to rapidly chill a fermentation or it will risk sticking. I try to never drop the temperature more than 5 °F (3 °C) in a one-hour period.

Freezing grapes can be an effective way for a home winemaker to take more control of the abundance of the harvest — and to give your cellar and your calendar some much-needed breathing room. Just be aware of the possible changes that the already-burst grape berry skin and pulp cells may bring.

Q

By mistake I added 45 grams of potassium metabisulfite to 16 gallons (60 L) of wine. I have three questions: Is the resulting mixture dangerous? Can it be remedied? And can the grape juice eventually be turned into wine?

Melvyn Atkins

Via email

A

I’m not sure if in the above question you are referring to having over-added to grape juice or to finished wine. Regardless, adding 45 grams of potassium metabisulfite, which is about 58% sulfur dioxide (SO2), to 60 liters of wine will yield quite a bit of SO2 (to put it mildly). I calculate that’ll get you about 430 ppm (mg/L) of SO2, which is well over the normal 70-100 total SO2 that most finished wines will carry while aging. We tend to want finished wines to carry around 25-30 ppm “free” SO2 and since I don’t know your pH it’s hard to say what you might be carrying here, but I’d be willing to bet it’s so high you can smell and taste some overpowering, unpleasant aromas.

It is sometimes possible to remove or reduce sulfur dioxide from wine using hydrogen peroxide (see “Wine Kit First Aid” in the December 2002-January 2003 issue.) but I think your level here is so high that the cure would probably be worse than the disease. Hydrogen peroxide is a strong oxidizer and at the levels you’d have to add the hydrogen peroxide to bind up with the sulfur dioxide (which is the opposite — an antioxidant) would probably ruin the wine’s taste and aroma.

After having added that much potassium metabisulfite to 60 liters of wine, I wouldn’t drink it and the wine is indeed very possibly undrinkable to your tastes. Sorry to be the bearer of bad news.

Q

I have a one-year-old Merlot that has a pH of 3.8 and a titratable acidity (TA) of 54. Can I add tartaric acid to a wine that old?

Rich Thomas

Volant, Pennsylvania

A

You can absolutely adjust acidity in a wine when it is one year old. Though I often say that it’s best to do major adjustments early on in a wine’s life (since the additions will have time to integrate better) it’s always possible to make tweaks further down the road if you think it makes the wine better. Actually, I think a little tartaric bump, maybe around 1 g/L or so, will really benefit the long-term aging and microbial and color stability of your wine. A pH of 3.8 is a little bit high and if you can get it down just a tad you’ll find your free SO2 will stick around longer, your chances of a runaway VA (volatile acidity) will lessen and your Merlot’s color might be preserved longer.

As always, I recommend “bench trials” (small-scale additions to a series of 100 mL lab samples of your wine) so that you can taste and find that sweet spot. Adding a touch of acid might renew the “zing” and really perk up the wine from a taste bud sensory point of view.