Dealing with sediment or lees is among the messier tasks in winemaking. These substances may be thick, occasionally viscous, or gritty, and in certain cases, have an unpleasant odor. Lees are sediments that settle at the bottom of a vessel after it stands undisturbed. As we progress from grapes to the bottle, racking the clear liquid off the lees, each time the overall volume of lees will decrease.

When referring to lees, not all lees are the same. Lees are classified as “gross” or “fine” based on the process stage. “Fine lees,” sometimes just referred to as “lees,” are wine sediments formed during fermentation and aging that can enhance wine quality. If we are in the juice phase, pre-fermentation, then we classify it as “sediment” or “gross lees.” This includes pieces of grape skin, pulp, seeds, dirt, and whatever else comes in on the grapes (often including a few fruit flies and/or bees).

Throughout this article, we’ll dig deeper into the different types of lees, when they can be of benefit and contribute positively to wine aging on them (and in these cases, how to maximize this benefit), and when they can negatively influence your wine if left in contact with it.

Gross Lees

There are many benefits when making white wine to racking the clear juice off the sediment prior to fermentation. Press the juice into a container, allow the juice to settle for 24–48 hours, then rack the clear juice off the sediment and into a fermentation vessel. We have just separated solids, spoilage microbes, and other components that can cause off-odors in the finished wine. This adds a crucial step to the process prior to inoculating our juice and starting fermentation, but it is worth the time and labor for a higher quality wine.

The amount of sediment you are dealing with at this stage has a direct relationship to the production method, and/or if you add any products to help with your press fractions. For my white and rosé wines, I prefer to process the grapes whole cluster — although more labor-intensive at the press, doing so decreases the overall volume of sediment or gross lees because there is less maceration with the grapes. Shoveling whole cluster grapes directly into the press means you will have to fill, run a press cycle, and empty more times because the whole cluster takes up more space in your press. This method may not work with all the small-scale press equipment, so you will need to check the manufacturer’s instructions. The extra labor and time it takes to run whole cluster grapes pays off when it is time to rack the clear juice off your gross lees as it results in a better recovery percentage.

If we take those same clusters and put them through a destemmer/crusher prior to filling the press, we would be able to fit more into the press, but the resulting juice will have more sediment due to the increased maceration. If you are using an enzyme, this will have the same effect because the enzyme is breaking down the cell walls. As a result, there will be a higher percentage of gross lees, decreasing the recovery because of the maceration process.

Either way, after removing the sediment I like to spread it in the vineyard to add nutrients like nitrogen to the soil.

Fine Lees

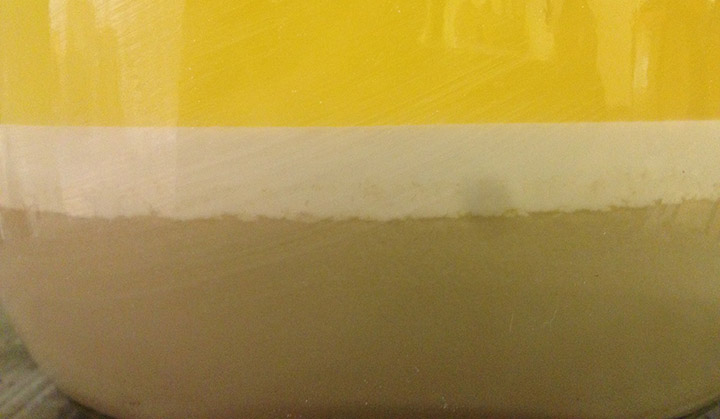

After fermentation is complete, we now refer to the sediment as “lees” or “fine lees.” Using lees as a tool, we are typically referring to white wines and the impact these lees can have on the wine (though some winemakers do age red wines on the lees as a technique to soften tannins and stabilize color). The fine lees are a byproduct of fermentation and are composed of dead yeast cells. All the yeast cells that conducted your fermentation — converting sugar to alcohol and carbon dioxide — fall to the bottom of your vessel starting in the stationary phase and into the death phase of your yeast’s life cycle. Forming a thick, gooey, gritty layer that can be as solid as creamy peanut butter and can sometimes resemble the color of baby poop in a diaper.

When removing lees from your fermentation vessel, dilution works best to help unstick from the sides and bottom of the carboy. On a larger scale, it is best to squeegee into buckets and have a place you can dump outside or in the vineyard. Depending on your plumbing, you may or may not want it to go down your drain. We were on a septic system with a leach field for several years prior to hooking up to the city sewer, so nothing went down the drain. When dealing with several hundred gallons (over 1,000 L) of yeast lees, I started referring to them as “wine mud,” because it would usually end up everywhere just like when you were a kid playing in the mud. Getting the lees out of the tank becomes a bucket brigade, filling, walking out to the vineyard and then starting the process all over until they are all eliminated is no easy task. Lees are a percentage of the total volume. As you increase your batch size, you consequently increase the volume of lees. One of the things I appreciate with small-scale winemaking is that the volume of lees was very manageable. Like realizing how easy it is to clean a press, you do not have to climb in with a full rubber suit for hours, trying to eliminate all the grape skins.

The shape of your tank can have an influence on the recovery of clear liquid vs. solids or lees. For juice settling and fermentation, a tall, narrow cylinder is used to minimize loss associated with solids settling. If your vessel is short and has a large diameter floor, then there is more surface area and it is harder to rack and recover clear liquid. The longer we allow the wine to sit, the more compact the lees will get and the better our recovery. Keep in mind potential issues may arise from extended time on the lees, mainly off-odors, so keep smelling your wine.

It is possible to filter both the gross and fine lees; unfortunately, it is a slow process and labor-intensive, unless you have equipment specific for filtering sediment/lees. We used an old apple press, and by the time we had filtered the juice sediment or gross lees the juice had started a wild fermentation and had elevated levels of volatile acidity. We tried filtering the fine lees also, and that took even more time because it was terribly similar to trying to filter peanut butter. In the end it was best to use tall, skinny tanks and allow it to form compact layers for a better recovery.

Benefits of Aging on the Lees

In white wine production, fine lees are sometimes incorporated as a method that can influence the characteristics of the wine. Everything in winemaking has positives and negatives, we need to know the theoretical vs. practical side to each for maximum benefits. Knowing what they are allows the winemaker to use fine lees as a tool.

The magic of these fine lees is a process known as autolysis, where dead yeast cell membranes rupture and open, releasing their contents into the wine. Lees consist of mannoproteins, amino acids, fatty acids, and tiny amounts of polysaccharides. If we want to gain benefits from the fine lees, then after fermentation is complete we will add sulfur dioxide and seal up the vessel with a solid bung. The wine is no longer producing carbon dioxide, so we need to prevent oxygen from contacting the wine. Sur lie, French for “on the lees,” is the process of keeping white wine in contact with fine lees to gain their benefits. If we are using the sur lie process, then we do not want to leave out another French term, bâtonnage, meaning “lees stirring.” Stirring the lees boosts benefits and helps prevent off-odors. The duration that wine remains sur lie depends on the winemaker, with most sources indicating a range of 8 to 10 months for many wines, and from 1 to 5-plus years for Champagne, depending on the desired style and outcomes of the process. With my barrel-fermented Chardonnay, I would age the wine sur lie for 3–6 months.

There are many benefits to aging a white wine sur lie: Softer mouthfeel, adding weight and texture to the wine, the additional flavors and aromas, deacidification, or a decrease in the sharpness of the acid. Lees can be a winemaker’s friend also in the prevention of unwanted oxidation, as the mannoproteins will absorb residual oxygen. Extended time on the lees adds structure to wine while maintaining its freshness. Lees can also function as a clarifier, aiding in protein stability and making it easier for lactic acid bacteria to perform a malolactic conversion. Each time we perform bâtonnage and bring up the lees from the bottom of the vessel we are allowing more of these positive traits to happen: More flavor and aroma, clarification, and protein stabilization of the wine. The wine is richer, has a creamy texture adding to the complexity of the wine.

This process is typically used with Chardonnay and other varieties of white grapes in cases where the winemaker is looking to add more body, texture, and flavor components that complement the grape variety. Think of Champagne made in the traditional method, where it spends years on the lees in the bottle. Those lees are adding to the mouthfeel, changing the flavor profile that emphasizes brioche, biscuit, yeasty, and nuttiness characters. With German Rieslings, wines are aged sur lie for months to help eliminate the sharpness of the acidity. This process can be beneficial to other high-acid grape varieties as well, like Aromella, Vidal Blanc, and Vignoles.

Sur lie aging is less common for red wines, though some winemakers do keep their red wines in contact with lees as a way to improve color stability, soften tannins, and add complexity to the wines.

Risks of Aging on the Lees

We touched on the many benefits of aging wine on the fine lees; we now need to look at what could go wrong. The lees consist of dead yeast cells, and during autolysis, their cell membranes break down, releasing the contents from inside the cell. While we have discussed the benefits of mannoproteins, amino acids, and polysaccharides, I have not yet addressed the possible negative components that may be released. In my previous article on yeast nutrition “Keys to Successful Fermentations,” I explained the amino acid synthesis that is going on within the yeast cell during its life cycle. Yeast cells absorb sulfate and sulfites, subsequently converting them to hydrogen sulfide. In the presence of nitrogen, this compound facilitates the formation of the amino acids cysteine and methionine. Disruption of this pathway by low nitrogen, pantothenic acid deficiency, or yeast stress leads to toxic hydrogen sulfide production during fermentation, resulting in a rotten egg odor. The thing to remember is that hydrogen sulfide is naturally occurring within the yeast cell. Even if the odor disappears during fermentation, hydrogen sulfide can still be released during autolysis. I make a note during my fermentation if I stress the yeast and/or smell hydrogen sulfide, lending itself to be cautious of aging the wine on the fine lees.

As the yeast cells begin to fall to the bottom of the vessel, another issue that can arise with sur lie is they can become compact, beyond the reach of oxygen, and become reductive. Issues can arise through the balance between the level of off-smelling sulfur-based compounds and the amount of available oxygen. When present, oxygen beneficially counteracts these compounds. However, when a wine contains a higher amount of these negative sulfur-based compounds and not enough available oxygen to mitigate all of them, then the wine is referred to as being reduced. Sulfur substances like sulfur dioxide can also be reduced to hydrogen sulfide. We refer to all these chemicals collectively as Volatile Sulfur Compounds (VSCs). These encompass hydrogen sulfide (rotten egg/sewage), dimethyl or diethyl sulfides (cooked corn/rubbery/truffle), mercaptans (rubber/burnt match/rotten cabbage) and dimethyl or diethyl disulfide (rubbery/vegetal/cabbage/onion).

Bâtonnage, or stirring of the lees, can be helpful in bringing up the lower thick gooey layers of fine lees and introducing them into the main body of wine and encountering a bit of oxygen. When you are stirring a barrel or carboy, try and scrape the bottom to get the thick, gooey lees. Doing this on a larger scale becomes a bit harder. Some use a Guth mixer or pump wine from the top of the tank going in through the bottom valve to fire hose them loose.

Special note: If you are making a wine with residual sugar and stopping the fermentation prior to dryness, then you would not want to keep your wine in contact with the lees. While most are dead, it will take a while for all of them to die and the possibility of fermentation starting back up is a risk. The best way to stop your fermentation prior to dryness is to remove yeast lees quickly; we want to remove the yeast and lower the population as much as possible to arrest the fermentation.

Conclusion

I have used sur lie aging with remarkable success; it is a great tool. I also had a tank of Riesling that had completed fermentation, added sulfur dioxide, but did not have time to rack off the lees. Due to the demands of the harvest, this task was deprioritized on my to-do list. I kept tasting it and started noticing a petrol component developing, which was exciting. That excitement turned to concern as the petrol morphed to more of a rubber component in a couple of days. Racking this Riesling off the fine lees became an urgent priority. It developed a hydrogen sulfide problem that required copper sulfate trials for resolution.

Like all tools in winemaking, we need to weigh the risk against the results. Ask yourself what you want to accomplish and how healthy your fermentation was. Understanding the nuances of lees management and the science behind sur lie aging allows winemakers to make intentional decisions tailored to the style and quality they seek. As with all aspects of winemaking, observation and adaptability are key. Regular tasting, thoughtful record-keeping, and a willingness to adjust techniques as needed ensure that the lees become an ally rather than a source of fault. The judicious use of lees can elevate a wine from ordinary to extraordinary, adding complexity, harmony, and a signature character that reflects both the grape and the hand of the maker.