Monitoring Malolactic, Adding Skins, Timing Purchases, Airlocks

Q We’ve got about 8 gallons (30 L) of Sangiovese that just finished fermentation. given the higher acid content (0.8 after fermentation), I’m going to put it through malolactic fermentation (MLF). i’ve seen many resources on how to test for progress of mlf; However, none of the resources answer the simple question: Can I visually see MLF in action like I do with alcoholic fermentation? Will there be any fizzing or bubbles? Is chromatography the only way to make sure that the bacteria have survived and are doing their job? Just trying to figure out how best to understand when MLF takes off and starts getting to completion.

Jim and Janet Nelson

Murphys, California

A MLF is a bit confusing for some because it’s called a “fermentation” but it’s certainly not as active, visible, smellable, and in your face as your primary sugar-to-alcohol fermentation. MLF happens when naturally present (or artificially introduced) bacteria turn the malic acid in wine into lactic acid, producing a small amount of carbon dioxide gas and some aroma and mouthfeel components. I agree, you should put your Sangiovese through MLF; it’ll deacidify the wine a bit, will round out flavors, and will prevent MLF happening later in the bottle.

MLF sometimes happens on its own, concurrently with the primary fermentation, so it may go to completion without you noticing anything at all. After primary is over, most commercial winemakers will run an enzymatic assay that measures the level of malic acid in the wine; this way they can tell if MLF is complete or not. Unfortunately, most home winemakers don’t have access to the expensive equipment and reagents to do this kind of analysis, but luckily you can still send a sample of wine to a commercial wine lab or do the old fashioned (and cheaper) paper chromatography assay. Kits can be purchased from scientific supply houses and from most winemaking stores and websites for under $50.

If you inoculate for MLF (I like the freeze-dried variety available from Gusmer Enterprises), depending on how quickly the fermentation happens, you may or may not notice anything. Sometimes, if you put your ear to the bunghole, you’ll be able to hear little “pinpricking” bubbles of CO2 being evolved, though not always. In cool climates, especially, and in high-acid wines where the bacteria have a hard time surviving, you may not be able to hear the fermentation happening at all. Slow MLF can take months to completely turn all the malic acid in the wine into lactic acid; watch out because the wine will not be protected by a lot of carbon dioxide gas at this time so is very susceptible to infection by spoilage bacteria and increased volatile acidity (VA) production.

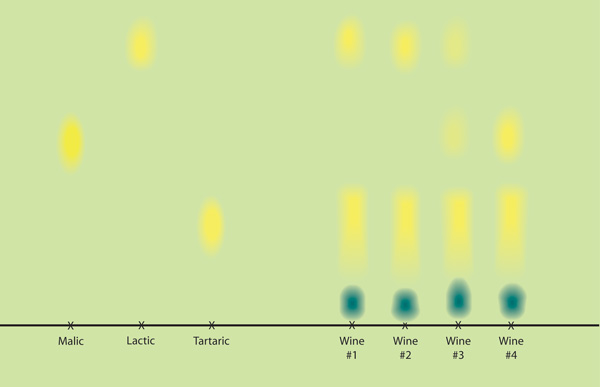

If you don’t hear any pinpricks and you suspect your MLF is dragging on for over a month or two, it’s always wise to use a chromatography kit to check for and/or monitor the completion of the fermentation. Unfortunately, chromatography isn’t a great quantitative assay — it is only an “indicator” assay and shows a malic and lactic acid “signature” that appears as a colored blob on the chromatography paper. Experienced chromatographers can see differences in the sizes of the respective blobs (as MLF finishes, the malic acid blob disappears and the lactic blob gets bigger) and track the relative completeness of MLF, but it does take some practice. This is why commercial winemakers and serious home winemakers are moving away from chromatography and send samples to wine labs for an empirical numerical result. In addition, the solvent (butanol, formic acid, and bromocresol green indicator) needed for the chromatography assay is really toxic so I prefer to spend the money on enzymatic assays in order to keep it out of my cellar.

Either way you choose to monitor your fermentation, in red wines you usually want MLF to finish. For whites, whether you add SO2 early and keep some malic acid for crispness is up to you and your stylistic desires. I never recommend MLF for rosés as I find the bright pink color suffers and the wine can turn orange and even brown if left to go 100% ML complete. Remember, if you have residual malic acid in your wine you will have to either bottle with high (over 35 ppm) levels of free SO2 or sterile filter before bottling. Malolactic bacteria are ubiquitous in the environment (you’re probably breathing some in right now), so if you’ve got malic acid in your wine, it’s almost certain the ML bacteria will chow on your wine and you’ll get CO2 bubbles and off-aromas in the bottle.

Q How many grape skins would be too many to add to a Syrah must? This fall I will be able to buy half of a 1,500-lb. (680-kg) crop of quality, dry-farmed Syrah. The owners of the vineyard will use the other half to make a rosé. I will have access to the skins from the rosé to make my red wine more intense with darker color. My gut tells me that I would be asking for trouble to add all of the skins from the 750 lbs. (340 kg) used for rosé. Can you recommend an upper limit for this experiment? Any other caveats?

Greg Bequette

Livermore, California

A There’s an ancient tradition of making wine using skins “donated” from other fermentations and projects. The one you list above is one such scenario. The most well-known incidence of this practice includes the “Ripasso” wines (which means to “re-pass”) from Italy where the dried and pressed skins of one dark red grape are used to enhance the fermentation of another, lighter wine.

Your situation seems like it’s an interesting idea. I think that the amount you choose to add should be determined by looking at the quality of the Syrah grapes in question. Indeed, my first question would be: Will the vineyard owners be picking their half for rosé a lot sooner than you might want to be making your red wine? Typically, rosé grapes are picked at a much lower Brix and higher acid than for making red wine; say about 23 °Brix and 3.4 pH. Those numbers aren’t great for red winemaking. So are you planning on coming to some compromise with them where you’ll all be happy with your initial Brix and acid balances? Otherwise, if they pick two weeks earlier than you there’s no way for them to keep those skins “fresh” and usable while you wait for your half of the vineyard to get ripe.

Let’s pretend, however, that you all decide to pick when the grapes get into red winemaking territory, say around 24.5 °Brix and 3.55 pH. I still wouldn’t be inclined to use all of the Syrah skins. I would think that adding much more than 30% would start to make it difficult for you to “work” your red fermentation, i.e., it would be really difficult to punch down/pump over (depending on your cellar setup). I would think an inclusion of about 30% to be ideal. That way you’ll benefit from the extra “oomph” provided but in case the grapes are really tannic you won’t go overboard. Let your taste buds be your guide. Do the skins taste pleasant, have great color, and are they nice and ripe? Or are they bitter, tannic, and green? The more pleasant they are the more you can increase the dose, up to a point where your must becomes too difficult to work with. It also risks adding too much tannin to your wine. If you taste your wine during fermentation and believe it is becoming too tannic, you can press the must a bit early and finish alcoholic fermentation in the next vessel minus the skins and stems so even more tannins are not absorbed.

Q I always restock my cellar with chemicals, yeast, and malolactic (ML) bacteria in August for the upcoming season. As soon as I receive the yeast and ML I store it in the refrigerator or freezer. So far I have not had a problem that I am aware of, but should I consider ordering yeast and ML during the winter to avoid the summer heat during shipping?

Martin Guerrero

Laredo, Texas

A That’s a great question and one, like so much in winemaking, that can be answered by a bit of a compromise. You’re on the right track by ordering your supplies right before harvest — live or even freeze dried “bugs” (microorganisms) like bacteria and yeast, as well as chemicals like malic acid and yeast nutrients, all have a shelf life, some much shorter than others. It’s always a good idea to use the freshest, most potent supplies that you possibly can to ensure the highest quality winemaking once the grapes start rolling in. That being said, if you order too late in the season, sometimes suppliers will be out of materials that you particularly wanted and, horrors, you will be subject to the dreaded back order! In addition to that, as you bring up, your delicate liquid yeast culture could get cooked en route by a careless delivery service.

So what is a conscientious winemaker to do? I suggest talking to your suppliers to find out the shelf life of all of the winemaking adjuncts you use and see how early you can safely order them. Things like yeast and ML cultures should be ordered right before harvest — I get my yeast delivered no more than a month before I expect the first grapes to be rolling in. Things that have a longer shelf life like tartaric acid, soda ash, or oak beans can be ordered up to six months beforehand, but three months is usually enough time to give your suppliers notice for your order while still leaving you enough of a window in case something needs to be back ordered. This also lets you do your shipping in the late spring, perhaps before temperatures start to climb towards the summer highs in your area.

I wouldn’t be overly concerned about shipping conditions for most of the things you might order. Items that tend to be most affected by high temperature include yeast, bacteria, and enzymes, and these can be shipped in Styrofoam containers with cold packs if necessary. My freeze-dried bacteria cultures arrive in said manner and, as long as I pop them in the freezer the same day they’re received, they seem to get along just fine. I’ve never had any problems with “static” additives like acids, cleaning agents, bentonite, tannins, or oak products being exposed to extreme temperatures, hot or cold. All of these items, and those like them, are quite hardy.

The bottom line is that you don’t want to order so early that you run up against expiration dates but you do want to order with enough of a window before harvest so you can ensure you’ll have everything delivered before the grapes start flying. Luckily, wine industry suppliers seem to understand this timeline to meet the needs of winemakers.

Q I’ve been making red wine from musts for a couple of decades now and I’ve always used a fermentation airlock around the third day of vigorous fermentation. Can you let me know the pros and cons of using it early on as I do compared to using it towards the end of the fermentation process? I’ve got friends who don’t use one during the whole primary and only at the end where the wine really slows down and no longer produces CO2 to protect it from oxidation.

Robert St-Jean

Gatineau, Quebec

A Kaboom! Nobody likes an exploding carboy! “Fermentation happens,” as one of my professors at UC-Davis always used to say. Sounds like the perfect home winemaking meme to me (or t-shirt). As wine can produce quite a lot of carbon dioxide (CO2) gas, if that gas is trapped it can literally blow the top off your carboy, bucket, or barrel. Hence, we all love our fermentation locks. But when to use them? In general, anytime there’s too much CO2 being produced such that you can’t put a “hard top” on your container . . . but read on for some elucidation and detail.

When you’ve got a raging fermentation, like during days 3–6 or so when it’s really going, you can get away with covering the mouth of your vessel, whether a barrel, carboy, or a food-grade pail, with something like cheesecloth. A fine-weave cloth will do a great job of keeping the fruit flies away while the healthy amounts of CO2 coming off of your fermentation will protect against spoilage organisms.

However, when the fermentation is “ticking down” to its final degrees of sugar or malic acid and is no longer producing copious amounts of CO2 gas, it’s probably time to switch from the fabric stretched over the opening of your fermenter to a fermentation lock. Depending on how fast your fermentation is, that will likely be around day 8–10 of fermentation.

The water trapped in the “u-bend” of the fermentation lock lets the last of the gases escape yet doesn’t allow as much “dirty” air from the outside back in. Spoilage organisms like yeast and bacteria are circulating in the air all around us so while you still are off-gassing to some extent and aren’t ready to “hard-cap” your vessel, a fermentation lock is the way to go.

So there is no doubt that the most important time to use a fermentation lock is when your fermentation is still producing just a bit of CO2 and hasn’t quite stopped yet, as described. However, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t use a fermentation lock on a carboy before it starts taking off. It’ll do no harm and may do some good in stopping more microbes from potentially entering your vessel than if you just had it covered by fabric during a time when it’s still juice and hasn’t started producing CO2. Since it’s difficult to predict exactly when the fermentation process will begin, I find it’s better to be safe than sorry. My readers know that I’m all about excluding those spoilage microbes at all costs.

If the fermentation really takes off and you find your fermentation lock continually blowing itself off the top of your carboy due to high levels of gas being produced, it’s fine to switch to a fabric covering for a few days before replacing the fermentation lock when things calm down a bit. Then, when all fermentation is complete, it’s OK to “hard bung” your carboy, barrel, etc.

No matter the stage of your fermentation, I’m always a huge fan of using some kind of covering. Fruit flies and other household nuisances (even overly inquisitive pets) need to be excluded from sugary containers at all times.