Aging your new wine in an oak barrel can do wonders for it — or ruin it.

Aging your new wine in an oak barrel can do wonders for it — or ruin it.

If you want a stark example of what it means to be ambivalent, get a professional winemaker talking on the subject of oak. He or she will sing the praises of imported French barrels made from oak harvested in hundred-year-old groves, which, when air-dried and toasted, impart an exquisite depth to a rich Cabernet or Syrah. Then the same vintner will turn around and complain bitterly about the barrels’ breathtaking cost, their tendency to leak and lose flavor in a few seasons, and their propensities to waste wine through evaporation and to harbor spoilage microbes, so that they require perpetual refilling and fanatical care.

All that said, oak barrels do several remarkable things, apart from looking classy in a cellar. Wines aged for months in oak barrels not only show gentle vanilla aromas and flavors, but may also be noticeably softer, darker, and more concentrated than the same wines held in glass or stainless steel — they’re better, in other words. That’s why most top wineries age their red wines in oak.

Even if you turn out a modest amount of wine on a home winemaking scale, you can follow a commercial winemaker’s lead. Barrels permit your wine to oxidize slowly, a process that helps to stabilize the color and soften the taste. The wine also absorbs tannins from the wood, as well as numerous flavor compounds including lactones (oak, coconut), furfurals (caramel, butterscotch), eugenols (clove, spice), guaiacols (smoke, char), and vanillin (vanilla).

The barrels sold most widely in home winemaking shops are made in the United States from oak grown in the American Midwest and Southeast. But barrels made of French, Canadian, and Eastern European oak are also sold. Different makers use different cooperage methods. French oak is typically hand split before being shaped into barrel staves, while American oak may be sawn. On top of this, most barrels’ inner surface is toasted by exposure to an open flame. Adjustments in the length of the exposure to fire (roughly 10 to 30 minutes) give the barrels varying degrees of toast: light, medium, medium-plus, and heavy.

One California winemaker says he can discern distinct flavor characteristics in more than 60 different products from more than 20 different barrel makers. Here’s how he describes a Seguin Moreau barrel made with American oak staves and French oak heads: “All the richness of American oak with subtle nuances of finesse from the French heads. The use of heavy toast allows this barrel to produce great, smoky, dark-chocolate aromas and flavors, with subtle cinnamon and brown sugar in the background.” Some winemakers pursue similar complexity by aging a single batch of wine in both American and French oak.

The bind for home vintners is that sweet deals are hard to find. New oak barrels — even small ones — can cost between $300 and $1,000 apiece. And used barrels are a devil’s bargain. You may find one at a good price, but it’s hard to know whether it’s been banished for a reason: Perhaps it sat empty too long and smells of vinegar, or it has leaked ever since it was new, or it’s old and mostly flavorless, or, quite possibly, it’s contaminated with invisible microbes that will taint any wine aged in it with a funky, earthy aroma.

Happily, some benefits of barrel aging can be achieved in other ways. For oak flavor, products available at home winemaking suppliers have turned things upside down. Instead of putting the wine in wood, as is conventional, it’s possible to put wood in the wine, in the form of specially processed oak chips, cubes, or staves (see sidebar on page 41). Vintners at boutique wineries sometimes like to scoff at these products as ersatz and downscale — the enological equivalent of liquid smoke — but for home winemakers, they’re a legitimate way to add a bit of complexity. (And many commercial winemakers have been known to use oak alternatives as well.)

In other words, it pays to think twice before shelling out for whichever barrel is on hand in your local winemaking shop. And, of course, there’s no point in filling a beautiful oak barrel with iffy wine. But if you’ve invested in great grapes and want to lift your wine to the next level of quality and complexity, barrel aging may be for you. To the important decisions about using barrels, here are answers to some of the most common questions about oak.

What’s the right type of barrel?

As with many aspects of winemaking, you get to decide the answer to this question. The age-worthy red wines of France have traditionally been aged in new or largely new barrels made of well-cured, tight-grained oak harvested in forests of the French regions of Allier, Limousin, Nevers, Tronçais, and Vosges. Italian winemakers have tended to look for cooperage in Eastern Europe — Hungary, Romania, and Slovania. American barrels — made from oak grown in Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and elsewhere — have for decades been the aging vessels of choice for Spanish red wines such as Riojas but are now used everywhere.

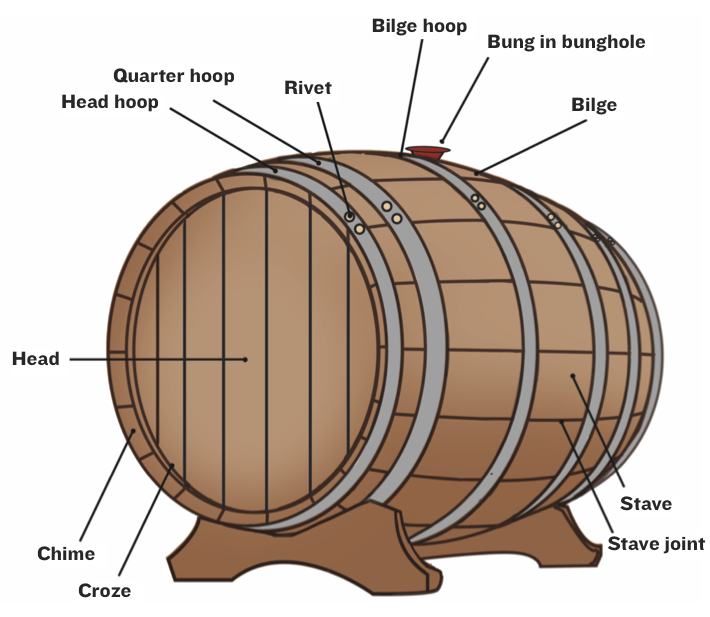

The European-made barrels — you’ll see Burgundy and Bordeaux styles — show up less often in US home winemaking shops than American ones do. Bordeaux barrels are sleek and plain, with six riveted metal hoops binding the staves and heads together. Burgundy barrels are by comparison short and stout, often with rustic hoops of split willow next to the requisite metal hoops. Burgundy versions typically hold a little more wine (228 vs. 225 liters). And American barrels? They look much like the Bordeaux ones, though occasionally a little more rough-hewn.

The difference among oak barrels that matters most is the flavor. American oak (Quercus alba) has wider grain than European oak (Quercus petraea and Quercus robur) and tends to impart a stronger note of vanilla, spice, and caramel, with lighter tannins. European oak, with its tight grain, contributes relatively delicate vanilla flavors but more robust tannins. Of course, the tastes the various oaks contribute can differ dramatically among barrels with light, medium, or heavy (dark) toastings. Medium and medium-plus are popular for barrel-worthy reds and whites; heavy toast, with its deep chocolate flavor, is reserved for rich, tannic red wines.

How can I tell if a barrel is a good one?

To a large extent you have to trust your supplier. But if you do get a chance to inspect the barrel, pull out the bung and poke your nose inside. Because its inner surface has been exposed to an open flame, the barrel should smell faintly smoky, and a finger swiped around the bunghole may come out with some chocolate-colored crumbs — normal signs. But if the barrel is a used one, sniff cautiously because it may have been dosed with sulfur dioxide gas. A pungent sulfur dioxide scent (like burned matches) is evidence of a tight barrel, likely well cared for. Vinegar or funky mushroom smells are signs of microbial contamination.

Peek inside the barrel with a small flashlight if you can. The wood should look light to moderately dark brown, but not charred or blackened or blistered. Also check for cracks in the staves, especially around the bunghole. These are sites of potential leakage, evaporation, oxidation, and microbe intrusion. Because new barrels are shipped dry, you may see slim gaps at joints between the staves or on the heads. Minor openings aren’t necessarily a problem if the barrel is a well-made one. The oak swells when the barrel is filled, sealing the gaps (read on for more on this).

Don’t new barrels need special care?

New barrels usually leak when first filled, a worry to first-time users. Most wineries simply swell theirs with water, but the fine points vary. Some winemakers add several gallons of warm or hot water, drive in the bung, then roll the barrel to wet the entire inside. Next, they tip the barrel onto one end for half a day, inverting it later to soak the opposite end. They may repeat those steps before draining and filling the barrel with wine. Others fill a barrel with cold water right up to the bung and let it stand for a day or two. (But not longer; a barrel with plain water in it shouldn’t sit for more than 48 hours or microbes can multiply and infect the barrel.) Eventually, all the leaks stop — or they should. If your barrel remains leaky, take it back to the shop or contact the manufacturer. Never put your wine into a barrel that won’t swell tight.

The only actual cleaning a new barrel needs is that first soaking. Caustic treatment, suggested in some outdated barrel-care texts, will simply deplete the oak’s flavor. However, it is an option for used barrels — as a way to remove tartrate deposits and to purge faint off aromas.

Which size is best?

If you don’t make enough wine each year to fill a standard wine barrel — about 60 gallons (225 L) — it’s fine to buy a half-size barrel or any down to about 15 gallons (about 57 L). Small barrels are a huge convenience for home winemakers, although they do require special diligence. The basic rule: As the barrel’s size goes down, the amount of oak that each gallon or liter is exposed to goes up. So the smaller and newer the barrel, the more often you should sample the wine to see how oaky it tastes. Once a week is not too often. You want the aroma and flavor to come through as faint hints, not as conspicuous oakiness. A simple insurance policy against overoaked wine is to hold out a portion of the vintage so you can blend the lots later. That is, it’s smart to buy a barrel somewhat smaller than the batch of wine you plan to make.

How long will a barrel last?

A new oak barrel can serve for a decade or even longer. Wine aged in a barrel used for four or more vintages won’t pick up as much oak flavor, but it will still gently oxidize. What’s more, a well-used or “neutral” barrel can be reconditioned at least once by “shaving,” that is, scraping or sanding the inner surface and then retoasting the oak. Some suppliers sell reconditioned barrels — which are a legitimate way to save money — and when their flavor finally fades, you can make up the difference by adding oak cubes. The only downside: Shaved barrels can lose more wine to evaporation through their now-thinner staves (evaporation is discussed later in this story).

What can go wrong?

With a new barrel, scrupulously maintained in a decent home winery, not much can go wrong. Vintners have put faith in wine barrels for centuries and haven’t given up on them yet. But oak, no matter how thoughtfully handled, is a perishable product full of minute pores and microscopic crevices. And any barrel (depending on its size) has several dozen pieces of wood that have to fit together tightly. Problems can crop up.

The oak’s porosity means that both water and alcohol escape through the staves — up to 5 percent a year in a standard barrel and 10 percent or more in a smaller one — leaving a headspace, or ullage, below the bung. Ullage is inevitable, but to fend off oxidative browning and the formation of off flavors from acetaldehyde (oxidized alcohol), it’s wise to keep a regular schedule for replacing the wine lost to evaporation (the “angels’ share,” some call it). Likewise, Acetobacter, the ubiquitous bacteria that break down alcohol and generate vinegary acetic acid, can flourish in the headspace in the barrel created when air seeps past the bung or through the staves. Always top up your barrels.

Even without headspace, barrels can become havens for microbes. If a barrel sits in an exceptionally humid place, mold can grow on it, eventually reaching through the oak to the wine, triggering off flavors. If the rogue yeast Brettanomyces gets a foothold in a new wine, it can infect the barrel so that every wine aged in it later will pick up a funky, barnyard aroma. (Brettanomyces can exploit the smidgens of residual sugar in wine deemed dry.) And the bacteria Pediococcus and Lactobacillus — bugs that spoil the texture and flavor of wines — can also settle in a barrel’s pores, lying dormant until a wine with high pH, residual sugar or malic acid, or a low sulfite level fills in around them.

It all sounds dismal, but there are preventive steps and treatments. Most important is to keep your barrel full of healthy, stable, sulfited wine. The smaller the barrel and the drier the cellar, the more often you’ll need to top up. Don’t let that duty slide, stay on top of sulfite additions, and always use a well-fitted silicone bung.

For a barrel with mild off aromas, a standard treatment is about 5 grams of sodium percarbonate (available at home winemaking shops) per gallon of barrel volume (1.25 grams per liter). Dissolve the powder in warm water, add it to the barrel, and then fill it with water and allow it to stand overnight. Empty the barrel and rinse it several times with hot water before refilling it with a fresh sulfur-citric solution (read on). Drain the barrel after a day and rinse it again with water, then give it a good sniffing before filling it with wine.

What’s the right way to store an emptied barrel?

Few home vintners turn out enough wine each year to keep a barrel perpetually full — although that’s the best safeguard. Some commercial wineries flood their empty barrels with sulfur dioxide from a compressed gas cylinder, an expensive and risky method. Small-scale winemakers have other barrel-care options.

Sulfur wicks, sold in home winemaking shops, are paper strips impregnated with yellow elemental sulfur. Lighted with a match and hung inside a well-drained barrel, the wick gives off sulfur dioxide gas that keeps yeast and bacteria at bay. It’s wise to also buy a sulfur bung, which has a wire hook for the wick and a cup to catch any drips, which might later taint your wine with a rotten egg smell. When the wick burns down —

a one- to two-inch piece suffices — replace the special bung with the regular one and jam it down hard to keep the gas in. (First be sure to cover the bung with plastic wrap from the kitchen to keep the sulfur dioxide from degrading it.) The hitch in this method is that new wick should be burned in the barrel about once a month. Quick sniffs at the bunghole will tell you when the gas is dwindling. Fail to replenish the sulfur dioxide and there’s a good chance your barrel could go sour — set yourself a reminder!

An even simpler way to protect your investment while waiting for the next vintage is to fill an emptied and rinsed barrel with a sulfur-citric solution of 1.5 grams of potassium metabisulfite and 0.5 gram of citric acid for each gallon that the barrel holds. Granted, your barrel will lose some oak flavor to the storage solution, but you get a payoff in convenience and confidence. Remember, like anything stored in the barrel (wine, sulfur dioxide) you don’t want headspace. Top up frequently and replace the sulfite solution every few months.

Can I skip oak altogether?

Of course. Many superb wines, especially crisp, light-bodied whites such as Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Gris, and Riesling, traditionally are bottled with no oak aging at all. That’s because the wood’s flavor can overwhelm the fruity taste of the grapes. What’s less obvious, because barrels have become an icon of quality winemaking, is that red wines can also do without it. The best wine my wife and I ever made was a Napa Valley Cabernet that fell clear in the carboys while we were between barrels. We bottled it anyway, and no one who has ever tasted it — including some ardent oenophiles — has missed the added flavor. What they’ve often said is “This is a really excellent Cab. Where in Napa did you say the grapes are from?”

For more about making oaking decisions in winemaking, check out Chik Brenneman’s article “Wines Two Ways” in the August-September 2013 issue of WineMaker.

Editor’s Note: Warrick adapted this article from his book The Way to Make Wine: How to Craft Superb Table Wines at Home, 2d ed. (University of California Press, 2015), which is available now at major booksellers.