Winter Chills

Saving the vineyard from cold damage

I’ve got good news for my fellow grape growers out there in the world: Grapevines have evolved to make it through some nasty winters. The European wine grape, Vitis vinifera, developed over millions of years (in the forests of the Transcaucasia region that borders Europe with Asia) to save leftover nutrients after harvest, drop their leaves and create woody canes that can safely overwinter down to below zero degrees Fahrenheit (-18 °C). Hybrids and American vines such as Frontenac or Concord can even take more chilly punishment.

This article is not about frost control during the growing season. This one is for our friends in the northern continental climates — like Montana through Maine in the U.S. and into the Great White North (Canada). If you live in an area, such as most of California, that never freezes lower than 0 °F (-18 °C), you get this issue’s column off, and I direct you to skip this article and enjoy a bottle of Santa Maria Pinot Noir. The 2017s are drinking great right now.

But how cold is too cold, and what can we do if we live in those areas that can cause winter damage to dormant grapevines? Let’s find out!

Brock University in Ontario offers an excellent list of what winter cold can do to a vine and things to watch for after a dangerous cold event. Most of these symptoms will show in the following year, but keep reading for a method to determine damage before pruning.

- Loss of fruiting buds

- Uneven or poor vegetative growth

- Inability to achieve vine balance

- Disease incidence (crown gall)

- Loss of vine growth uniformity in a block or vineyard

- Loss of consistency of production

- Loss of vines

- Additional input costs for renewing and retraining vines

- Reductions in yield, quality, and income

So, as we can see, one hard, cold freeze can ruin years, even decades, of work keeping a vine and vineyard healthy and producing. The best protection starts with a solid education about vines; their physiology; what areas are in danger; and what practices we can complete to assess, protect, and reinvigorate a vineyard after a winter kill event.

Where are the Areas in the Most Danger in North America?

Check out the newly updated USDA Plant Hardiness map found at www.planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/ (or Canada’s at www.planthardiness.gc.ca/).

If you live in zones 1–6, this article is for you!

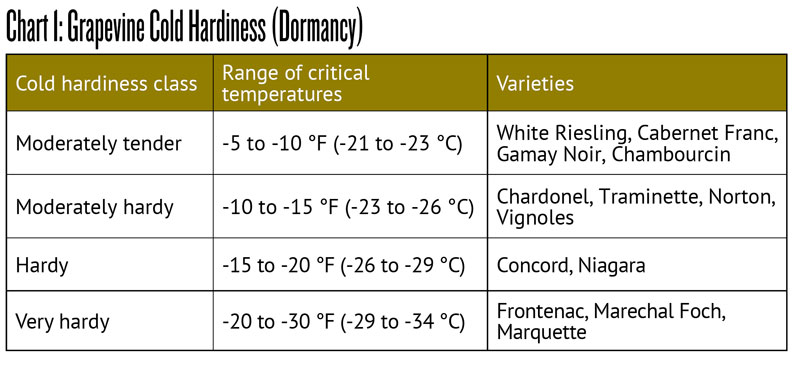

What grapes to grow in a region with very cold winters? University of Maryland Extension gives us Chart 1.

Mitigation methods

- Plant hybrids like Frontenac, Marechal Foch, or native North American vines like Concord. These vines have far greater winter kill resistance than their fleshy and easily killed European cousins.

- “Hill Up!” Creating an under-vine hill of dirt that covers the graft union can do wonders for helping any vine get through a winter kill event.

- In the coldest winters and regions, some vineyards severely prune low-growing vines and “hill up” and cover the entire vine.

- Snow drifts have a similar effect, and if snow is covering the vine, it will likely be insulated enough to get through all but the worst winter kill events.

If you experience weather colder than the temperature ranges in Chart 1, initiate the following protocol:

- Wait until after the harshest winter weather has passed (late winter).

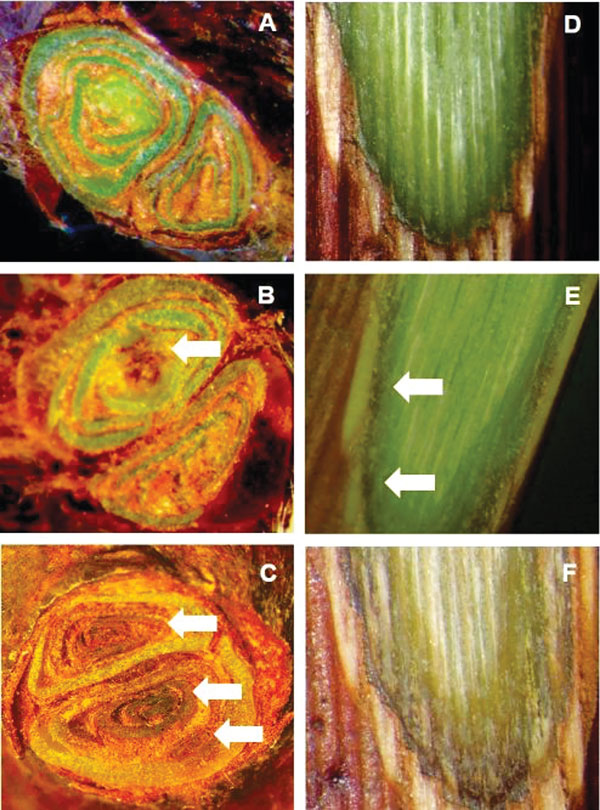

- Use a razor blade to cut into buds and canes to assess damage. Cut open a dormant bud or a dormant cane with a razor blade (careful!), and hope you see results like A and D found in Figure 1 below. Read the descriptions for the other letters to see how to determine levels of damage from chill events. Again, this is only meant for dormant canes and buds — between full dormancy and bud swell.

- Wait to prune as long as you can — look up double pruning and recognizing bud swell, which can both help prune late successfully.

Figure 1: Cold injury to Grape Buds and Canes

A) Healthy compound bud; B) Discolored tissues indicating injury to primary bud; C) Compound bud with cold injury to primary, secondary, and tertiary buds; D) Healthy cane tissues; E) Moderate cold injury to cane indicated by discolored cambium tissues; F) More advanced symptoms of cold injury to the cane. Photos and insights by Paolo Sabbatini, Michigan State University

Viticulturalists also need to consider criteria/warning signs that a winter kill event happened or if it was just damage. Here are signs to look for:

- Blind positions on the vine because of buds that do not grow come springtime. You notice that many of the buds on the wood retained at pruning do not push, break, or grow. This is an indication of cold weather bud death.

- Lower yield or very odd growth patterns the year after cold snap where there is usually consistent vigor. Inconsistent growth from position-to-position and vine-to-vine could be an indication of vine cold damage, especially in vineyards that are usually consistent in their growth from vine-to-vine.

- Loss of fruitfulness in a normally fruitful vineyard the year after cold snap. As seen in Figure 1, fruit buds can be damaged or destroyed even before budbreak.

Now we have some data points on location, temperature, susceptible varietals, and how to recognize cold damage in grapevines. Next, we will discuss strategies to protect your vineyard in the coldest months, and to determine how much protection is enough to have good fruit and growth next year.

Prevention Is Key

If you have a hard freeze and believe the vines may have been impacted, cut into ten buds from throughout the vineyard and ten canes, also throughout the vineyard. If you cut into areas that will be pruned, you will lose no growth or fruit.

If there is damage, you may want to increase to 20–50 buds and canes to cut and evaluate. Then, at pruning, we will leave extra buds on the vine to compensate for those killed in winter.

Check out Chart 2 for some useful tips with this (thanks again to our friends at Michigan State University).

More on bud mortality: So if you notice one bud out of ten impacted by winter kill — prune as normal. If two to five out of ten show winter kill, increase the number of buds retained per vine by 25%. (If you leave 20 buds per vine, go to more like 25. If six out of ten of the razor cut buds you checked are damaged, double the buds retained normally at harvest. Seven or more out of ten, don’t prune the vine and see what lives the next year and re-work the vines back into health and a working pruning style in the next few years. In the worst situations, only the basal sucker shoots (low on the vine) might survive, and you may have to use a sucker to develop a new trunk on a severely impacted winter-killed vine.

Texas A&M published Figure 2, which is a vine growing the year after a harsh winter kill event. Note the blind buds on the fruiting canes and that the suckers are generally the shoots that survived best. This might be a vine that needs to be retrained from a sucker on the base:

Figure 2: Vine Growth After Winter Kill

Here are a few suggestions on nursing winter-injured vines back to health:

- Agricultural molasses. I’m not kidding! Add soluble molasses to compost tea, or just glop some under the vine’s drip emitter. Works great to increase microbial activity to increase vine nutrient status after winter damage.

- Early nitrogen, zinc, calcium, and potassium will also help. Give the vines a strong fertilization as soon as leaves lose their milky, yellow color. (mid spring, early summer)

- Cut clusters off stunted shoots. I don’t leave fruit on any shoot with less than 10–12 leaves.

- If the vine is really hurting, try bringing up a sucker as a new trunk, or for full winter kill, replant and consider wine grape varieties a step more cold-tolerant.

Conclusion

Let’s step back from the brink for the moment. Maybe this has been frightening and you are now going back and forth through the emotions of excitement and worry. But if you’ve farmed for a while, you know that we can prepare and be vigilant, but “it is what it is” and there are times in farming where nature is inexhaustible in its cruelty. But, there is good news. Vines can take a lot of punishment and keep coming back — and I do strongly believe that vines that have been kept healthy always show less cold damage than vines that are struggling.

So do the things that keep your vineyard thriving in the growing season and it should help with the worst nights of winter — maybe the vines remember the excellent time they had with you on summer vacation! Good luck in those far northern (or far southern) latitudes this year and send me some ideas and pictures of the strategies that are working for you so I can share them.