A Year in a the Life of a Wine: Part II (Grape Processing)

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment of a year-long series of the life of a homemade wine, from homegrown grapes in New York State.

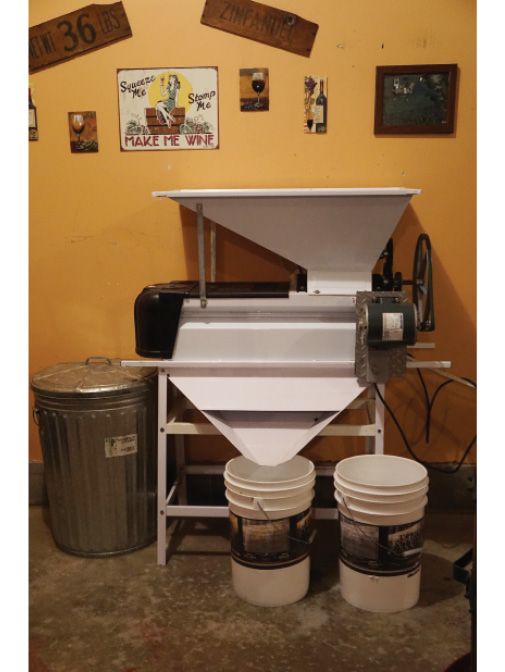

After harvest, the next phase of the life of my homemade wine is when I process the fresh grapes. The initial stages of my grape processing occur in my garage where I have a corner that is designated for crushing, pressing, and red wine primary fermentation.

Before any of this area and equipment gets used, however, I spend a day organizing the garage and cleaning and sanitizing all the winemaking equipment and tankage. I clean the entire concrete processing area and then rinse with sanitizer and water. All the equipment is also cleaned, and then sanitized with a sulfite and acid solution. Just this part of the annual grape processing is quite an event — and I do it by myself, I might add.

One big benefit to the cleaning and organizing stage is that it forces me to do my annual clean out of the garage (which seems to be everyone in the house’s dump zone for anyone who has a garage). I then set up a folding table for my grape scale and testing equipment. I set the tare weight for the harvest baskets, so I’m ready to weigh the incoming harvest.

I set up a table for my team of volunteer harvesters with all sorts of snacks like cheese and meats, crackers and bread, seedless table grapes from the vineyard, and plenty of bottles of last year’s wines for everyone to drink. In addition, for those that would prefer, plenty of homebrewed beer in the garage refrigerator. I started brewing beer as well, and many pros will tell you that it takes a lot of beer to make good wine!

Once processing begins, I start with my white grapes as they are the first to be harvested. I grow Vidal Blanc, and this French-American hybrid is a workhorse in my vineyard. It produces beautiful loose clustered grapes that allows for many winemaking styles in the winery.

Once the Vidal Blanc is picked, brought in by the basket, weighed and logged by the harvesters, I then run it through my crusher/destemmer and immediately put the crushed fruit into my basket press. The free run juice is collected and put into a cleaned and sanitized food-grade tank. Once all of the white grape juice has made it to the press, I set up the press and the group of us takes turns pressing.

There is something about squashing grapes that brings a sense of fun and joy to the group. Anyone who is interested gets a shot at the ratchet! While this is going on, I usually switch out the buckets frequently. I get a little protective of that juice that I worked all year in the vineyard to achieve, so I’m a little type A here. The pressed juice is added to the free run and the tank is covered and allowed to settle overnight.

Once the white grapes have all been processed through the crusher/destemmer, the harvesters start bringing in the baskets of red/black grapes. I grow five different varieties in my home vineyard: Two Cornell hybrids, Corot Noir and Noiret, University of Minnesota’s inter-specific hybrid Marquette, the French-American hybrid DeChaunac, and the native American variety Concord. Each one of these varieties has a specific destiny in my annual winemaking. Just like the Vidal, each basket is weighed and logged by the harvesters. The red/black grapes are run through the crusher/destemmer and then transferred to one of three cleaned/sanitized primary fermentation tanks.

Now is where I get a bit atypical from what many others may do at this stage in the process: I field blend my red grapes. Based on each variety’s specific attributes (flavor, tannin level, and acidity) I predetermine, well before harvest, how I will blend my grapes with the design of creating a well-balanced, complex, and interesting wine. Many other winemakers choose to vinify each variety separately and before bottling do a number of test blends to determine the best and final blend of their resultant wines.

Like making wine, I also love to cook. I have a philosophy that the best and most uniform flavors come from when, in the case of cooking, ingredients are allowed to cook together. I call it my “most flavorful stew concept.” Based on this philosophy, I like to field blend my grapes in an attempt to get what I feel is the most flavorful wine.

Now, being a cold-climate grape grower, I have limited myself to hybrids and native varieties. Vinifera varieties are just asking for problems and setting myself up for failure in my terroir. They require soil strata, growing season lengths, and warmer winter low temperatures that I just can’t provide. The question is, however, do I (or more importantly, does my wife) enjoy wines made from non-vinifera grapes? For us, they lack robustness. Most red wines we have tasted from New York, while well made, seem a bit thin, acidic, and lacking in finish for us. Making wines just from my home-grown red/black grapes, I can expect no difference. So what to do? This is where I coordinate with my local wine supply and grape supplier. Every year, I “design” what my red wines will be; I determine what attributes I want to bring to my dry red wine blends and based on what I know I will get from my home grown grapes, I pick varieties to buy from my supplier that will hopefully complement and build what might be lacking in my cold-climate grapes. I look to add grapes that can add tannins, sugar, and certain flavor profiles. So with those extra grapes, along with a ratio for the blends. I order the grapes from California, as the harvest dates somewhat coincide, and pick them up the night before, so they are waiting to be processed along with my home grown grapes.

My blends vary a bit, but are typically 40% homegrown De Chaunac, 30% California Cabernet Sauvignon, and 30% California Zinfandel. In my opinion, this makes for a robust, well rounded, balanced red wine that’s great with steaks and other red meat. My other blend is typically 40% California Pinot Noir (sometimes Syrah — depends if I want a “spicier” wine in any given vintage), 30% homegrown Corot Noir, and 30% homegrown Noiret. My Marquette is a newer planting, so this will be added to this blend in a few years to come. This blend results in a fruit-forward wine that is great for sipping; while complementing foods like pork, lamb, and tomato-sauce based dishes. They’re great with cheese and crackers too!

So the preselected grapes are all crushed, destemmed, and blended in the awaiting food-grade tanks. After about two to three hours of skin contact, I bleed some of the juice off of the two red-blend tanks. I typically bleed about 8 gallons (30 L) off of each; approximately 15%. I use this to make my rosé still and sparkling wines for the year. Not only do I end up with a different wine and style from these grapes, the bleeding of juice acts to further increase the skin-to-juice ratio of the dry red blends, enhancing color, flavors, aromas, and tannins of the resultant red blends. The rosé, like the white, is covered and allowed to settle overnight. All wines then get a dose of pectic enzymes. This helps to maximize the release of color and tannin from the red/black grape while assisting in the overnight clarification process for the white and rosé.

You might be asking, what about the Concord? Well that one greatly varies from year to year based on the blend. Concord, being so descript in its flavor profile, will always be the predominant aroma and flavor from the resultant wines. Each year this grape becomes the foundation for an off-dry Concord blend, a semi-sweet strawberry Concord wine, and a sweet fortified Concord Port. Maybe this will be the year for a sparkling Concord? Who knows!

The morning after processing, the next steps in winemaking begin. This covers everything from yeast selection (predetermined) and hydration, Brix, pH, chaptalization, fermentation temperatures, the list goes on and on, is taken into consideration. My next installment will cover the particulars associated with these decisions as we continue with a year in the life of a homemade wine.

The Vineyard After Harvest (sidebar)

During this stage of a grapevines’ annual lifecycle they go through a stage of rapid root growth to build up carbohydrate stores and hardening off their shoots to survive the winter cold. You can help your grapevines at this stage by giving them a heavy watering. If Nature has no plans in helping out with this, then you’ll have to step up. In my vineyard, I attached some inexpensive soaker hoses along the bottom wire of my trellis. By running the water for the bulk of the day, I ensure that all my vines get the deep heavy watering that they crave. These also come in handy during a very dry summer when you might want to provide a bit more water for your vines. For the cold-climate grape grower there is one more task that is very important. It is called hilling-up. This is especially important if you grow grafted grapes — varieties grafted to specialized root stocks to account for your soil strata and conditions. To accomplish this in my home vineyard, I run my tiller along the sides of each grape row to soften the ground. I then use a garden rake to mound this freshly tilled soil up around the base of each grapevine. The focus of this is to make sure there is it least three to four inches (7.5 to 10 cm) of soil mounded above the graft union. Hilling-up provides a level of freeze protection for one of the most fragile parts of the grafted grapevine. This procedure is even more critical in the first three or four years of a vine’s life. In the spring, these mounds will be brought down back below the graft union to ensure that no scion roots form. After this stage, I just wait for the first heavy frost that will defoliate the vines until next bud break. The hope is that there is enough time in between harvest and that frost for the grapevines to build up their stores so that they can have a very fruitful next season.