Backsweetening

The backsweetening technique offers much more than just making sweet wine. While that remains a primary goal for many home winemakers who do it, other applications cover a range from just taking the edge off a harsh vintage to making traditional-method, Champagne-style sparkling wine. Regardless of the specific project or objective, some of the basics of backsweetening remain relatively constant. After reviewing some features, we will look at specific applications.

Most homemade wines, particularly from grapes, are made and consumed dry or nearly dry — that is, with very low residual sugar. Threshold opinions vary, but a residual sugar figure of about 4 g/L (0.4%) or less is often considered the “dry” mark, with perhaps twice that level considered “off dry.” When made commercially, wines with higher sweetness goals are commonly stopped during primary fermentation. That process is very difficult to carry out on a home winemaking level, although I will address aspects of it later when discussing stabilization of backsweetened wine. Instead, the best alternative in many home winemaking projects is to ferment the wine as dry as it naturally goes, then add a measured amount of sugar to achieve the desired sweetness. Commercial winemakers, in most cases, are only allowed to use grape sugar for sweetening wine. Home winemakers can do that, too, but we are not restricted to it. Ordinary table sugar — sucrose — from cane or sugar beets provides a simple, delicious, and reliable sweetener.

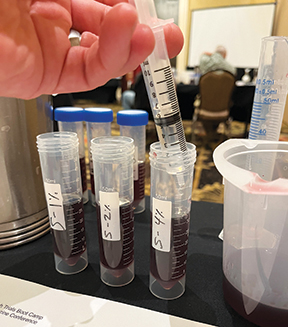

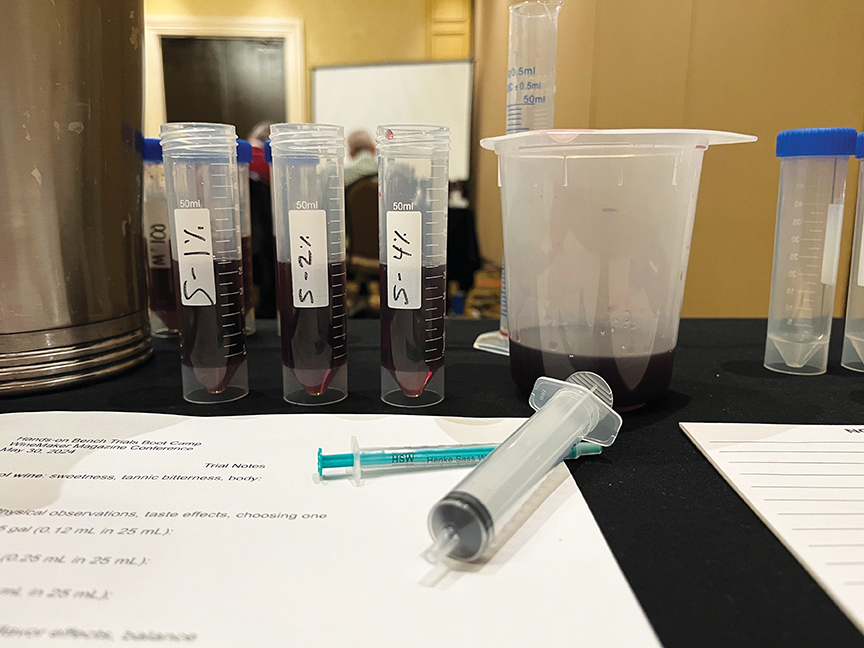

I always recommend bench trials for any sweetening project. Describing one such trial can serve as an outline for sweetening with sucrose. Rosé wines often taste fruitier and are more appealing with a low but measurable level of sugar. When my home vineyard produces an abundant crop of Pinot Noir grapes, I let the 32-gallon (120-L) bins of crushed must soak overnight, then make a carboy of saignée rosé by draining off a few gallons (10 or so liters) of juice before adding yeast to the remaining red wine must. From the drained juice, I produce a pink wine over just a few months and when it comes time for bottling, I do a sweetening trial.

The first step is to prepare my trial sweetening solution. I find it convenient to weigh out 100 g of table sugar, add 100 mL of distilled water, and simmer to dissolve. Let cool, then add distilled water up to exactly 200 mL. That provides a trial solution with exactly 0.5 g of sugar per 1 mL. As the solution cools, I thief out a full 375-mL screwcap bottle of the wine (topping up the carboy with compatible wine, or for very short-term storage, inert gas). I then measure 100 mL from that sample bottle into each of three more 375-mL bottles. The range of the trials is up to you, but for this sort of project I often sweeten to 1%, 2%, and 3%. The 75 mL still in the original bottle remains untreated and serves as the control sample for reference. Using my sugar solution, I add 2 mL to the first trial bottle, effectively adding a gram of sugar by doing so and achieving 1% sweetening. Then 4 mL and 6 mL go into the other trial samples. These measurements do not account for the slight dilution of the sample from the water in my sugar solution, but they are close enough for bench trial purposes. You can mix and taste right away, but more consistent results may be achieved if, after mixing, you place all four bottles in a dark cabinet overnight. In any case, get one or two other tasters to work with you, pour four tasting samples for each of you, taste, and discuss.

Having selected a winner, prepare the sugar for the entire batch. A 5-gallon carboy is close enough to 20 L for this calculation. So, if the taste trial winner was, say, 2% sugar, you will need .02 x 20 kg = 0.4 kg (400 g or 14 oz.) of sucrose for the whole batch. Dissolve by boiling in a minimum amount of distilled water. The volume of water doesn’t matter because you measured the sugar by weight. Boiling assures that the sugar has been sanitized and adding as a solution instead of as granulated sugar helps assure complete mixing. Rack the wine into a bottling bucket, stir in the sugar, stabilize, and bottle. Alternatively, rack to another carboy, stabilize, top up and hold for two or three weeks to make sure no unexpected reactions or fermentations occur, then bottle.

Stabilization Methods

I rather quickly glossed over “stabilize.” If you just add sugar to newly made wine, you will most likely get refermentation, cloudiness, and gas production. To avoid those problems, there are at least five ways to stabilize backsweetened wine at home. The one I use most often is the combination of sulfite and potassium sorbate. Potassium sorbate inhibits growth of yeast. It does not prevent bacterial growth, so sulfite is still needed with it. Wines that have viable malolactic fermentation (MLF) bacteria present must not be stabilized with sorbate as a geranium-like odor can be produced. My rosés do not undergo MLF, so I adjust the free sulfite level to about 50 mg/L (ppm) and add 1 g/gallon (3.8 L) of potassium sorbate. The sorbate is free of odor or flavor, so the wine should be sound and stable. If you’d like to backsweeten a wine that has gone through MLF use a product like Lysozyme or Stab Micro from Enartis to sterilize against bacteria and then proceed with sorbate.

Commercial wineries rarely stabilize with sorbate, perhaps because they would need to list it on the label. Instead, they most often use the second method a home winemaker can also use: Sterile filtration. If wine is passed through a filter membrane with an absolute pore size of 0.45 microns or smaller, and bottled in sterilized bottles, the presence of sugar should not result in refermentation or spoilage. These conditions are difficult to achieve and verify in home use, but with care (and accepting some risk) a home winemaker may find the procedure effective. Any sterile filtration should be the last step in the fermentation process to minimize risk of recontamination. Commercial wineries bottling sweetened wine will often have the filter on the bottling line, immediately before bottles are filled. They also do laboratory culturing on some of the finished bottles to check for regrowth before releasing the wine to the market.

The third stabilization method at home is very simple: Keep it cold. I have a draft beer system with three taps for 5-gallon (19-L) stainless steel kegs. I sometimes have hard cider on one of the taps and wine can be handled the same way. After I ferment the cider, I do sweetening trials. I rack the cider to a clean keg, stir in the measured sugar syrup, and put the keg in my kegerator set at 38 °F (3 °C). At that temperature and under a carbon dioxide atmosphere, the sweetened cider is very stable. The same approach could be taken with a sweetened wine.

The three stabilizations listed thus far have broad applicability to wine types. The remaining two apply to specific categories. The first of those is the méthode tradionelle used in production of sparkling wine. After still wine has been refermented with added sugar in pressure-tolerant bottles, the bottles are gradually tilted up and rotated over a period of weeks (riddled) to move yeast residue into the neck. On bottling day, the fully inverted bottles are placed in a freezing brine bath and a plug of ice, containing yeast residue, forms just behind the crown cap. The crown cap is quickly removed, the ice blows out, measured sweetening solution is added, and the bottle receives a Champagne cork. If the viable yeast has been successfully removed with the ice plug, the sweetened sparkling wine will be stable.

The final home method is fortification. When I make Port-style wines, I usually stop the fermentation with sulfite and near-freezing temperature with about 10% residual sugar remaining. That is not backsweetening, but if you were to instead add that much sugar to a dry wine, you might have something similar. To stabilize, the technique is fortification with distilled ethanol. Commercial wineries use “grape spirits,” which are sometimes called brandy but most often do not include the barrel aging of traditional brandy. For home use, any high-proof spirit that meets your stylistic goals can be used. If grape spirits are not available, high-proof grain spirits like Everclear sold in some parts of North America may be suitable. In Mexico, one can find high-proof alcohol de caña made from sugarcane. A finished alcohol level of about 18 to 20% ABV (alcohol by volume) in the wine is usually considered a stable fortified dessert wine. Use the Pearson Square method to calculate the needed ratio of base wine-to-spirit for a project like this. Learn more about how to use the Pearson Square online at: www.winemakermag.com/article/the-pearson-square

Sweetener Options

While corn sugar, also called dextrose or glucose, is often used in brewing beer to boost alcohol or add carbonation, it is not the best choice for backsweetening. Glucose is highly fermentable, but it does not taste as sweet on the human palate as either fructose or sucrose. Sucrose is inexpensive, widely available, and has a taste profile that people find pleasing.

If you prefer to use grape sugar to backsweeten your wine, liquid grape concentrate is an excellent choice. Using varietal concentrate also gives you an opportunity to add flavor nuances that may enhance your wine. To use, just look at the sugar content as listed on the label. Many are around 68 °Brix. The definition of degrees Brix is percent sugar by weight reported as sucrose. That means the concentrate as received is much like the sugar solution mentioned earlier for trials. The difference is the calculation, since each gram of concentrate contains 0.68 g of sugar instead of 0.5 g/mL. Adjust your calculation accordingly and weigh the concentrate for addition to the trials and, ultimately, to the whole batch of wine.

Reason to Sweeten

There are other times you may consider backsweetening beyond rosé, Port-style wines, or off-dry sparkling styles. Sometimes an otherwise well-balanced wine is just a bit too tart. You could try chemically deacidifying, but a simple improvement might be just a touch of sweetness.

Similarly, a wine’s tannin profile may leave it rough and bitter on your palate, but a bit of sugar may smooth it out. As long as you make sure to stabilize, you may not need other treatments to make just the correction you need.

Very often wines from fruits other than grapes don’t have quite the richness and complexity you are looking for. Backsweetening to the rescue! Fruit wines often don’t taste like we expect when the fruit’s sugar is fermented out. I remember making a pretty pink wine one summer from moon and stars watermelons that we bought at a local farmer’s market. The wine fermented well and looked nice, but when completely dry it tasted more like cucumber than melon. A bit of backsweetening with cane sugar brought around the juicy melon character and it was a welcome warm-weather sipper — especially over ice with a splash of club soda.

As I complete this column, I have a melon plant in my summer garden. The variety is Crane Melon, developed in the early 20th century just up the road from me in Penngrove, Sonoma County, California. Who knows? If yield is abundant, maybe harvest time will lead to another backsweetening taste trial.