Balancing Wine’s Structure: Techniques to add and remove tannins

In my June-July 2022 column on using oak alternatives, I mentioned tannin contributions among the benefits of winemaking with oak. In this column, we will both add and subtract tannins.

Tannin-rich materials were originally used in tanning hides; turning animal skins into leather. In wine, tannins bind with the proteins of your palate. Since that does not sound pleasant, why do we want tannins in our wine? They are often bitter and thus provide a balancing effect against the sweetness of fruit, sugar, or alcohol. Tannins can provide structure to avoid an overly soft impression on the palate. They stabilize color in red wines and provide antioxidant benefits in all wines.

Wine tannins come primarily from grapes and oak. When tannin extraction goes right, you have a balanced wine. If it goes wrong, you can have too little tannin or too much tannin. Low tannins manifest as soft and flabby with reduced color intensity in a red wine. If you get too much tannin in your wine, it can become harsh on your palate and astringent.

Adding Tannins

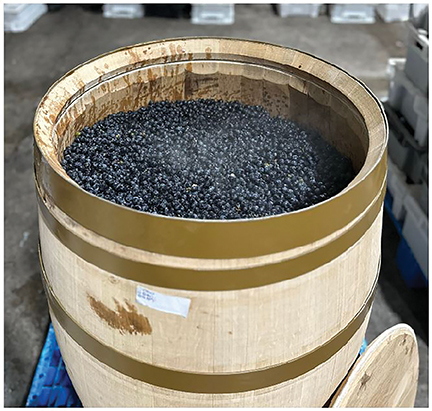

To increase tannins, you may start in the vineyard. Better sun exposure and a lower crop yield can improve the production of skin tannins. Once you have grapes, if the stems are well lignified (brown and woody), consider adding some back after crushing and destemming. You would typically return about 10% of the separated stems. If the stems are green, do not add any back. You can also try cold soaking your must to extract more tannins. Gas the fermenter headspace with inert gas, and keep the temperature below 55 °F (13 °C). You may be able to safely hold the must for two or three days before you allow the temperature to rise and begin your fermentation. After fermentation, you may be able to hold the must under similar protected conditions for extended maceration. Some winemakers find that such maceration styles extract more tannins.

Among grape tannins, those from the skins are favored. Crushing and maceration bring broken skins into contact with the juice. Seed tannins are harsher and you should avoid breaking seeds. If your red wines are coming out too tannic, consider removing seeds during fermentation. One way to do that is the process of delestage or rack-and-return. Drain the fermenting wine through a strainer, catching the seeds. Then pump or pour the wine back over the cap, discarding the seeds. Stem tannins are usually eliminated before beginning maceration. Or you can add a commercial grape-tannin product.

Tannins can provide structure to avoid an overly soft impression on the palate.

Barrels are the most traditional way to add oak tannins. Staves, sticks, cubes, and beans of toasted oak may also be added during wine aging. Oak sawdust can be added to a primary fermentation to provide “sacrificial tannins” that help stabilize wine color. Prepared tannin products serve similar purposes. For my red wines, I like to add Scott’Tan FT Rouge Soft. Other products include EnartisTan V and Tannin VR Supra. White wine tannin products, intended to help protect against oxidation and improve mouthfeel, are sometimes made from oak gall nuts. I use FT Blanc Soft and Enartis offers EnartisTan Blanc.

After fermentation, a wine can be augmented with other prepared products. Besides oak, chestnut wood and exotic woods are used. For white wine, there are citrus wood tannin products. Visit the manufacturers’ websites to learn more about the various products. Once you have a product, do trials at a mid-range dose before treating your wine. Weeks of aging may be required to completely integrate a product in your wine, but you can usually make a sound judgment based on an overnight trial. If you like what a product does for your wine, you can move on to adding it or do another trial to set the dose.

Removing Tannins

What if your wine is too harsh, bitter, or leaves a rough astringency on your palate? Often very young vines produce grapes without enough fruity character, leaving the tannins out of balance. Even in a mature vineyard, overcropping may cause excessive tannic character in the wine. Some varieties are inclined toward very tannic wines, even when fully ripened. These include Tannat, Petite Sirah, Cabernet Sauvignon, and others.

The same steps described earlier to increase tannins can overdo it in some cases. A very long cold soak, too many stems added back, or excessive extended maceration on the seeds may cause a tannin overload. Adding too much tannin product can leave you with a problem.

There are three ways to reduce tannins in astringent wine. These are bulk aging, bottle aging, and protein fining. Bulk aging in barrels is traditional for red wines around the world. A barrel can allow slow and gentle oxidation reactions to occur in aging wine. Tannins polymerize into longer chain molecules that have a softer impact and may drop out entirely. Tanks and carboys may not have the benefits of oxygen addition, but they can allow the polymerization of tannins. Wine will also continue to mellow in bottle. While you may like such a wine better after two, five, or even ten years in the bottle, it may come with a side effect: Precipitation of tannin residue in the glass.

Protein fining is the active way to remove tannins from a wine. Protein additions bind with tannin molecules, precipitate out, and are left behind when you rack off. The intended result is a softer profile, reduced astringency, and a rounder effect on the palate. The primary goal is tannin removal, but some of the proteins react with oxidized wine components and may freshen the overall profile as well. These fining agents are not intended to improve clarity, although that may occur.

There is some risk of “overfining” with proteins. That manifests two ways: Either so much tannin is removed that you now need a tannin addition, or there may be excess protein left in the wine leading to haze and cloudiness later on. The traditional protein fining agents are all of animal origin. Although there should be very little fining agent left in the wine, people on a vegetarian or vegan diet may prefer to avoid these products. More recently manufacturers have introduced some vegetable protein finings.

The four common animal-derived fining agents are egg white, casein, isinglass, and gelatin. Egg whites are just what you think, the whites of chicken’s eggs separated from the yolks. Casein is the protein found in milk. Isinglass is a protein product derived from the swim bladders of fish, traditionally sturgeon but other species are also used. Gelatin is from the same origin as the gelatin used in making desserts. It is produced from animal bones, hides, and tendons—usually from pigs. For using any of these, do a trial first.

Egg White Fining

To fine with egg whites, separate yolks from whites and reserve the yolks for another purpose. Egg whites can be added directly to barrels, although more often they are lightly beaten with a little water and wine. Add a pinch of potassium chloride and avoid beating so stiff that they float on the wine.

To treat a 5-gal. (19-L) batch, separate one fresh egg and take half of the white. Beat that lightly with a pinch of potassium chloride, a little wine, and a little water. Stir into the wine. Let the wine stand until clarity returns, usually just a few days. Rack off of the tannin and egg white sediment.

Casein Fining

Casein may be applied in several different ways. If you start with powdered casein, you will need to start by rehydrating it under alkaline conditions. Easier is to use potassium caseinate, which readily dissolves in water. You can use nonfat milk or whole milk directly. Since casein removes some browning along with tannins, it can improve the color of brownish white wines. It softens the tannins of red wines, but not as aggressively as gelatin. Nonfat milk has an advantage over potassium caseinate in that it adds a small amount of lactose to the wine, so you get a slight sweetening effect that may offset some of the bitterness you are trying to correct.

Whole milk offers the same sweetness, and its fat may absorb some other off-aroma compounds like TCA (cork taint) or even smoke taint from wildfire smoke exposure. Take care if you use whole milk to rack within just a few days and separate the wine from both the sediment and the floating milk fat.

For packaged casein products, follow package instructions. To use milk, add up to 250 mL directly to 5 gal. (19 L). Note that for commercial U.S. wines TTB (the Tax and Trade Bureau) limits milk additions to 0.2% of volume, or 40 mL in 5 gal. (19 L). In home winemaking, higher doses may be beneficial and dilution of the wine is not a market concern. Rack in about four days from any casein fining. If a haze remains, you may need to counter-fine with bentonite or tannins.

Isinglass Fining

Isinglass is less effective against astringent tannins than the other proteins and has less tendency to over fine. However, it does have bulky lees leading to potential loss of wine volume. If not very fresh, it can also develop fishy odors. Follow package directions — sometimes an acid addition or soaking may be required. For 5 gal. (19 L), a typical approach is to add one Tbsp. (15 mL) of granules to two cups (500 mL) of water with ½ tsp. (2.5 mL) of citric acid. Let stand 30 minutes then stir into wine. Let settle for two or three days and rack off.

Gelatin Fining

Gelatin is the strongest of the protein fining agents so use it if you have a very tannic wine you are trying to tame. Gelling strength is reported in Bloom units. Enological gelatin is about 80 to 150 Bloom, while dessert gelatin is about 175 to 275 Bloom. Gelatin is so strong that it may strip the wine of desirable characteristics. It may also require counter-fining with tannin to restore balance. To treat 5 gal. (19 L), dissolve ¼ ounce (7 g) in 10 oz. (300 mL) of hot water. Let stand 10 minutes and stir into wine. Rack when clarity returns.

Protein Fining For Vegetarians/Vegans

While some vegetarians may be comfortable with casein or egg whites, vegans probably will not want to use any of the traditional proteins. For them, or anyone else who is curious about it, I recommend trying one of the new pea-protein products. One example is Enartis Plantis AF and others are coming to market to meet this emerging demand. The products are entirely free of animal materials, they remove tannins, and may aid clarity.

To treat 5 gal. (19 L) with Plantis AF, suspend two to six grams in ten times as much water. Stir the suspension into the wine or mix while racking. Let settle and rack. Treat with bentonite if complete clarity is not restored.

So now you can go up or down with your tannins. Rely on your taste and the advice of trusted helpers to decide if you need to make a change in the wine’s tannin profile. Select possible products to add or subtract and run trials before treating a whole batch of wine. Upon choosing a material and a dose, then you can make the addition to the whole batch. But remember, time can also be used to treat a wine that has excess tannins. Patience in this sense can be a great virtue. Enjoy your improved wine!