Co-Fermentation: Tips From the Pros

Winemakers most often ferment each grape variety separately and then create blends after conducting precise blending trials. However, some winemakers believe fermenting varieties together results in more complex wines.

Michael Bairdsmith is the Assistant Winemaker at Ridge Vineyards’ Lytton Springs, California

We co-ferment Zinfandel along with Petite Sirah and Carignane. The Petite Sirah lends some weight, tannin, color, and dark fruit character, while the Carignane contributes bright red fruit character and vibrant acidity. We also do a small amount of Syrah that we co-ferment with Viognier, which is a common practice in France’s northern Rhône region.

We farm a number of estate vineyards that were planted well over a century ago. It was common practice back then for California grape growers to deliberately plant various varieties intermixed in the vineyard. For instance, our Lytton Estate – East vineyard is broken into 18 blocks, and years ago we went through and identified every single vine in the field and were able to assign a percentage of each variety to each block. For example, a block we’ve designated North Flat 1 is planted to 85% Zinfandel, 5% Carignane, 5% Petite Sirah, 3% Mourvèdre, and 2% Alicante Bouschet. Another block designated Hill 3 is 75% Zinfandel, 25% Petite Sirah.

As part of our commitment to traditional, or “pre-industrial” winemaking, we honor the practice of planting a mixed bag of grape varieties by picking whatever is planted out in the vineyard all together. This is known as a “field blend.” When we decide to harvest we’ll pick all the different varieties within the block together and co-ferment them.

There is some kind of alchemy that happens when you co-ferment. A number of years back we harvested one of our vineyard blocks in two ways. We first went through a portion and picked the Zinfandel, Carignane, and Petite Sirah separately. We then went through the rest of the block and picked everything together like we normally do. We then fermented the three varieties separately and blended them after the fact and compared the results of that wine against the co-fermented wine in a blind tasting. Literally everyone participating in the tasting preferred the co-fermented wine. The most common reason given for the preference was “greater complexity.”

At our Montebello location where we produce our Bordeaux blends we ferment varietals separately. The main reason Bordeaux varietals are better suited to blending post-fermentation is that, particularly in cool-climate regions like the Santa Cruz Mountains, the grapes ripen at different times. Here at Lytton Springs things tend to ripen all at once. There may be an argument that the small amount of Mourvèdre in a block is going to be well behind the Carignane, but their ripening times are not so disparate to have a negative impact on the resulting wine. In fact, a little variation in ripeness within a block may even be part of the alchemy that makes co-fermented wines special.

Just because you’re co-fermenting doesn’t necessarily mean you have to pick all at once; there’s nothing in the rulebook that says you can’t add new grapes to already fermenting grapes. If, for example, you’re making a Zinfandel at home and it’s halfway through fermentation but you’re not getting the color you want, go find some Petite Sirah and toss it in the mix.

I think anyone making red should consider co-fermenting with a little white thrown in the mix. It really works wonders when it comes to aromatics and acidity. And if you’re looking for a bit more structure and color in a home wine, a little Alicante Bouschet goes a long way.

Jason Phillips is the Winemaker at Jumbo Time Wines in Los Angeles, California

Recently we have co-fermented Syrah with Mourvèdre, as well as a fruit wine of Sauvignon Blanc with pears. Previously we’ve done Pinot Noir with Chardonnay, Carignane with apple, and Carignane with pear.

The only combination we’ve repeated so far has been 50/50 pear-Sauvignon Blanc. It hits a nice balance of ABV, acidity, and residual sugar, so we’ve decided to stick with it. Whether or not we co-ferment often depends on the vintage and if both varieties are ready to be picked at the same time.

The benefit of co-fermentation is that there’s likely to be greater complexity and a more seamless integration to the finished wines. We’ve never done an experiment where we do the same grapes co-fermented and blended, it’s just a feeling from experience tasting co-ferments versus blends.

If the harvest dates line up, we’ll always be interested in trying co-fermentation. We have to choose a harvest date that works for both varieties. So, often you have to split the difference and one variety might be slightly over or under your ideal ripeness. Sometimes this gap is too big and the logistics just don’t work out to do a co-fermentation. Don’t force it. If the grapes aren’t ready to be picked at the same time then it’s not likely to work out well.

I’d consider co-fermenting anything that you plan on blending. You have to give up a little control, but the results can be interesting.

Cardiff Scott-Robinson is the Winemaker at Paraduxx in Napa, California

We typically co-ferment Syrah and Viognier. This is an Old World style of winemaking that we implement at Paraduxx for our Winemaker Series Co-Ferment Napa Valley Red Wine.

Co-fermentation is not usually a standard practice for us other than with this Syrah/Viognier blend, but this past year we co-fermented some Petite Sirah and Zinfandel and had great success. Petite Sirah is a very tannic grape, and Zinfandel can be very juicy and fruit-forward. We were pleasantly surprised how the Zinfandel tamed the big, bold tannins of the Petite Sirah and made the post-fermentation wine smoother and more complex. We enjoyed the result with these grapes so much it may become a standard practice for us going forward.

The determining factor of how much Viognier we used in these co-ferments for many years was our supply of Viognier. We only had a limited supply from our estate ranch, with the majority used for our Proprietary White Wine. Recently, we acquired another vineyard with a small block of Viognier on it, which has allowed us to increase the amount of Viognier we can co-ferment with. The 2019 vintage of the Paraduxx Co-Ferment Red Wine had 7% Viognier, with 84% Syrah, and 9% Grenache.

When co-fermenting Viognier with Syrah, the Viognier will naturally stabilize the Syrah’s dark purple red color and make it appear almost glossy and bright while softening the larger tannins Syrah can contain. Additionally, it will add aromatic complexity to the wine. Putting a glass of dark red wine to your nose and getting white flower aromas can be perplexing yet alluring at the same time.

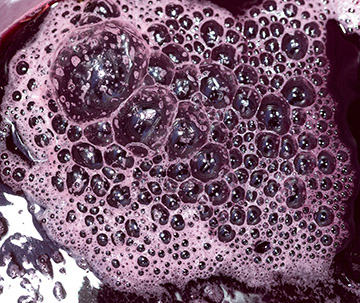

We use specific yeasts and fermentation tanks for certain wines. Since our typical co-fermentation is with Syrah and Viognier, we tend to ferment this in an open top, which allows more oxygen into the fermentation. We are using a pneumatic punch-down device that is very gentle in terms of extraction and a yeast strain that accentuates floral notes to increase the aromatics.

All of our other wines are fermented and aged as separate varietal lots and then blended pre-bottling. This allows far more control over the flavors we strive to highlight in the final product. We can always do blend trials and see if we want more Cabernet Sauvignon in our Zinfandel.

Winemaking is exploration. You don’t really know if it is worth it unless you try. Start small. Be curious and adventurous. That is what makes winemaking fun!