Making Age-Worthy Wines

When I work the tasting room, one of the most common questions I get is how long a particular bottle of wine will “lay down for?” I usually quip that it depends on how thirsty you are and whether it is the last bottle of wine on Earth or something stupid like that. It is a valid question for the serious collector, but many of today’s wines are made to be consumed right away because that is what the wine-buying public is used to. Presenting a wine to a potential customer and telling them not to drink it for five years is not a good selling point for the average customer. I prefer to let our customers know that they can drink the wine when they get home or that it may lie down for five to seven years. I want them to be pleasantly surprised when they open the bottle. I can’t count the times that I’ve opened a bottle and been disappointed that I had not opened it earlier.

Just recently I opened a 2017 Pinot Noir from Oregon with a screwcap closure, and it was absolutely dead! The replacement was a 2017 Pinot Noir from California with a screwcap closure that showed well, but not great. It was good enough to finish our meal though! It also reminds me that the overall age-worthiness depends on several factors — the grape variety and how it is grown, the winemaking process, bottling conditions, closure type, and above all, the conditions the wine is subjected to during aging.

Many grape varieties, white or red, have aging potential. I have tasted 50-year-old Semillon wines from the Hunter Valley of Australia that were superb! A 20-year-old Chenin Blanc from France’s Loire Valley that had never seen the light of day since going into the bottle was of equal quality. And I’ve experienced the “trendy” and modern California Cabernet Sauvignons, generally considered to be an age-worthy wine, falling flat after 3–4 years in the bottle. I admire the Cabernet-Merlot blends of the late 1990s where the wines were made with the tannin and acid structure that lends itself to aging. Which leads me to the topic of this column: How do you make an age-worthy wine?

Ageability Starts with the Numbers

Let’s first address the grape variety. Our readership works with hundreds of different varieties from around the globe. I have always advocated great wine begins in the vineyard, but we cannot apply what makes an age-worthy wine based on California-grown grapes as compared to a wine from Michigan, Virginia, South Africa, or Australia. Because the wine’s life begins in the vineyard, your harvest picking decision is important. Too early, and you have high acid. Too late, the opposite with too high of tannin maturity and sugar levels. There is so much to think about upfront. Ultimately, you are aiming for the common factors of any grape and how it is incorporated into the winemaking process. Notably, pH, acidity, and the tannin content of the resultant wine. What affects these parameters are the winemaking process itself.

Starting with pH, defined as the “negative logarithm of the molar hydrogen ion concentration in a solution such as wine and must.” So, what does that have to do with wine? It is very important in that the overall pH affects the flavor differences and compound reactivity in wine, as well as its risk of spoilage. Typical pH values in wine grape juices and wine are 3.2–3.8, with values less than this range more common in colder growing regions, and possibly underripe fruit, and greater if the opposite is true. Higher pH also results in less effectiveness of sulfur dioxide and more opportunity for spoilage organisms to gain a foothold.

Moving to how the wine tastes, while acidity is related to pH, it is a separate parameter and directly affects the perception of wine in the mouth. Higher acidity results in a “puckeriness” in the wine, and lower acidity is generally a wine with no mouthfeel. You can generalize that high-acidity wines have lower pH, and low-acidity wines have a higher pH. Not always the case, but the exceptions are more complex to work with and the subject of another article. Targeting a specific acidity value, or “winemaking by the numbers,” does not always result in balanced wine. It is not possible to tell you that a wine of pH 3.5 and acidity of 6.0 g/L will be the best age-worthy wine in the history of winemaking. It’s the balance between the two parameters that is most important, plus tannin perception.

The tannin content of a wine is a function of the grape and the winemaking process itself. A majority of the tannins in red grapes are located in the skins and seeds, so your maceration process will directly affect the resultant perception of bitterness and astringency. In the corporate world, we used a few different analytical techniques to quantify the tannins, but in the end, the only generalization I saw was low versus high, but it was the winemaking that balanced the overall wine.

How do you craft or identify that wine you want to age? It is all about perception and balance. Perception is defined as the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information to represent and understand the presented information or environment. Balance is having the right amount — not too much or too little — of any quality, which leads to harmony and evenness. Understanding the role of pH, working to balance acidity and tannins, and understanding how some residual sugar can balance out the final wine are all key. As a home winemaker, with limited access to analytical resources, much of this revolves around the art of tasting.

When making the wine, from grape receipt to bottling, you should always be thinking about where you want this wine to be perceived in three months. I think in the short term because wine is a biological transformation and needs to be evaluated often. So on the arrival of the grapes, I am looking at the pH and acidity mostly. These are analyses that most can do easily. Check your pH and acidity.

In the case of low pH and high acidity, wait and see what shakes out after the alcoholic fermentation. Often, in this generalization, moving the wine through the malolactic fermentation (MLF) is necessary. In the case of high pH and low acidity, I am adding tartaric acid to drive down the pH prior to fermentation. My target pre-fermentation pH is somewhere between 3.3 and 3.5. Experience is the key here — there’s no real recipe given that all wines are different in their buffering capacity. In the background I am thinking of what the actual malic acid content was to start with, but once again, limited resources put my palate back to work. My next look at pH and acidity is after the alcoholic fermentation and MLF, where it is time to do bench trials to make a final adjustment before you begin the aging process. At this point you are generally looking at mouthfeel and perception — hopefully you estimated correctly and have a pH lower than 3.7 or so.

A wine with higher acidity might warrant a chemical de-acidification with potassium carbonate or balancing with residual sugar. Lower acidity requires acid trials and evaluating the acidity perception in the mouth, with pH now being a secondary importance. Driving the pH down here is the most common slip in winemaking as it will lead to an unbalanced wine that is difficult to correct.

Where do the tannins play out? They are important to the overall aging of wine. From a chemical standpoint, while aging, tannins move from short chain compounds, which are perceptibly more bitter or astringent, to longer chains through the process called polymerization. This results in a perception of the wine becoming “softer.” High-tannin wines need more time to age and soften. But too much tannin and imbalance of the pH/acidity scheme result in the wine not being age-worthy.

Since tannins are contained mostly in the skins and seeds, I focus on more gentle ways of processing the fruit. My philosophy is to avoid putting something in the wine that I am going to have to take out later. Investing in a destemmer/crusher with adjustable rollers is a way to modify your initial maceration based on the grape variety received. Removing the stems first will decrease the amount of green tannin that can be extracted if the stems were run through rollers. I will set the rollers close together to increase the fracture of the skin when processing grapes lower in tannin, but not so close the seeds are damaged. I open the rollers wider when crushing grapes higher in tannin to allow only minor berry fracture. This type of equipment is available to the home winemaker, but does come with extra costs. A basic destemmer/crusher, like Enoitalia, runs in the neighborhood of about $2,500–$3,000, but for about half that price Enoitalia makes a crusher/destemmer with self-adjusting rubber rollers. As the whole clusters pass through the rollers, springs move the rollers in and out based on the cluster size, minimizing damage to the stems. The important part here is to recognize the impact the way the fruit is processed has on the outcome of the wine.

With respect to the maceration process, a cold soak (below 45 °F/7 °C) done before you initiate fermentation yields some benefit in color extraction, but those conditions are difficult to maintain without some form of temperature control and keeping the headspace free of oxygen. Alternatively, an extended maceration that is greater than 10 days does not result in increased color, rather it increases the amount of seed tannin, which is a significant contributor to bitterness and astringency. Also, you have the challenge of headspace control to prevent oxidation. Coming out of fermentation there are many aldehydes present that can easily get away from you. So I see little advantage to either. I prefer my red fermentations to be simple by leaving them on the skins for only 6–10 days.

Techniques for Ageability

The emphasis to this point has been on the grapes, processing, and fermentation leading to the perception of where you want your wine to be in three months. Other challenges are making sure you have a clean fermentation with respect to temperature control and healthy, well-fed yeast.

Wine stability after fermentation is a combination of several factors. Sulfur dioxide stabilization and management, headspace control, temperature maintenance, and bottling conditions. All equally important because even the most carefully crafted wines through the maceration and fermentation process will suffer if not aged properly.

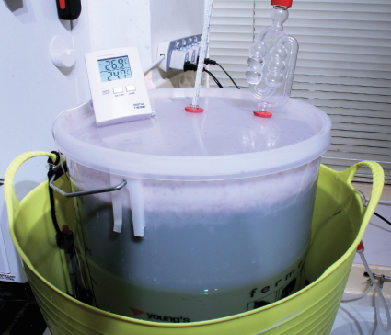

Getting a handle on sulfur dioxide early after fermentation is key to long-term stability. I prefer to be a little aggressive in my initial sulfur dioxide dosing being anywhere between 35–50 ppm (mg/L). The next addition comes after the first measurement of free SO2, about two weeks later. Do not be surprised if your initial results are somewhere between 15–25 ppm. I will then work to stabilize the free SO2 to between 25–35, with 2–3 more targeted additions. Usually by the third addition I have my target and work more in a maintenance mode until bottling of about a 10-ppm addition every two months. The wines should show no biological activity such as gas production or surface films if properly topped up every 3–4 weeks. Equally important is a constant temperature (no major swings on a daily basis) not exceeding 65 °F (18 °C). I like to call this the “review of the wine’s history.” Done correctly, its history should be a nice and pleasant rest in the cellar prior to bottling.

For bottling, some factors have to be considered — that aforementioned history and how much do you have to bottle? A history where the wine that had challenges with SO2 management, temperature, or headspace likely are not the wines you want to try long-term cellaring on. Bottle them and drink them while they still taste good.

A clean history and good balance with the acidity, pH, and tannin gives a wine a better chance at improving with age. It’s hard to quantify, but you can taste the quality, and it’s time to share that for a few years to come. Choose your closure carefully. I find that a good quality cork goes a long way towards a wine that will withstand the proper cellaring conditions. Your local winemaking store often purchases surplus corks and re-bags them in lots appropriate to the small volume winemaker. The result can be corks that are rock hard and have lost their coating. Look for corks that still maintain their softness. You should be able to compress them a little. You can be picky! You have worked too hard up to this point to put your wine into a bottle and have it spoiled because of closure failure. The bottle geometry does not matter, as long as the wine can be protected from light during aging.

Crafting an age-worthy wine is not easy and not all wines will age gracefully even in the most pristine conditions. You can control for them, but you are only human, and the wine is above all . . . wine. You win some, you lose some. I am reminded of a colleague of mine, when giving a presentation on old wines, who told the story of some of the best châteaus and vintages of Bourgogne and Bordeaux that were carefully crafted and cellared under most stringent conditions. He finished the story by telling everyone, that once you pop the cork, what you have is “just another bottle of wine.” I wish you success in your aging decisions.