Oak and Barrel Dynamics: Do’s and don’ts when it comes to wine and oak

Barrels are one of the most ubiquitous tools in winemaking, and one of the first things that come to mind when we imagine a winery: Rows of them, stacked high, filled with wine waiting for the bottle. Despite their near-universal use in winemaking today, they’re actually a relatively recent addition to wine, replacing clay amphorae, used for thousands of years before wood. Their most obvious contribution to wine is oak aromas and tannins, but barrels do much more, particularly with their ability to aid structuring. They also require the most care compared to other wine vessels and require diligent care to maintain. There’s a lot that goes into barrels — no pun intended.

HISTORY OF BARRELS

For the vast majority of wine’s 9,000-year known history, clay amphorae were the dominant vessel. Oddly shaped and cumbersome, it’s a wonder they were so widespread. There is a reference to palm casks being used for wine in Babylonia in the fifth-century BCE (Younger, 138), but it was not until the Romans, perhaps around 0 CE, that barrel use became more widespread. Roman barrels were much longer and thinner than what we use today; modern barrel dimensions came to be in the 1500s (Jackson, 582). Historically, barrels weren’t only used for wine, but for transporting all sorts of goods like salt and fish.

THE WOOD

Today, most barrels used for winemaking come from French oak, always white oak, specifically from Quercus robur and Quercus sessilis species. Q. robur is considered to lend more tannin (Smith, 62), while Q. sessilis is thought to give more aromatic compounds (Jackson, 583). Q. robur generally has a coarser grain, Q. sessilis finer. These characteristics aren’t always the case, and may reflect differences in each species’ preference for different growing conditions, and the result from these growing conditions on tree characteristics, rather than actual genetic differences (Jackson, 584).

Oak for barrels come from various forests around France, such as Allier and Tronçais, Nevers and Bertranges, Jupilles, Chatillon, Vosges, and Limousin. Usually barrels will have an initial on their head denoting the forest where the oak was harvested, for example, “A” for Allier, “T” for Tronçais. Vosges is thought to give more tannins, Tronçais to have a fine grain and give supple tannins, Jupilles to give an elegant and floral aromas (Artisan Barrels).

This is not to say that wine aged in the same type of barrels will turn out the same. There is a great degree of variation tree-to-tree within the same species or forest, even from different sides of the same tree, and therefore every barrel is different — so all of the above should be used as a loose guide, not definite. Either way, wine in different vessels will always age differently.

Although French oak is the dominant wood used for wine barrels today, this is also new; Central Europe was the preferred source for wood until World War II, when France was cut off from trade to that region. Central European oak is having a resurgence in popularity lately, and may be thought of as an intermediate between French and American oak characteristics.

American oak, from Quercus alba and related species, also sees some use today, although it is only widespread in parts of Spain and with a handful of domestic producers. Rioja is known for using American oak, although French oak has gained popularity there. Sherry is also famous for using American oak barrels, however, they are used for wine to be turned to vinegar for 10 or more years, as to not impart any oak character when used for actual Sherry. American oak tends to impart dill aromas, but this is not always the case. Also, historically, chestnut, acacia, redwood and others were used, and some modern winemakers are again experimenting with these woods, looking for alternatives to oak.

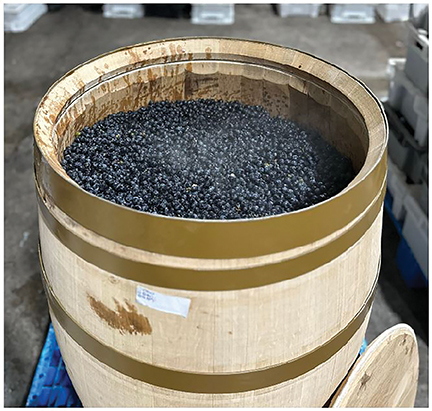

MAKING BARRELS

Making barrels is a very wasteful process. Because barrel staves can only come from about 25% of the wood harvested, most of the tree is simply thrown away. The trees used are often 200 years old (Smith, 63). This is obviously not sustainable and is one argument for keeping barrels forever and using oak adjuncts, like chips, for flavoring — not new barrels.

Staves are cured outside or in kilns for a minimum of 24 months. Some producers work with rainwater, others irrigate the oak during the curing process. As intense oak character has fallen out of vogue, curing times are getting longer to leach out and break down more of the tannin and aromas from the wood.

Although French oak is the dominant wood used for wine barrels today, this is also new; Central Europe was the preferred source for wood until World War II . . .

Once cured, the barrels are made. Fire is used to make the staves easier to bend, and once the body is constructed, the young barrels are toasted to differing degrees. Toasting barrels is a relatively new practice, and the earliest documentation of toasting dates back only to the mid-19th century (Jackson, 591). “Moderate toast can bring out spice elements that accent mouthfeel. Very heavy toast can produce deep espresso notes, which frame fruit well and enrich flavor persistence in the finish” (Smith, 62). “High temperature is necessary to create clove spice, vanilla, caramelization and espresso aromas” (Smith, 63). In addition to the initial for forest, barrels usually carry an abbreviation for the toasting (“MT” for medium toast “MT+” for medium toast plus, and so on). There is no industry standard for toasting, so what is medium for one company may be very different from another (Jackson, 592). Also something of note, heavy toasting may create compounds in barrels that can feed Brettanomyces yeast.

WHAT BARRELS DO: AROMA

The first thing most folks think of when it comes to barrels and winemaking is the oak aromas they can impart. This is definitely the most apparent of its effects, and one that sparks much controversy. More than 200 aroma compounds have been found to come from oak (Jackson, 599). Oak aromas can lend the perception of sweetness to a wine.

When oak is new, the aromatic contribution to a wine can be significant — and should be used with caution — although this depends on the wine. Some wines have an ability to age in new oak without being overwhelmed by it, whereas another wine might. It’s often thought that wines with sturdier structures can handle more new oak without showing an extreme oak character. The aromatic contribution of oak becomes less and less over the first few years of use, and is considered “neutral” after four or five years.

New oak (or heavy-handed use of oak adjuncts) can overshadow the character that comes from the grapes, making the star the barrel rather than the vineyard, which is what causes the controversy. Many famous wineries in the 1990s and 2000s relied heavily on oak for their wine’s character, some even being aged in “200% oak,” where a wine spends a year in new oak, and then a second year in another set of brand new oak barrels! Whereas yesterday’s trend was for extraction, richness, intensity, and big oak, wines whose character predominantly came from getting grapes very ripe and winery practices (like heavy oaking) — today’s trend is for wine to be “made in the vineyard.” This means picking earlier and avoiding practices that might overshadow the grapes’ natural terroir. It’s a valid point that oak can overshadow vineyard character, but stylistic preference is, of course, subjective — we like what we like!

Less known is that in addition to adding flavors, oak can also take them away. Oak can absorb fruity esters from wines (Jackson, 601). Although esters mostly break down on their own over the first year to 18 months of a wine’s life, for those looking to craft early-drinking, fruity wines, oak may best be avoided. Oak may also reduce greenness in wines (Jackson, 601). Our understanding of the aromatics that oak may remove is far from complete, but it is thought to reduce many aromatic compounds in wine.

WHAT OAK DOES: TANNIN

Oak, especially when new or young, can be an important source of tannins for wine, but they are mostly a different type and never as significant as those that come from the grapes. The tannin that comes from grapes is primarily condensed tannins, oak tannins are mostly what are known as hydrolysable tannins. Oak’s hydrolysable tannins have been found to reach a maximum concentration of 0.25 g/L, whereas grapes’ condensed tannins are much more significant, ranging from 2–4 g/L (UC-Davis, Waterhouse Lab page).

Oak tannins are structurally very different from grape tannins, and do not contribute in the same way to mouthfeel as grape tannins do. Oak tannins are much less astringent (the typical tannin-y sensation, a dryness in various parts of the tongue or mouth), but are bitter (giving a grainy sensation on the top of the tongue). High levels of oak tannins have been found to increase roundness in the mouth and decrease fruitiness (Jackson, 600), which grape tannins can do as well.

The tannins that come from oak can be beneficial for wine structure, color stabilization, and longevity. Barrels known to donate more tannins to a wine may be useful for low-tannin wines, Pinot Noir for instance, which may “benefit from substantial help in the form of oak antioxidants, color stabilizers, sweetness, and mouthfeel contributors” (Smith, 60). For both oak aromas and tannins, in Clark Smith’s essential book, Postmodern Winemaking, he makes the wise suggestion to select oak type not based on one’s preference for oak aromas or tannic wines, but based on the deficiency in the wine you are working with — Q. robur barrels that give more tannin for tannin-deficient Pinot Noir, or Q. sessilis barrels for grapes which may lack fruit or sweetness, such as Mourvèdre, Carignan, or Cabernet Franc (Smith, 59). For him, the importance of oak and oak choices is to help a wine express itself better, not to flavor it. Both oak aromas and tannins can be achieved by oak adjuncts. They are a cheaper, more sustainable, and more option-rich way to go (as far as wood type and toast levels) compared to buying new barrels.

WHAT OAK DOES: PERMEABILITY

The one thing that barrels can do that oak adjuncts and most other vessels cannot, is a slight degree of microoxygenation and releasing off-odors. Standard 225-L (60-gallon) barrels provide about 1 mg per liter per month of oxygen to a wine. Just after fermentation, highly structured red wines may be able to absorb and integrate into their structure 60 times this amount, although this decreases significantly as the wine ages. After a few years in barrel, this 1 mg/L/month would be too much (Smith, 98). While it may be much less than a young red wine wants or needs, oak does provide some degree of oxygenation to avoid reductive odors and help color and tannin polymerize more efficiently than they otherwise would in an impermeable vessel like glass or stainless.

Various factors affect how much oxygen will enter a barrel. Smaller barrels will give more oxygen — as well as more barrel extractives — owing to the smaller amount of wine relative to their surface area than larger barrels. Larger barrels have the opposite effect. New barrels allow more oxygen in than older barrels. Tightly bunged barrels allow less oxygen in than loosely bunged barrels — the bung may be the point where most oxygen enters barrels, as little is thought to actually enter through staves. Staves, however, do allow for alcohol and water evaporation, and allow for the release of off-odors.

CLEANING AND STORING BARRELS

Prepping new barrels can be done with the standard three-stage cleaning — sodium percarbonate wash, citric acid wash, water rinse. Cleaning used barrels is a bit more involved as there are built up tartrates and lees to wash out. It’s best to use a barrel washer, which has a rotating head that ensures that each part of the inside surface is washed. Barrel washers that attach to garden hoses can be purchased online for about $200. Be sure to buy the appropriate attachments to connect your hose. These basic washers are not for use with pressure washers, which requires a more elaborate barrel washer. The barrel washers that attach to garden hoses are at about 60 PSI, whereas the pressurized ones can reach 1,500 PSI — so the difference in their cleaning abilities, as well as price and what equipment you need to use them, is big. The garden hose attachments are more of a really thorough rinsing, to spare your back from shaking the barrel around. The pressurized versions will blast out most tartrates. If tartrates do build up, you can wash with sodium precarbonate, followed by a hot water rinse. Just make sure you do a citric wash before putting wine back in. After washing, you can do a three-stage cleaning to sanitize.

It’s ideal to always have wine in your barrels, but of course, this isn’t always possible. The best way to store barrels, which both avoids microbial contamination and drying out, is to fill barrels with water that’s been acidified with citric acid and 200 ppm of SO2. The water should be acidified to wine pH (at least below 4), so that the SO2 is effective — at higher pHs it offers little to no protection as it is useless at standard water pH levels. Top the barrel regularly and add 25 ppm SO2 every few months to maintain an effective SO2 level.

The most common way to store barrels is by burning a sulfur stick or ring in the empty barrel every month. Sulfur sticks are cheap and the burner apparatus can be purchased for around $40. Be sure to do this outside or in a well-ventilated area, as the smoke is horrific. It’s commonly suggested to leave a little water in stored barrels to keep them hydrated, but this little bit of water can lead to microbial spoilage growth and is not advisable. After storage with sulfur smoke, rinse barrels a few times and three-stage clean before putting wine in them.

After storing barrels dry, they will need to be rehydrated, which you can do with a steamer, or simply by using hot water. A trick to know if your barrel is sealed is to add hot water, bung tightly, then let the barrel cool for 10 or 15 minutes. When you remove the bung, if you feel or hear a vacuum, the barrel seals. If a vacuum has not been created, there is air entering the barrel somewhere, and you should repeat the hot water treatment.

Always smell the inside of your barrels (except when the last thing in them was sulfur smoke or an SO2 solution!) and pay attention to the wine inside of them, keeping an eye (nose) out for Brettanomyces and other spoilage organisms. Ridding barrels of spoilage microbes, especially Brett, is complicated, if not impossible. Spoiled barrels may be the only time it makes sense to stop using a barrel.

There’s a lot more that goes into making, using, and maintaining barrels than other vessels such as stainless; however, they offer more ways to impact a wine than less complicated options. They can be used to enhance wine structure, correct deficiencies, and add aromas and complexity — and of course they also look really cool in your home winery. It’s no wonder that they’ve become so entrenched in winemaking, despite their relative youth in the history of wine.

SOURCES

Jackson, Ronald S., Wine Science, Fourth Edition, 2014. Academic Press, Elsevier, Inc., London, UK

McGovern, Patrick. E, Ancient Wine 2019. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA

Smith, Clark, Postmodern Winemaking, 2014. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California.

Younger, William, Gods, Men and Wine, 1966. The Wine and Food Society Limited, London, UK