The Joys of Blending

Blending different grape varieties to make a better finished wine is a bedrock practice in the commercial wine world — and one often overlooked by home winemakers. If they do it in Bordeaux and the Rhone and Chianti, why not do it in your garage?

There are good and bad reasons to try blending, and it’s important to keep them straight. The real power of blending lies in the potential for adding complexity to the resulting wine — multiple flavors and aromas, something to stimulate every part of your mouth, a wine that has plenty of fruit at the start and something left for the finish. That’s why the winemakers in Chateauneuf-du-Pape in the southern Rhone are happy to have 13 grapes to work with, permitted by the appellation rules. Blending plays a large part in how they have made wines of great distinction for hundreds of years.

The second strength of blending is the pursuit of balance — that happy marriage of fruit, acid, tannin, alcohol, color and (sometimes) oak that makes great wines sing, and not-so-great wines seem full of wrong notes and missed opportunities. That’s the reason winemakers in Bordeaux temper the aggressive sharpness of Sauvignon Blanc with the fat, oily richness of Sémillon to produce memorable white blends.

Certainly there are grapes that stand on their own as single varietals, and there is no reason to mess with a good thing. But more often than not, the key is great fruit — the right vines, in the right climate, harvested at the perfect moment. The quality of fruit is one place where home winemakers are sometimes at a disadvantage, with little control over grape sources, modest equipment, and no budget for experimenting with, say, three types of French oak barrels.

This often leaves home winemakers, even very good ones, with batches of wine that are well-made but still a little thin, or a little too acidic, or just simple and one-dimensional. (Sound familiar?) This is where blending comes into the picture, helping create a whole that can be tastier than the sum of the parts.

Before getting to the mechanics, a warning about blending for all the wrong reasons. Blending is not a way to cover up faults in wine. Combining 5 gallons (19 L) of a wine that reeks of hydrogen sulfide or Brettanomyces with 5 gallons (19 L) of good wine just spreads the problem to an entire batch. A good rule of thumb: If you wouldn’t want to drink it, don’t blend it.

Deciding What To Blend

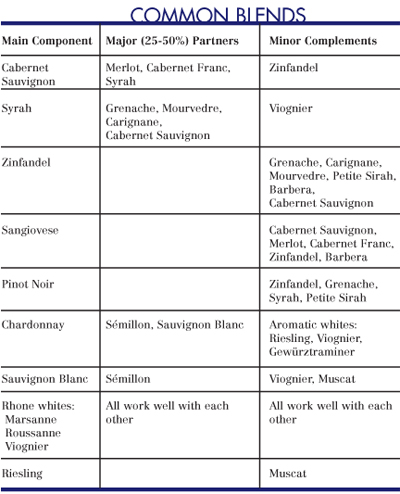

The possibilities for blending are endless — limited only by what grapes or wines you have. Most of the time, this means blending reds with reds and whites with whites, though even that seemingly obvious rule has its exceptions: traditional Chianti, for example, has always contained a splash of white Trebbiano. There are some classic combinations — Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot — but the fine print on labels at your local wine shop will reveal an amazing array of options.

Almost any grape wine can benefit from a pinch of something else. Some full-bodied, hearty varieties — Cabernet, Syrah — can hold their own with strong company. But others do not easily tolerate large additions, which can overwhelm that characteristics that make the varietal special. Pinot Noir, Zinfandel, Sangiovese and Riesling are in the latter category.

The final arbiter is your taste buds. One year a friend of mine had a batch of Nebbiolo that had never ripened properly; there was some charming cherry fruit, but it had the color of a rosé and the pucker of a lemon. We did trial blends with some Cabernet, then with some Syrah, and finally hit on a great match with 15% Syrah and 10% of an inky, low-acid Petite Sirah. It may have been a first, but it produced a fine, lively wine. There’s no penalty for creativity.

Finding Materials for Blending

If you have the space, time, equipment and confidence, you can do multiple small fermentations and then build up a blend to barrel volume. Having a half-dozen red wines to play with can be a great deal of fun, and highly educational.

But many home winemakers, especially while they’re getting the hang of it, just work with one variety of grape or a single wine kit. Which is precisely why the best source for blending material is other winemakers. If you have a Sangiovese and want to upgrade it to a “super-Tuscan,” you should be able to track down someone who works with Cabernet. If you want a new twist in this year’s barrel of Chardonnay, locate someone with a batch of Riesling.

Wine kits and concentrates are an excellent blending source; you can buy virtually any varietal at any time of the year. Mail-order fruit sources, particularly those that supply sterile juice and must year-round, are another great way to obtain small lots of blending grapes. And finally, if you’re dying to know what a pinch of Syrah would do for your Zinfandel, you can always blend in a couple of bottles of store-bought Syrah — it’s perfectly legal.

Blending Trials

The only way to know for sure if a blend makes sense is to try it — in a small, controlled blending trial. Over time you’ll devise your own protocols. But there are a few essentials:

1. Recruit several tasters; multiple palates are always better than one.

2. Take the time to talk about each component and blend along the way, identifying its aromas, flavors, tannin level and acidity. Don’t just rate it “good” or “bad.”

3. Keep careful track of the proportions in trial blends, and keep notes on what the tasters find in each — there’s bound to be too much information to keep in your head.

4. Have lots of clean, matching glassware on hand, as well as calibrated beakers and pipettes for precise and reproducible measurement.

One important question to ask beforehand is whether you are working on a familiar blend — this year’s variation on something you’ve done before — or something entirely new.

TRIED AND TRUE. Let’s say you have made a Bordeaux-style blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc for three years, and the ratio has worked out to roughly 60% Cabernet Sauvignon for body and structure, 25% Merlot to smooth the blend, and 15% Cabernet Franc for fruit complexity and aromatics. This year’s wrinkle is that the Cabernet Franc is coming from a new vineyard.

Start by providing your panel with samples of each component wine and spend some time describing and evaluating the characteristics of each. You may notice the Cabernet is riper and more voluptuous, the Merlot more tannic, and that this new Cabernet Franc has an intriguing, minty note on both the nose and palate.

Then try a “ballpark” blend made on the 60/25/15 model, alongside a sample of last year’s blend (which will obviously differ because of aging). Ask your panel if the new blend captures all the good things you found in the separate components, or do some of them get lost? And consider what makes this year’s blend different from last year — not just better or worse, but how it’s distinct.

Let’s say most of you think that the 60/25/15 blend is awfully tannic — the negative effect of this year’s Merlot? — and that the Cab Franc’s mint is hard to find. For comparison, try a new blend, 60/20/20. Chances are that a small percentage change will make a striking difference. Try 55/20/25 … and possibly discover the wine loses its structure. Continue with small incremental adjustments and experiments, and maybe come back to the project again the next day for a final judgment.

INTO THE UNKNOWN. For a blend that you’ve never made before, it’s probably best to impose more structure at the start. Let’s say you’re wondering whether a pinch of Riesling could liven up a clean but uninspiring Chardonnay. But who knows how much Riesling to add?

Start by tasting the wines separately and discussing their qualities. Then create a series of blends, perhaps in 5% increments: 80% Chardonnay and 20% Riesling, 85/15, 90/10, 95/5 and a reference sample with no Riesling at all. By tasting these blends, you can get a handle on the most promising range. If your tasters seem to like the 5% and 10% Riesling blends best, do another round with 1% increments — 5% Riesling, 6%, 7%…10%.

In most cases, objectivity is increased by tasting the various samples “blind,” using some system to code the glasses and only revealing the composition to the panel afterwards. For the same reason, if your panel is trying a series of graduated additions, mix up the order (5% Riesling, 20%, 0%, 15%, 10%). If you really want to level the playing field, have panel members taste the wines in different order.

Whatever you do, make sure to spit, and never underestimate palate fatigue — even the pros succumb to the buildup of acid and tannin sooner or later. That’s why a second pass another day, limited to the most promising options, is good insurance.

When to Blend

This question has lots of “right” answers. Many wineries in the Rhone, working with vineyards and styles that have been constant for generations, start blending in the fermentation tank. Most California wineries construct blends not long before bottling.

The winemaker’s knowledge of the wines is important. If you are working with blends that are old friends, starting early — let’s say, after a first racking, or when the wine goes to barrel — hastens the process of integration. But if you are not sure of your materials, waiting until the wines evolve and mature gives a much clearer picture of the final product. If the component wines are still changing individually, chances are the blend will keep changing, too, and need adjustment. White wine blends are best constructed after the separate batches have completed any planned processing — for example, malolactic fermentation or cold stabilization — since these treatments can significantly change the taste of a wine.

Two rules of thumb here might be: Blend as early in the process as you can, so the wines can get used to each other; but don’t blend unless and until you know what you’re blending.

Things To Watch Out For

Blending has its own set of traps and pitfalls. Even if a blend tastes promising, the biochemistry has suddenly changed. Blending places an extra premium on having accurate basic analysis results for your wines, whether you do them yourself or send samples out for professional testing.

A blend will have a different pH and acidity from any of the component wines, which means that the chemical makeup and stability has to be looked at again. Blending can be a great way to deal with excessively high or low pH or acidity, but a mixture of two high pH wines, however tasty, still has a problem. At a minimum, calculate the combined pH; better yet, test it and adjust accordingly. When you’re blending for color and flavor, watch your numbers.

Blending wines that have and have not gone through malolactic fermentation can create stability problems, restarting the malolactic in a carboy or, worse, in the bottle. Decide whether you want to encourage the malolactic to finish, or stop it. Either way, monitoring the SO2 level is important, and bottling should be postponed until you’re sure the wine is stable. Similarly, blending wines when one or more contains residual sugar can re-ignite yeast fermentations. Residual sugar blends may require sterile filtration or treatment with sorbate to suppress yeast. Leave enough time to be sure the wine is stable before bottling.

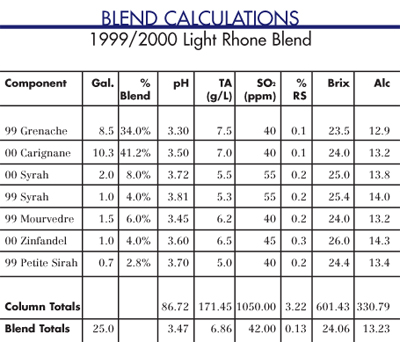

An easy way to track the consequences of blending is to use a spreadsheet, with formulas that do the math as you enter the numbers. It’s also a good way to do “what if?” blending — to see, for example, what would be needed to correct an acid or pH balance problem.

The template I use is at left. The formulas in the cells can be employed over and over; I just plug in the numbers for each potential component of any blend and let the spreadsheet run the numbers. This version was for a light, picnic-style Rhone blend that combined wines from the most recent harvest, leftovers from the previous year, and frozen grapes vinified a year after harvest.

The TA column contains total acidity in grams per liter; the SO2 column shows parts per million of free SO2; the RS column shows residual sugar as a percentage of volume. The values for pH, total acidity and residual sugar came from testing done at my local wine shop. The SO2 numbers reflected additions already made at the time the blend was calculated. Brix values were reported at harvest time.

Spreadsheet formulas do the rest of the work. Cells in the % Blend column simply divide the number of gallons for that component by the total gallons. The Alc values for each grape are created by multiplying the Brix figure (essentially the percentage of sugar in the grapes) by 0.55, which provides a rough alcohol percentage. The cells in the Column Totals row show the sum of the value in each row above multiplied by the number of gallons for that wine; the Blend Totals row simply divides the Column Totals values by the total number of gallons in the overall blend. If some of the values are out of date at blending time, I usually have the actual blend re-checked.

BLENDING TIPS FOR HYBRIDS

Wines made from hybrid grapes can be blended with very satisfactory results. But first you have to decide what you want to achieve. Are you trying to improve the color? Accent the fruit character? Increase the complexity? There are many reasons for blending. Some reasons are good and some are not so good.

I like to make a blended red wine from various French hybrids. A combination of Foch, DeChaunac, Chancellor and Chambourcin makes a medium-body red wine with good color and fruity characteristics. Chancellor should be used as the base wine, then blend to taste. These hybrids are compatible with one another, but some red hybrids are not. For example, you should not blend Leon Millot with Chambourcin. Taste and aroma are lost. Another problem hybrid is Baco Noir. It has deep color initially, but the color becomes unstable as it ages.

Can you blend a white hybrid with a red hybrid? Sure! Try blending DeChaunac with Vidal for a light rosé style of wine. Other white hybrid wines that are compatible are Vidal, Seyval and Cayuga. Use Vidal as the base wine with different proportions of either Seyval or Cayuga or both. Blending these three varietals in different percentages will give you complexity, taste, aroma and sometimes color (a light straw color).

Traminette, once known as the “Gewürztraminer hybrid,” blends well with Cayuga and Vidal. It should be used as the base wine. Traminette and the Gewürztraminer vinifera are also compatible blending partners. — Don Gauntner

BLENDING TIPS FOR FRUIT WINES

Blending fruit wine can be a challenge, because you want to maintain the taste and aroma of the varietal fruit. Cherry wine should taste and smell like Mom’s cherry pie! Peach wine should taste like peaches and raspberry wine should taste like raspberries. With this rule in mind, I often blend different varieties of the same fruit. For example, when making apple wine, in order to achieve a balance of sweetness, tartness and fruity aroma, I might blend high-acid apples (like Winesap) with aromatic apples (like MacIntosh) and sweeter apples (like Red Delicious).

You can blend different fruit wines for complexity, but the varietal aroma and taste may be lost. Blending nectarine wine and peach wine will add complexity without the loss of peach flavor and may improve the color toward a deeper tint of pink.

Black raspberry and red raspberry are compatible blending partners. A small percentage of black raspberry has color stability and will enhance the color of red raspberry wine. Strawberry wine tends to be yellow or orange in color and can be improved with a small-percentage blend of black raspberry. Caution: Too much will affect the strawberry flavor. Red raspberry and cherry also are compatible wines for blending.

Think carefully before you blend other berry fruit and stone fruit wines. Decide what you want in the finished wine. Is it a better fruit wine as a varietal or a blend? If the answer is the latter, don’t be afraid to experiment! — Don Gauntner

Final Thoughts

Blending can be a last resort, but also the route to more interesting wines. Either way, home winemakers can improve their skills and broaden their cellar. If that’s not enough, blended wines — especially novel or complex ones — have a good chance of catching the attention of judges. The wine in the spreadsheet, I’m happy to report, took gold at my county fair!