“In victory, you deserve Champagne, in defeat, you need it.”

“In victory, you deserve Champagne, in defeat, you need it.”

— Napoleon Bonaparte

Champagne was not only made popular by such great quotes, but also by celebrity endorsements or excesses. It’s no secret that James Bond (Agent 007) had a strong penchant for Bollinger Champagne and it has been reported that Marilyn Monroe once filled her bathtub with 350 bottles of Champagne and took a long, luxurious bath in it.

Champagne, the dry sparkling wine (a.k.a. bubbly) from the northeastern French region bearing the same name, has long been considered the ultimate beverage of choice when celebrating a special occasion.

But gone are the days when sparkling wine was only drunk to mark a special occasion or to pair with luxurious delicacies such as caviar. Sparkling wine makes an excellent aperitif on its own or with simple hors d’oeuvres, seafood entrées or sushi, or it can be enjoyed with dessert if the wine is off-dry or sweet.

There are sparkling wines available now for every price point. Some of the finest bubblies of the world are now produced inexpensively from New World winemaking regions and other Old World regions such as Italy, Spain and Eastern European countries.

And, as wineries try demystifying table wines by simplifying labels — first and foremost by identifying grape varieties as opposed to strictly provenance — sparkling wine marketers are also working hard to make bubbly more consumer and food friendly, something that can be enjoyed any day.

This guide is meant to further demystify sparkling wines. It will help you understand the different sparkling wine production methods, including what options are available to home winemakers, and how they influence the style of wine.

NOT ALL BUBBLY IS CHAMPAGNE

Champagne’s popularity has made the name synonymous with sparkling wine, but not all sparkling wine is Champagne. Only sparkling wine produced from specific Champagne regions, for example, Reims and Épernay, produced by the traditional method using only Chardonnay, Pinot Noir or Pinot Meunier grapes can be labeled as Champagne.

(There are other production criteria, however, these are the major ones.) Other sparkling wines from France, but outside of Champagne, produced using the traditional method are referred to as Crémant, while in Spain they are known as Cava.

The traditional method, most often referred to as méthode Champenoise or méthode traditionelle, requires that bubbles be produced naturally within each bottle by a second fermentation, known as prise de mousse, which is initiated through the addition of a liqueur de tirage, a mixture of sugar and yeast, to a still wine.

The still wine is referred to as the base wine, or cuvée, and it consists of a blend of many different wines carefully blended by the cellarmaster, or chef de cave. The cuvée can often be a blend of hundreds of different wines. If all component wines are from a single vintage, the final sparkling wine is vintage dated.

Wineries that choose to make a consistent style year after year will blend wines from two or more vintages to produce a non-vintage, or multi-vintage, sparkling wine.

During bottle fermentation, yeast consumes sugar to convert it into alcohol and carbon dioxide (CO2) gas; the gas remains trapped inside the bottle, dissolved in the wine. The pressure inside the bottle can reach up to 6 bars, approximately 90 pounds per square inch (PSI) — the equivalent of three times the pressure in car tires.

The wine is allowed to ferment and mature for several weeks at cool temperatures, between 50 and 54 °F (10–12 °C), with bottles in the horizontal position, or sur latte. This extended contact with the spent yeast cells from fermentation is what gives sparkling wine its yeasty, nutty aromas and complex flavors.

It can last a few weeks to several years depending on the desired flavor profile — and cellarmaster’s patience. Following the long sojourn in bottle, the dead yeast cells are allowed to drop and collect in a special crown cap closure, known as the bidule, through a labor-intensive method known as riddling.

Riddling, or remuage, is the process of twisting, turning and tilting bottles from a horizontal to a quasi-vertical position on a riddling rack, or pupitre, to allow the spent yeast cells to collect in the bidule, a process that takes approximately three weeks. The cellarmaster may choose to further age the sparkling wine by transferring bottles in their vertical position, or sur pointe, to a holding container.

When the wine has reached its desired flavor profile, the cellarmaster removes the spent yeast from each bottle by a process known as disgorging, or dégorgement. The bottle is held vertically, pointing down, and with a disgorging key, the crown cap and bidule are removed whilst the bottle is brought to a horizontal position.

This allows the sediment to fly out of the neck of the bottle leaving the wine crystal clear, if done properly. Often the process is made more effective by first freezing the neck of the bottle in a brine solution to freeze the sediments.

The last critical step, the dosage, involves adding a small volume of cuvée to which a little sugar is added to balance the wine’s acidity and to achieve the desired style, from bone dry to sweet. The French refer to this cuvée solution as the liqueur d’expédition, and often contains a distilled spirit such as Cognac.

Champagne is a cool-climate grape growing area and, as such, grapes do not reach high sugar levels as in warmer climates and have higher acidity, hence the need to balance with sugar.

The lower sugar level yields a base wine with typically 10.0 to 11.0% alcohol by volume (ABV). Bottle fermentation adds another 1.5% for a total of 11.5 to 12.5% ABV for the finished wine. The final step involves inserting a cork partway in the bottle and securing it with a wire cage.

(The partial insertion is what gives the cork its distinctive mushroom shape once removed)

Most sparkling wines are ready to drink once finished and can last up to two or three years in the bottle; however, the best bubblies of the world, namely those produced in the traditional method, can live many more years with appropriate cellaring.

This laborious process and long aging period explains the high price of sparkling wines produced in the traditional method.

OTHER BUBBLIES

The quality of sparkling wine is judged by aroma and flavor complexity and size of bubbles; the smaller the bubbles, the higher the quality. Bottle fermentation, as in the traditional method, yields the smallest bubbles; however, such sparkling wine is labor-intensive and costly to produce.

The most common and cost-effective alternative to the traditional method is the Charmat or Cuve Close (sealed tank) method, which is used to produce many of the world’s inexpensive but good-quality bubblies.

Bubblies produced with patience and care using this method can rival some of the great Champagnes although the method is commonly used for rapid commercialization of cheaper sparklings. Bubbles in these are markedly bigger and aromas and flavors are not as intense, but they provide excellent value. Flavor intensity and complexity, and quality in general, can be improved through longer aging of the wine on the lees.

Asti Spumante, the famous low-alcohol (approximately 8% ABV) sweet sparkling wine from Piedmont (Italy), Germany’s Sekt, and Ontario’s sparkling Icewine are examples of sparkling wines produced using the Charmat method or a variant.

The Charmat method consists in conducting the second fermentation in bulk in pressurized, sealed stainless steel tanks, and bypasses the need for bottle fermentation, riddling and disgorgement. The wine is then refrigerated to stop fermentation, filtered, a dosage is added and then bottled under pressure so as not to lose any precious carbon dioxide gas.

A less common method of making sparkling wine has gained great popularity in Russia and Ukraine. A variant of the Charmat process, the Russian or continuous method uses a series (e.g. 5) of pressurized tanks linked sequentially.

The first tank contains the cuvée and tirage (sugar and yeast solution). As fermentation starts, wine is channeled through the second and third tanks each containing wood shavings. Wine is then channeled through the fourth and fifth tanks where it clarifies prior to being bottled.

Although wine is in contact with the lees for a longer period than in the Charmat method, the continuous method usually takes less than a month and therefore yields wine of inferior quality.

Another less common method is the transfer or racking method whereby wine fermented in the bottle is transferred under refrigeration to a bulk transfer tank. Dosage is added and the wine is then bottled under pressure.

MAKING BUBBLY AT HOME

Fortunately for home winemakers, there are several alternatives to making good-quality sparkling wine in addition to the traditional method: using a sparkling wine kit, by carbonation or using the dialysis method.

Sparkling wine kits using concentrate are now available and contain everything necessary to make a very good bubbly. These kits use a variation of the méthode Champenoise; they still ferment in the bottle but the sediment is not disgorged.

Dosage is added but the wine must be allowed to rest again to allow dead yeast cells to precipitate again. The final wine requires careful pouring from the bottle so as not to disturb the sediments at the bottom.

The more common method uses carbonation equipment to inject and dissolve carbon dioxide gas in the wine, a process similarly used in soft-drink production. This method produces very good sparkling wines, commonly referred to as crackling wines, with much less effort and risk although bubbles are considerably larger and fade faster compared to premium sparkling wines.

A common method uses a counter-pressure bottler; a specialized piece of equipment that injects CO2 gas into wine under pressure. This method is described in the story, “Carbonate Bubbly,” in the Techniques column on page 64. Another alternative uses a carbonating stone made of ceramic or sintered stainless steel with miniscule holes that inject tiny bubbles into the wine from a CO2 tank.

The advantage of carbonated over bottle or bulk-fermented sparkling wine is that if you have a still wine that you want to turn into a bubbly, it can be easily done without increasing its alcohol content.

If you still prefer making sparkling wine using the traditional method, but hate the thought of having to riddle and disgorge, the dialysis method may be your best alternative. The method involves placing the yeast inoculum in dialysis tubing and inserting it in the bottle containing sweetened wine to initiate bottle fermentation.

The tubing has microscopic pores that allow the sweetened wine to interact with the yeast through the pores and ferment, but the larger spent lees particles are restricted inside the tubing. At the end of fermentation and aging, each bottle is uncapped and the tubing with spent lees is retrieved, leaving the wine crystal clear.

No riddling, no neck freezing, no disgorging required! The greatest advantage of the dialysis tubing method is that you only make as many bottles as you desire. For detailed instructions, please refer to “Sparkling Wine, M.D.” in the June-July 2004 issue of WineMaker.

STYLES OF BUBBLY

The most popular choices of grape varieties in France for sparkling wine are Chardonnay, Pinot Noir or Pinot Meunier, or a blend of any of these. Other popular varieties include Chenin Blanc, Muscat and Riesling for whites, and Syrah (Shiraz) for reds.

Rosé sparkling wine is usually made from red grapes using a very short maceration period to extract a little red color, although a small percentage of red wine can be added to a white sparkling wine to achieve a desired color, albeit with a very different flavor profile.

A white sparkling wine made strictly from a white grape variety, such as Chardonnay, is known as a blanc de blancs whereas a white sparkling wine from a red grape variety, such as Pinot Noir, is known as a blanc de noirs.

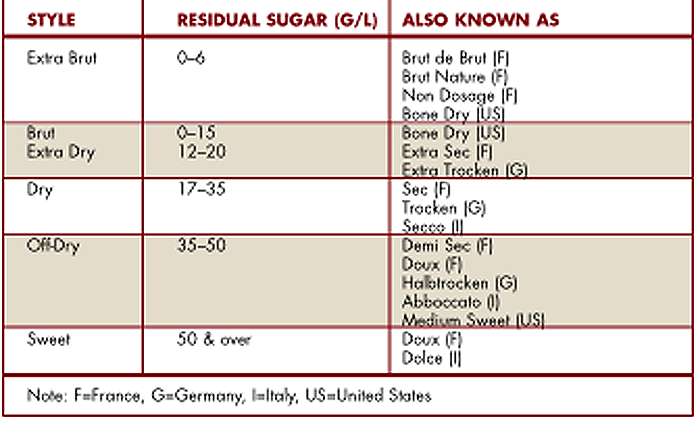

Other than color, sparkling wines are most often classified according to the amount of residual sugar or relative dryness. For example, a Brut sparkling wine can have up to 15 g/L of residual sugar.

Countries have different designations and requirements relative to residual sugar content. (The table at right provides guidelines for many common styles.)

APPRECIATING BUBBLY

The sparkling wine production methods described earlier should help you decide what method best suits your skills, patience and budget for making bubbly at home. In any case, know that you can enjoy bubbly any day of the week, and experiment with different food pairings.

If you don’t, you could end up like John Maynard Keynes, one the most important figures in the history of economics, who once said, “My only regret in life is that I did not drink more Champagne.”