Country wine is the informal term that has been used for years to define fermented beverages made from ingredients other than grapes. This can include fruits, vegetables, flowers and herbs. Wine made with honey is called mead and wine from apples is cider (5 to 7% alcohol).

Every home winemaker should make room in his or her cellar for country wines. They taste fresh and fruity; they reflect the aroma and flavor of ripe fruit. They are inexpensive to make. They are refreshing to drink when the acids are balanced with the other wine components (alcohol, tannin and residual sugars). While most of your grape wines age, country wines can be the “drink now” beverages in your cellar. Country wines can be made in a dry, semi-dry, semi-sweet or sweet styles. A variety of fruits can be fermented separately and blended to make lively libations. There is something to be made for everyone’s palate!

Wines made from fruits such as berries, peaches, pears, apples, rhubarb, tomatoes, watermelon, rosehip and dandelion benefit from the winemaker’s decision to control the acids, sugars, nutrients, vitamins and tannin content, as well as the yeast strain, to maximize the fruit flavors.

As a general rule of thumb, country wines have a limited shelf life while most grape wines benefit from at least a bit of aging. Country wines are typically consumed while young, within three months to two years (with a few exceptions, like elderberry) and do not generally improve with bottle aging. The fruit flavor loses its freshness and the color fades. To maximize enjoyment from each of these wines, make sure you test and adjust the acidity and free sulfite levels before bottling.

Most berries are high in acids. The easiest way to control the acids in berries and fruits for winemaking is amelioration (adding water) or limiting the quantity of berries or fruit to the volume of water used per gallon. This is the balancing act for the winemaker. While you want plenty of flavor, you do not want so much tartness that you pucker when you sip! Since acid is the backbone of a wine, titrate the acidity of the must (juice) before fermentation and, again, in the wine before bottling.

The acid range for dry fruit wines will be 0.55 to 0.65 percent. This is, of course, a generalization since there are many memorable fruit wines with acid levels of 0.70 to 0.80 percent. These wines are usually sweetened before bottling to balance the taste of higher acids. Remember: If the must (juice) does not have enough acidity during fermentation it can be too slow or may stop fermenting. The resulting wine may also have a medicinal taste. If higher acid levels are desired, consider balancing the acids with sugar after fermentation.

Other country wines — such as banana, dandelion, mead, melon, watermelon, persimmon, pear and tomato — need acid additions to make a wine balanced. The use of a commercial acid blend provides a balance of acids to make a pleasant wine. Old fashioned recipes used oranges and lemons to provide citric acid. These recipes may still be used as long as the citrus peel is not added. The oils in the rinds can actually inhibit a healthy fermentation. The use of a complete yeast nutrient is strongly suggested in all country wines since these fruits and flowers lack sufficient nitrogen, trace minerals and vitamins that are essential for healthy yeast metabolic activity.

All fruits can vary in juice content. Geographical and weather conditions may also contribute to the overall liquid content of the fruit. Fruits benefit from the use of pectic enzymes to release the juice from the fruit before and during pressing. These enzymes need 1–4 hours or overnight contact to break down the pectin in the fruit. Treated juices settle better and filter more easily than untreated juices. Use fresh pectic enzymes and mark the label with a date as it loses strength during storage. In addition to the regular pectic enzymes there are two newer products for fruits. Pearex Adex is a pectic enzyme formulated for pears, apples and quince and other light colored fruits. Adex-G2 may be used for acidic dark fruits such as raspberries, blackberries, currants, blueberries and native American grapes, such as Concord. Follow recommended dosage for fruits.

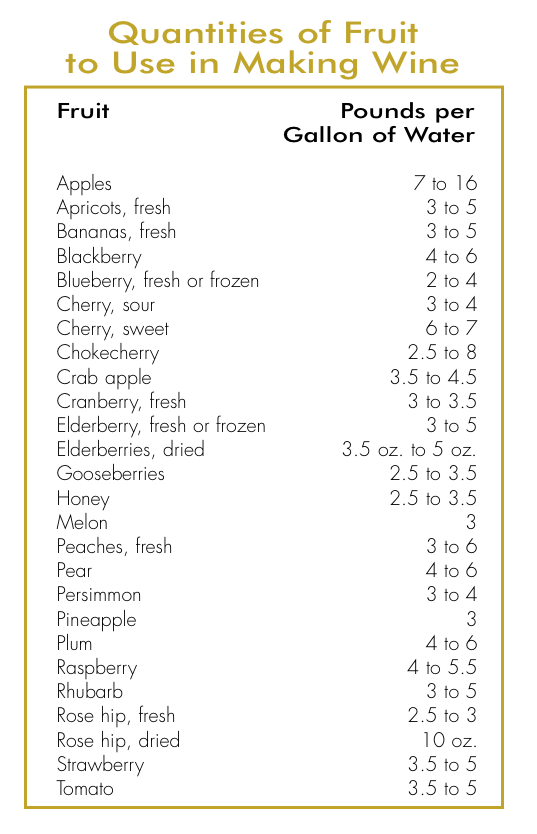

How much fruit does it take to make a gallon of wine? For guidelines, see the table at lower right. You can use more or less fruit than the recommended quantities. However, less fruit usually means less flavorful wine. More fruit per gallon of water will, in most cases, increase acidity and may make the wine too tart to be pleasurable.

Test the acidity of the must, using an acid test kit. Be sure to follow the guidelines for fruit wines. If using an acid test kit seems intimidating to you, ask your wine hobby supply store for help. They can show you how to do the test. Remember, the hydrometer and acid test kit are to the winemaker as a compass is to a mariner. They show winemakers where they have been and where they are going.

Skill is required to make a good fruit wine. The three cardinal rules for working with fruits are the same as for grapes:

1. Always use ripe, unblemished fruit. You cannot make an excellent wine if you do not start with excellent fruit.

2. Always be clean! Sanitize all equipment before and after use.

3. Always use sulfites to stabilize the fruit and wine to prevent bacterial activity as well as oxidation.

Juice Versus Pulp

Preparing the fruit for fermentation is important. Some fruits are soft and are easily mashed or crushed to produce juice. Hard fruits, like apples and pears, need to be cut and pressed to release their juice. Firm berries, like dried elderberries, can be softened by adding boiling water. Freezing berry fruits can also release more juice. Stone fruits such as peaches, plums and apricots are fermented on the pulp and benefit from the use of pectic enzyme to break down the cell walls of the fruit to release the juice. Dried fruits can be minced and then treated with warm water to release the sugars and flavors. Citrus fruits, like oranges and lemons, use only the juice; the peels are never used because the oils are bitter tasting and can inhibit fermentation. Rhubarb is cut and sugared to release the juices. Flower wines should be made with only the petals; no stems, no greens.

Note: Some fruits can be prepared by more than one of the methods mentioned above. Work with the fruit as soon as it is picked or purchased to ensure a quality wine. Remember, superior wines are made using superior quality fruit!

Reasons to Blend Fruit Wines

1. To Achieve Acid Balance: Most fruit wines should have acid levels that are 0.55–0.65% total acidity. Some fruits contain high citric and malic acid. Combining a high-acid fruit wine with a low-acid wine can bring balance and more enjoyable flavors.

2. To Maintain or Add Color: Some country wines tend to brown easily. Blending different wines, concentrated fruit juices or red wine coloring agents can enhance your visual enjoyment and a wine’s color stability.

3. To Stretch the Crop Size: Sometimes we do not have enough of one fruit to make a batch of wine. Maybe the crop is small or the market is short of quality fruit. Combining several types of fruit is a practical answer.

Country Wine Case Study: Making Raspberry Wine

Ingredients

5.0 lbs. (2.3 kg) fully ripened or frozen raspberries placed in a fine mesh straining bag

7 pints (3.3 L) water

2.0 lbs. (0.91 kg) corn sugar or table sugar (Before adding the sugar, use a sugar scale hydrometer to determine the level of sugar in the must. Adjust sugar addition to match the desired potential alcohol level.)

1/2 tsp. acid blend (Before adding acid blend, use an acid test kit to determine if an acid addition is necessary — target acidity should be 0.65 to 0.80).

10 drops liquid pectic enzyme (or, if using dry pectic enzyme follow manufacturer’s directions)

1 tsp. yeast nutrient with energizer

1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved

After 24 hours, add: 1 package wine yeast (Red Star Côte des Blancs, Premier Cuvée, Pasteur Champagne, Lalvin K1V-1116, or EC-1118, Fermiblanc or R2)

After fermentation is complete add: 1 Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved fining agent, per package instructions.

One month to six weeks after fermentation is complete, or when racking after fining add: 1 crushed and dissolved Campden tablet.

Step-by-step

1. Pick your raspberries when they are fully ripe. Remove all stems, leaves and foreign matter. Cut and discard any rotten fruit. Wash and drain the berries. To contain pulp and tiny seeds, place fruit in a fine mesh nylon straining bag. If frozen fruit is used, thaw. Lightly mash fresh fruit. Place juice into 2–2.5-gallon (7.6–9.4 L) primary fermenter. To keep all of the pulp in the straining bag, tie the top of the bag. Place the fruit filled bag in the primary fermenter. Fruit should be submerged.

2. Combine water and sugar in a sauce pot and heat to dissolve the sugar. Cool. Pour the sugar solution into primary fermenter. Hydrometer reading will be 21–22 °Brix. Take an acid reading using an acid test kit. Adjust acid levels to 0.65–0.8 (remember, 1 teaspoon of acid blend per gallon (3.8 L) will increase the acid level by approximately 0.15).

3. Stir in acid blend (if needed), pectic enzyme and yeast nutrient and Campden tablet. Cover primary fermenter and let sit 24 hours. In the meantime, make a yeast starter to expand the yeast colony. Yeast starter recipe: Bring to boil 1 cup orange juice and 2 tablespoons sugar. Let solution cool to 70–80 °F (21–27 °C). Stir in 1/2 teaspoon complete yeast nutrient. To rehydrate yeast, measure 1/4 cup warm water (100–105 °F/37–40 °C), then sprinkle yeast on top. Let yeast sit for 5 to 10 minutes. Stir to dissolve.

4. Add the yeast starter to the cooled orange juice solution. Sanitize a 750 mL wine bottle or pint-size jar. Pour orange juice and yeast solution into clean bottle. Cover with a clean cloth or fit bottle with an air lock and #2 drilled rubber stopper. Yeast starter will be ready in 12 to 24 hours. Stir the yeast into the must (juice). Cover. Stir the must vigorously twice daily. After three days or when hydrometer reading is 8 °Brix (specific gravity 1.030), lightly press juice from bag and transfer to the secondary fermenter. Siphon the remaining wine from the primary container into a glass secondary fermenter. Attach a fermentation lock half filled with water. Discard pulp and clean straining bag.

5. When fermentation is complete (-1.5–0 °Brix (specific gravity 0.994 to 1.000), rack off the sediment into another clean and sterile glass carboy. Stabilize the wine by adding one Campden tablet, crushed and dissolved in a small amount of warm water. Once fermentation is complete, add the fining (clearing) agent according to manufacturer’s directions. Let sit 2–3 weeks and siphon the wine away from the sediment. Discard the sediment.

6. Let sit 6 weeks and rack again. Rack a third time after another 6 weeks have elapsed. When clear and stable, taste the wine. Adjust the sweetness of the wine to suit your preference. If a dry wine is preferred, check the sulfite level and adjust to 35–45 ppm free sulfite, filter, and bottle. To make a sweet wine dissolve 1/2 teaspoon potassium sorbate in a small amount of water. Add to the wine and stir thoroughly.

7. Then perform sugar bench trials to determine the level of sweetness that best enhances the fruit. Compare the aromas, flavors, acid balance, and aftertaste. Taste and determine the residual sugar level that best accents the wine. Do the necessary math by multiplying the amount of sugar needed for the volume of wine to be bottled. Stir thoroughly. Check the sulfite levels, adjust if necessary and filter the wine for a brilliant appearance. Siphon wine in clean, sanitized bottles. Enjoy!