Wine and grape juice is a naturally acidic solution. A pH reading has an inverse relationship with acidity, in that, the lower the pH measure, the higher the acidity. While a wine’s total acidity (TA) can tell you a lot about the beverage in front of you, there is another measure that can indicate how powerful all that acid is. This measure is pH and professional winemakers consider it the life line of a wine. A wine’s pH will affect its flavor, aroma, appearance, color and aging capability. In this article, we talk to three professional winemakers about the role pH plays in their winemaking and how you can work with it at home.

Steve DiFrancesco is Winemaker for Knapp Winery in the Finger Lakes of New York. Steve is enjoying his 28th harvest this year. He began his career in the late 1970s making sparkling wines at Gold Seal Vineyards also of the Finger Lakes. He has also worked at Bully Hill Vineyards and Lucas Vineyards (both of the Finger Lakes). He enjoys working with varietals such as Riesling, Sangiovese and Muscat.

A lower pH wine has a livelier mouthfeel, has brighter color and is more biologically and chemically stable. A pH that is too high will have a soapy mouthfeel. If the pH is too low, the

acid is probably high, or the grapes were unripe, and those issues will be noticeable.

Wine pH typically ranges between 3.1 and 3.6, and most inexpensive pH measuring methods are not accurate in that range. pH meters work better if they are run often, as well. I would recommend sending samples out to a lab that runs pHs often.

The pH of the wine will increase by lowering the acid, through malolactic fermentation, or additions of potassium bicarbonate or calcium carbonate. Cold stabilization reduces TA, however, potassium contributes to a higher pH, and when it precipitates during cold stabilization, it lowers the pH. This only happens at a pH of approximately 3.65 or lower because of the relative concentrations of tartrate and potassium in the wine. At a pH of greater than 3.65, cold stabilization actually raises the pH.

To lower the pH of the wine, tartaric acid additions to a low acid wine will lower the pH both by raising the acidity and through the release of the hydrogen ion through tartrate stabilization, as mentioned before. Malic

or citric acid additions can encourage biological problems, and are usually counterproductive.

Michael Martini is Winemaker at Louis M. Martini Winery in St. Helena, California. He is a graduate of the winemaking program at UC-Davis and worked alongside his father Louis P. Martini (son of winery founder Louis M. Martini) before taking the reins as Winemaker in 1977.

pH is the life of a wine. It gives it sharpness or crispness to keep it from getting flabby or cloying. This usually means brighter fruit in the nose and pallet and less perception of tannin (to a point). As far as measuring pH, there are actually very cheap pH meters on the market. In substitute but at the loss of a lot of accuracy you can also get pH strips from your local drug store or winemaking supply shop.

Wine with too high a pH will taste flabby and dull. Also the color in reds has a tendency to become more purple than red when the pH level is too high. When the pH is too low, the wine will usually bite your tongue off. It is very obviously perceived as overly acidic.

To increase your pH, you can take two routes. The first is to decrease the acid, which can be accomplished by plastering, i.e. adding a basic salt (such as calcium carbonate) that will precipitate acid. The second is to put a touch of sugar into the wine in order to mask it.

To decrease the pH, one must only add acid — tartaric is the most commonly used, however you can use citric (which may be easier to get a hold of but isn’t as stable in the wine). The biggest thing is to always do an experiment on a small lot of your wine to see if it works before potentially messing up the whole batch!

Ondine Chattan has been the Assistant Winemaker at Geyser Peak Winery in Geyserville, California since 1999. She has a graduate degree in oenology from Fresno State University in California. Ondine began her wine career at Cline Cellars and has also worked at Ridge Vineyards, both located in Sonoma County, California.

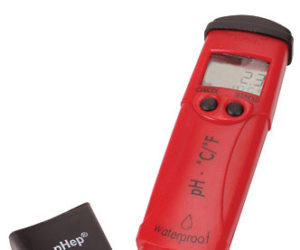

Brilliance of color is often a good pH indicator as high pH wines tend to have a dull purple-blue hue, while very low pH wines have an unnatural cherry-red hue. For home winemakers who make a barrel or more it would be worthwhile to invest in an inexpensive portable pH meter. If you take the time to maintain such a meter, it will last many vintages and a fine one can be purchased for about $50. I am not as enthusiastic about the pH test strip papers, as the color of the wine can influence results. That said, they are still better than using nothing at all.

High pH wines are dull and do not age well as they tend to lose their vibrancy and fade quickly. From the early stages of fermentation, high pH wines show a dullness of color and feel broad and lackluster on the palate. It is far rarer to see low pH in California, but an astringent, bracing acidity is frequently associated with excessively low pH wines. Keep in mind that taste is a difficult indicator during fermentation, as sugar will mask acidity and provide texture.

The simplest solution, of course, is blending a high or low pH wine with a more balanced wine, but it is better to avoid getting into the situation. Beware of excessive hang-time in the vineyard!

Too high of a pH can be a difficult predicament to resolve and has far-reaching implications. Acid additions do not always rectify a too-high pH and can make a wine angular and disjointed. Because of this, it is best to not let the pH get away from you. Measured tartaric acid additions appropriately timed during fermentation (after soak-out and again a few days later) will incorporate well into the wine and prevent any really bad microbes from gaining a foothold in the wine. As for too low pH it is possible to drop-out excessive acid by using potassium carbonate or calcium carbonate. This should be done early in the wine’s life and long before bottling to ensure that no significant precipitation takes place in

the bottle.