Upgrade Your Home Winery

If you are like most home winemakers, you’ve been making great wines from concentrate and juice, and you also may have experimented with small batches of grapes. Now you want to increase your production. Or you want to try different styles of wine and master some sophisticated techniques. Or perhaps your love for winemaking is driving you to become a garagiste — a home winemaker who converts the garage into a “winery” and is obsessed with making the best wines possible.

So how do you upgrade your starter kit — your five-gallon pail, glass carboy, hydrometer and racking cane — to make better or different styles of wine, or to expand to an impressive amateur operation capable of handling 50, 100 or even 200 gallons of wine per year? (Before you get carried away, remember: In the United States, federal regulations limit homemade wine production to 100 gallons if one adult lives in the household and to 200 gallons for two or more adults.)

Whether you’re driven by quality, quantity or efficiency — or by the high-tech joy of using the latest home winemaking toy — this guide will help you decide what to buy. We’ll sift through the plethora of specialized winemaking equipment to find tools and gadgets that match your budget, annual wine production and goals.

Note: The U.S. prices listed in this article are approximate and were taken from the most recent 2002 catalogs of national home winemaking retailers and mail-order suppliers. Prices can vary significantly.

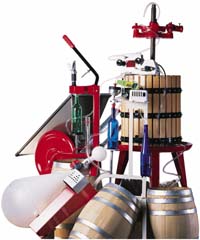

Crusher and Press

The major difference between winemaking from concentrate or juice and winemaking from fresh grapes is that the latter requires extracting juice by mechanical means, specifically crushing and pressing. In red winemaking, the crushed grapes also have to soak in the juice during fermentation — a process known as maceration — to extract color, tannins and other phenolic compounds that give wines their color, structure and flavors. The crusher and press should be the first items on your acquisition list if you are upgrading to winemaking from grapes.

The crusher is used to break the grape skins to expose the juice in preparation for maceration for red winemaking, or to ease pressing and juice extraction in white winemaking.

The most basic crusher, the manual crusher, consists of two aluminum fluted rollers, a hopper and a flywheel-crank assembly. It costs approximately $180. A motorized version that greatly simplifies crushing also is available. Crushers come in painted-steel or stainless-steel models. I recommend a model with a stainless steel hopper at a minimum (only the frame is painted), which will last a lifetime and will not contaminate the juice with rust.

An important drawback of the crusher is that stems are crushed and are not separated from the must — the mixture of juice and crushed grapes. Therefore, stems need to be removed manually, a tedious and messy task. Stems should ideally be removed to avoid imparting overly harsh tannins and herbaceous flavors to the wine. They also increase the wine’s pH, therefore affecting the chemical balance, which results in reduced color intensity, reduced aging potential and increased susceptibility to spoilage.

A crusher-destemmer (often called crusher-stemmer) is the solution. It first crushes grapes and then channels them through a perforated drum-like screen that allows grapes to drop into the fermenter, but expels stems out an exit chute for disposal. Both manual and motorized models are available; they cost approximately $450 and $600, respectively, or up to $1,000 and more for an all-stainless model.

The downside of the crusher-destemmer is that grapes and stems are first crushed, and then the stems are removed. Undoubtedly, stem crushing imparts some of the harsh tannins and herbaceous taste to the wine. I have found that the results are still very good in spite of this drawback. The ultimate solution is the destemmer-crusher, which first destems and then crushes. It is a bulky machine, really intended for small commercial wineries, with prices for the most basic model starting upwards of $4,000.

The wine press (often called a basket or vertical press) is used to apply pressure on crushed grapes to extract juice. In white winemaking, grapes are usually pressed immediately after crushing. In red winemaking, grapes are pressed at the end of maceration and fermentation.

Wine presses have evolved considerably from the ubiquitous basket press, still the most popular because it is efficient and well-priced. The basket press consists of a cylindrical hardwood basket to hold the crushed grapes and a ratchet mechanism and hardwood blocks for exerting pressure. Bladder and hydraulic presses, which use air/water pressure and hydraulic pistons, respectively, are very expensive (upwards of $2,000) and geared to commercial wineries.

For home winemaking, the basket press will perform well and last a lifetime. They are priced up to $500 depending on capacity. For example, a #45 basket press has a capacity of 700 pounds (318 kg) of grapes and costs between $400-500. The # on the popular Italian basket presses refers to the diameter of the basket in centimeters.

Estimate your annual production needs and choose an appropriate press. A press that is too small will require multiple pressings, and therefore more time and effort, while one that is too large will prevent the press assembly (wooden blocks) from reaching down to the grapes. If you have the option of single- or double-ratchet action, choose the latter; it moves the press assembly down on both the forward and backward motion.

Fermenters

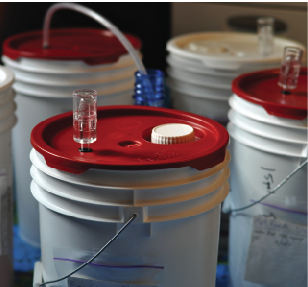

Fermenters come in many different materials, including food-grade plastic, glass, stainless steel and wood. Fermenters can be open or closed, and may also double as storage containers for bulk aging.

Large, open, food-grade plastic fermenters are very practical for home winemaking from grapes. The crusher-destemmer is simply rested on top of the fermenter to allow grapes to fall into it in preparation for maceration and fermentation of red wine. For example, a 90-gallon (350-liter) fermenter with an opening approximately the same length as the crusher-destemmer greatly simplifies crushing. There is no need to transfer the crushed grapes; simply place a cover, such as a tarpaulin, over the fermenter to protect the juice from fruit flies and the elements. Carbon dioxide gas produced during fermentation will protect the wine from spoilage.

A favorite amongst home winemakers are 60-gallon (240-liter) plastic drums used for storing apple juice that can be bought for under $20. The only inconvenience is their small opening at the top which does not accommodate the crusher-destemmer. The basic crusher (without destemmer) will fit nicely. A catch stand ($150-300) that acts as a funnel or chute can be used to transfer crushed grapes from a small container to the plastic drum.

Glass carboys and demijohns remain the most popular types of closed fermenters in home winemaking, and cost between $15 and $50 depending on volume. They are usually used for fermenting white wine as well as storing and aging any kind of wine. They are not used in the initial fermentation phase in red winemaking from grapes because it would be impractical, if not impossible, to transfer crushed grapes through the neck of glass containers.

Stainless-steel fermenters are gaining popularity because of their affordability, accessibility and multi-functionality. They are very easy to clean and maintain, and are completely inert, which means that wine does not react with the stainless steel. You can use these tanks for fermentation; they also are ideal for aging and bulk storage of large volumes of wine.

There is an amazing selection of tank types with countless features to fit anyone’s budget, space constraints and production. All tank types are either of variable capacity or fixed volume.

A variable capacity tank consists of an open top, a fixed volume tank and a floating lid. The lid is equipped with an airlock and an inflatable gasket around its circumference, which can be used to protect any volume of wine in the tank. A racking valve at the bottom of the tank is used for transferring or bottling wine. Volumes generally range from 21 gallons (80 L) to 264 gallons (1,000 L) and more. For example, the price of a 52-gallon (200-liter) tank starts at just under $400.

If you intend to macerate, pump-over the fermenting juice, and transfer grapes and must in and out of your tank by using a man-way door and valves, you might consider a deluxe fixed-volume tank. Optional features include: conical bottom with discharge valve, racking valve, sampling valve, level indicator, top and bottom man-way doors, cooling jacket with thermometer and stainless-steel sprinkler for pump-over. These souped-up stainless tanks are used in commercial wineries and available volumes usually start at 264 gallons (1,000 L), but smaller models with a few key options, such as a recirculation pump, can be found or custom-made. Many retailers also carry much simpler conical fermenters. Made of plastic or stainless, they typically are outfitted with a racking arm and a ball valve for removing lees. They start in volumes as small as 6.5 gallons and cost as little as $100 for a plastic model.

Oak barrels have long been used for aging wine to add aromas, structure and overall complexity. The practice of barrel fermentation usually applies to white winemaking, since it is not practical to conduct maceration in barrels for red wine. Getting the grape solids in and out of barrels is a near impossible task; however, conducting malolactic fermentation (following alcoholic fermentation and maceration) in barrels enhances the complexity of a red wine. Kit wines or wines from juice can be fermented in barrels since they require no maceration.

Two key points to consider when purchasing barrels are oak type and volume. The most widely available barrels are made from American, Hungarian and French oak in increasing order of cost. The best (and most expensive) oak barrels have a very tight grain, which impart flavors and aromas in a slower and more subtle fashion. Most barrels are toasted on the inside, and the toast level is a key factor during the aging process. Choose the toast level — light, medium, or high — to suit your taste. A medium toast level seems to provide the right balance in flavors. The highest level imparts pronounced oak flavors, which may not appeal to everyone.

Barrels used in commercial wineries may look attractive, but the 59-gallon (225-L) size is cumbersome. Although larger barrels are recommended because they provide a better and slower aging medium (due to the smaller surface-to-volume ratio), 15-gallon (57-liter) barrels offer a good compromise. A 15-gallon American oak barrel costs approximately $150 while its French counterpart costs a minimum of $200.

Pumps

As you increase your annual wine production, you will soon realize how much time and effort is spent on racking and transferring wine between containers. A good pump is a must.

If you intend to simply transfer wine, not must that includes grape solids, with an annual production of up to 50 gallons (200 L), a diaphragm pump — such as a variable speed, 1/4-horsepower Flojet pump with 1/2-inch tubing — is ideal, and costs $100-150. It can displace wine at a rate of up to 4 gallons (15 L) per minute.

For larger production, you will need a heavy-duty diaphragm, impeller or centrifugal pump. Diaphragm pumps use mechanical suction to displace wine, and can run dry for an extended period of time, meaning that they will not be damaged if they are left accidentally to run without displacing any wine. They also have less wear and tear and therefore last longer. Impeller pumps use a rotating device, consisting of blades, to displace wine and grape solids by suction, and cannot be left to run dry. They are most efficient for displacing grape solids, whereas centrifugal pumps are best for displacing wine without solids. Centrifugal pumps generate their pumping action by imparting a centrifugal force to the wine, as opposed to a suction force. Variable-speed pumps can also be very useful to control the rate of displacement.

Choose a model with a minimum of 1 horsepower equipped with 1-1/2 inch (minimum) fittings to accommodate winery-grade hoses for such applications as pump-over of juice and grape solids during maceration and fermentation. If your winemaking includes stems, upgrade fittings and hoses to 3 inches minimum.

Typical 1-1/2 inch impeller pumps can displace 25-50 gallons (100-200 L) of wine per minute, and cost $700-1,000 or more. These pumps are self-priming, meaning that you simply turn on the motor to start transferring wine. Pumps that require priming require that the pump cavity be filled with wine before the pump is turned on; otherwise, there is no suction. Many centrifugal pump types require priming.

Filtering

The decision to filter wine is mainly personal, although sweet wines or problem wines, from which residual yeast needs to be removed to prevent bottle re-fermentation or spoilage, require filtration prior to bottling. Early drinking wines may also need to be filtered because their quick production may not have allowed for full clarification. Otherwise, clean and clear wine can be obtained through natural sedimentation or fining agents.

Filtering consists of passing wine through a filter medium by mechanical or pump action. Mechanical filters can be labor-intensive for large batches, so I recommend a system equipped with a pump. The most common filter medium in home winemaking is the depth filter pad, manufactured from cellulose fibers, which filters out particles throughout and across the pads. The size of particles filtered depends on the rating of the pad, expressed in microns; the higher the rating, the smaller the particles that are allowed to pass through.

There is a plethora of filter system models from countless manufacturers. Filtering efficiency is the main factor to consider. Efficiency mainly depends on the total volume from all filter pads in a given system, as well as the pump. A system with a greater number of pads and larger pads will provide a greater filtering surface, therefore increasing capacity. Otherwise, you may need to change pads during filtering if they start to clog up. A system equipped with a pressure gauge will prove helpful to determine when to change pads. The pump also plays an important role in overall efficiency. It should be matched to the filter system configuration (mainly pad volume). Some systems may have a pump that is too small or too large, which affects efficiency.

If you are considering buying a filter system, talk to retailers or other winemakers who can offer opinions based on experience. Ask a lot of questions regarding the pump. For example: What is the capacity? What type is it — diaphragm, impeller or centrifugal — and does it require priming? Can the pump be used in bypass mode to allow for simple transfer of wine? A bypass system is a good way to minimize your investment by using the pump for transferring wine or for filtering.

Bottling and Corking

Now that you have made all this great wine, you are faced with the daunting task of bottling it. Bottle rinsing and sterilization, bottling, corking, capsuling and labeling … it can be overwhelming.

For smaller productions, devices for filling one bottle at a time are adequate. A popular model is the automatic filler ($20) that operates by gravity and fills every bottle to the same level. Pump-operated automatic fillers ($200-250) can increase efficiency.

For larger productions, bottling speed can be significantly increased by upgrading to a multi-spout filler for filling between 3 and 8 bottles at the same time. The multi-spout filler consists of a small holding tank fed by gravity from a larger container, a float valve to control flow of wine into the holding tank, and spouts. Its operation is very simple: a bottle is placed under each spout (the spout must be primed by siphoning wine similar to when using a racking hose) until it is filled to an adjustable, predetermined fill level.

I have found the 3-spout filler to be a good compromise between cost (approximately $300) and speed (250 bottles per hour, on average) if you are working alone — a 3-bottle cycle seems to match two hands very well. Choose a stainless-steel model; they are very easy to clean and will not rust.

Corking still remains a serial operation unless you invite friends over to help out. But with a good quality floor corker, you can cork 250 bottles in less than 30 minutes. At a cost of $50-100 depending on the model, this is a small investment with a quick payback.

Choose a model that will easily accommodate a wide variety of bottle sizes such as half bottles, magnums and double magnums.

“Capsuling” (shrinking capsules used to dress the top of bottles) can be accomplished using a heat source such as a hair dryer or steam from a kettle. These are adequate for small productions but would require too much time for larger productions, even as small as 200 bottles. One of my favorite “toys” is the hand-held heat tunnel. At approximately $250-300, it is the best investment if you need to shrink capsules for a few hundreds of bottles.

The heat tunnel is placed over the capsule momentarily (two seconds) to shrink the capsule, before moving on to the next bottle. It’s that easy! Shrinking 250 capsules is now a matter of 10-15 minutes. Be sure to apply heat only momentarily and avoid touching the capsule with the heating element to avoid damaging the capsule, particularly the type with a tab.

Lab Equipment

A properly equipped home laboratory will greatly enhance your wine analysis efficiency and test accuracy. The small investment in useful laboratory tools will provide a quick payback.

A good balance, for example, with a 400-gram (14-ounce) capacity and 0.1 gram resolution, will prove to be an indispensable tool for measuring chemicals and a welcome replacement for the high-error teaspoon and tablespoon. A good digital balance costs around $150.

Staying on top of your wine’s total acidity (TA) and pH levels is important to ensure trouble-free winemaking. Invest in a good pH meter ($50) providing measurement with 0.1 unit resolution and accuracy; pH meters with 0.01 resolution and accuracy offer more accurate results although they are expensive ($150 and more).

Strips of special paper to measure pH are also available. A strip is immersed in a wine sample, and then the color that develops on the strip is compared to a standard color chart. Unfortunately, commonly available pH strips are very inaccurate, with results varying by as much as 1 pH unit, which is too significant for winemaking. You can seek pH strips from specialized laboratory suppliers that provide more accurate results. The pH meter is still the better investment that will repay itself over time.

If you operate a home vineyard or you would like to verify the Brix (sugar concentration) level of grapes you purchase, a refractometer will come in handy. Only a single drop of juice is needed to measure the Brix level quickly and efficiently. The reading is obtained by holding the device up in bright light. Be sure to take readings from outer as well as inner berries from a grape cluster. Outer berries have been exposed longer to the sun and will therefore have a higher Brix reading. A good, basic hand refractometer costs less than $200.

Your home lab should also include kits for total titratable acidity (TA) tests, malolactic determination by paper chromatography, and SO2 tests. Be sure to stock sufficient chemicals and that these are always fresh. Also stock some critical chemicals to address unexpected winemaking problems. The list should include potassium metabisulfite (for sanitizing or preserving wine), tartaric acid (for increasing TA and decreasing pH), sodium hydroxide and phenolphthalein (for measuring TA), buffer solutions (for calibrating pH meters), potassium sorbate (for preventing renewed bottle fermentation), and extra packets of yeast cultures and yeast nutrients.

Lifting Equipment

You will most likely be moving large containers around in your home winery, and you may also store demijohns on shelves high above floor level. So a hoist and trolley for carrying and lifting heavy containers is a must. If you are a handyman, this seems like a good do-it-yourself project while waiting for all that wine to age.