One of the most enduring — and evocative — images in the winemaking world is that of the barrel room. Virtually every commercial vintner has one, and it’s among the “must sees” on any winery tour. Besides its symmetrical beauty and photo-op appeal, the barrel room indicates that the vintner is shooting for an elusive quality in his wine. Barrel aging is one of the common denominators in wines that reach beyond the ordinary.

One of the most enduring — and evocative — images in the winemaking world is that of the barrel room. Virtually every commercial vintner has one, and it’s among the “must sees” on any winery tour. Besides its symmetrical beauty and photo-op appeal, the barrel room indicates that the vintner is shooting for an elusive quality in his wine. Barrel aging is one of the common denominators in wines that reach beyond the ordinary.

Although the use of barrels is traditional in fine winemaking, it is also a labor-intensive and potentially troublesome part of the process. So why should you, as an amateur, consider aging your wine in oak?

Well, first of all, because you will be enhancing the quality of your wine; and also because, if you are a traditionalist, you will be following in the footsteps of winemakers who date back at least 2,500 years. By buying a five-gallon (19 liter) barrel, a home hobbyist can produce wines that rival the finest of Europe — or any other region, for that matter.

Barrels cost more than glass carboys — a five-gallon barrel might cost as much as $200, not including shipping. Plus, they’re harder than carboys to use, handle, maintain and keep clean. But the extra effort will be well-rewarded, because a good barrel can make a tremendous difference in the quality of your wine. To a red, it conveys a softness and complexity that adds great character, due to the conversion of harsh tannins to softer polymers; to some whites — particularly Chardonnays and similar wines — it can give additional aromatic qualities that make the wine special. Two weeks in a barrel can mature a white wine as much as a year in a carboy would have done, and in the process confer a delicate but attractive oakiness that announces the wine as truly “commercial” in character.

Barrels have been around almost as long as winemaking has; Caeser Augustus recorded their use as early as 50 B.C. The alternative for early winemakers, the earthenware amphora, was heavier, harder to store, difficult to seal, and more breakable than a wooden barrel. For centuries, barrels remained the only closed vessel that was practical and affordable for wine storage. (Barrels have only been used to “flavor” wine for the past 200 years or so.) Today the winemaker can choose among stainless-steel pressure tanks, glass, plastic and concrete vessels in a range of sizes, but wooden barrels retain their traditional appeal.

How Barrels Are Made

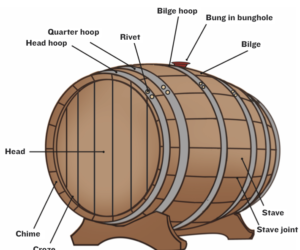

Barrels are simple things, but the skill required to make them is no longer as readily available as it once was. Barrels are constructed of many separate, fitted pieces of wood — called staves — and end pieces fitted in a circular shape. All of these pieces are forced together (usually being bent while heated) and held in place by a series of metal hoops.

No nails or other fastening are used, except for a few tacks to hold the hoops in place. Dried straw or rushes may be placed between the staves or end strips to help the seal, but in essence the barrel is waterproof because the pieces fit tightly against one against the other. When the barrel is filled with liquid, the wood swells slightly, effectively completing the seal.

French and American Barrels

Barrels are typically made of oak (although some other woods, such as redwood or cedar, are sometimes used), with the very best oak considered to be that from the French forests of Limousin and Nevers. In the French method, the staves are split from the timber using an axe, piled in stacks in the open and allowed to season for 1 to 2 years. Exposure to sun and rain results in the sap being thoroughly removed. After this time the rough staves are individually shaped by the cooper, one barrel end is constructed, and then the staves are made pliable by being placed over a low fire. When the heat has done its work the staves are bent into place and the first hoop fitted. The process is repeated at the other end, and a second hoop fitted there. The third, fourth, fifth and sixth hoops, each pair progressively larger than the previous, are placed at alternate ends and driven tightly up the staves, then tacked in place.

The traditional American practice was to saw the staves from the timber, dry them in a kiln, and then form them into shape using live steam. This certainly made the whole process a lot faster, but it was found that wines aged in them exhibited an excessive “green wood” or sappy quality. For a number of years this was ascribed to the use of American, rather than French, oak.

A few years ago, however, the Robert Mondavi vineyards in California undertook an extensive experiment using French barrels, barrels made in the traditional American manner, and barrels made from American oak using the French technique. It was discovered — and this has been borne out in numerous blindfold tests — that there is little distinguishable difference between the flavor conferred by barrels made from American oak and those made from French oak, provided that the oak is treated in the same way — split rather than sawed, air dried, and formed over a low fire — and that the oak comes from a similar latitude (which determines the density of the wood).

The French method of construction produces a softer result, a fact based on the internal structure of wood. Wood, being produced by a living plant, is composed of a series of cells. These are long and tubular, and are all aligned in the same direction. When the wood is split, it naturally cleaves along the grain, revealing only the sealed outer surface of the cells. Air drying allows all of the sap to be removed, and softening it over low heat results in a slight browning or “toasting” of the wood surface.

In the traditional American manner, when the wood is sawed, it is equally possible that the surface will be cross-grain, exposing the cut ends of the cells. Consequently any liquid placed in it — such as wine — will itself be exposed to the bitter material within the cells themselves. In addition, kiln drying, rather than removing the sap, may tend to seal it in, and steam heating confers no equivalent to the light toast of the European barrels.

Light and Dark Toast

The degree of “toasting” depends on a couple of factors. First is the size of the barrels; those of longer curvature — such as Bordeaux barrels — require less heat. The heat is generated by open fire, to bend the staves to the appropriate dimension. Those which are stubbier, such as Burgundy barrels, require greater exposure to the fire, and therefore have a greater degree of burning, or “toast.” Heavy toast — or charring — is seldom used in quality wines, although some ports and sherries may use them. It turns out that, properly constructed, North American oak barrels can simulate either Burgundy or Bordeaux characteristics, depending on the style of manufacture.

The other choice in degree of toast is, of course, the buyer’s preference. In the former case, one would correctly assume that Bordeaux barrels — and therefore the wines of Bordeaux lineage, such as Cab Sauvignon, Cab Franc, and Merlot — would require a barrel with lighter “toasting,” while those from Pinot Noir and Gamay families would benefit from a shorter barrel with heavier toast. Chardonnays would require minimal “toast” and minimal time in the barrel. (That said, we’re all familiar with the “big Chards: of the USA and Australia; they have huge oak character, compared to the French Chablis, which exhibits virtually none.)

How Barrels Make Better Wine

When a young wine is placed is placed in a barrel, a number of things occur. The first, and most important, is that the alcohol in the wine leaches from the wood a number of complex tannins and vanillins that enter into the flavor profile of the wine (this is the primary reason why cross-grain wood is undesirable).

The rate at which the leaching occurs depends on the strength of the wine. The rate increases with increasing alcohol content, up to 40 percent, which is in the range of liquors rather than wine. The rate also depends on the age of the barrel — in other words, the number of times it has previously been used — since that will obviously affect the amount of tannin left in the wood and the depth at which it is found. The greater the age of the barrel, the longer wine needs to remain in it, in order to obtain a given level of oakiness.

On thinking about it, one will conclude that the surface area of the barrel is important as well, since a larger surface area means more wood surface from which to extract tannins and vanillins. If you remember your high-school geometry class, you will recall that as a container (a cube, sphere, or what have you) increases in size, the volume increases faster than the surface area. This means that smaller barrels have a larger surface area, compared to volume, than do larger ones, and therefore that smaller ones confer oakiness faster than do larger ones.

There is an old theory that barrels allow a wine to age gradually because of the slow infiltration of air through the wood. This has been disputed lately, and I agree with those who dispute it. Wine in a barrel will slowly lose volume because of evaporation through the wood; the theory here is that in a damp environment it loses alcohol, while in a drier one it loses water. In any event, the level does drop, and the winemaker is obliged periodically to add wine to eliminate the “ullage,” or missing wine.

I have found that, if the barrel is fitted with a fermentation lock, the lock reverses as the ullage develops, indicating that the interior of the barrel is at lower pressure than the outside. I’m of the opinion that the barrel is essentially air-tight, and the only air that enters does so when the bung is removed to top-up the ullage.

Buying a Barrel: The Basics

Barrels are generally available in anything from the full commercial size (typically 59 gallons or 225 liters) to the more affordable and practical 5-gallon (19-liter) size. Many home winemaking supply shops carry barrels or can order one. In addition, a handful of North American specialty shops make or import small barrels and will ship them to you.

A third source may exist in your area: Some religious supply houses import mass wine in barrels and bottle it for churches. These barrels are sometimes available at moderate cost, although you have no way of knowing — short of constantly telephoning the store — when they will be available. If you find one, make sure that the barrel is not vinegary to the smell; if it is, pass it by, as recovering it is altogether too much trouble and fraught with danger. Also ensure that it’s not coated internally with paraffin or other sealants, because if it is, the primary reason for using it — the contact between wine and wood — is lost. Some wine supply dealers may also stock used barrels. Again, check to ensure that they are not coated on the interior; a look through the bung-hole with a flashlight, and a money-back guarantee, are worth your while.

A potential fourth source, but the least recommended, is food importers who may periodically advertise barrels for sale. Be very cautious about these; almost invariably they are paraffin-coated and previously used for storing olives or such like. If this is the case they are useless to the home winemaker, other than as planters or bar stools.

How to Treat Your Barrel

Barrels are expensive, and somewhat tricky, propositions, so it’s a good idea to ensure that whoever you buy a barrel from will stand behind it and refund your money if it turns out to be a lemon. Before purchasing it, ensure that it has a sweet or neutral smell, rather than a vinegary one. I’d personally avoid a barrel made in the “traditional” American way, which may be rough to the touch, will show no sign of “toasting” of the interior, and may have a “green wood” smell about it.

When you get your barrel home, the first thing to do is to make a “cradle” for it. This is a supporting device — which can be as simple as piece of two-by-four cut on a 45-degree angle and fastened to a brace — which will hold the barrel under the middle hoop at each end. When building the cradle, remember that the barrel’s weight should be borne by the hoops, not by the staves, since that would distort the staves and result in leakage.

The barrel is set with the bung-hole uppermost. It should now be filled with a solution of warm water and sodium or potassium metabisulphite, at the rate of 5 ml of metabisulphite per 20 liters of barrel capacity. Once it’s filled, fit in a stopper. The barrel will likely leak slowly for a few days until the staves have swelled, and should be topped up regularly. After a week, at most, it should stop leaking. If it continues to leak after this time, there are a couple of options. One is to return it to your supplier and get your money back. The alternative is to try to fix it yourself. If the leak is minor, this may be preferable to the hassle of arguing with your supplier.

The first step is to hammer the end hoop — on the end from which the barrel is leaking — farther onto the barrel. This will increase the pressure and may stop minor seepage. The second step, if this doesn’t do the trick or if the supplier does not give you satisfaction, is to try to seal the leak. I’ve had success using a tar-based roofing compound around the outer circumference of the end-piece, on the outside of the barrel. If trying this approach, make sure it is indeed a tar-based product. Since you may not use the same compound I did, nor necessarily use it in the same way, you’re on your own if you try this; nonetheless, it worked for me.

Using Your Barrel

You’ve bought your barrel and verified that it smells sweet. It’s now set up on a cradle, with only the hoops in contact with the supports; it’s been filled with a metabisulphite solution; and it’s no longer leaking. What now?

The first step is drain it, heave it over to the sink and use a bottle washer on the inside to flush out any remaining sawdust or debris from the manufacturing process. Failing this, take it out to the driveway and flush it thoroughly with a garden hose. Then put it back on its cradle, bung uppermost.

For the first filling we suggest using a wine of reasonable quality, but not your best, as it’s easy to overdo the contact period the first time you use a barrel. Fit a stopper or airlock into the bung, and leave it. For how long? Well, that depends on the newness of the barrel, its size, and the type of wine you are making. By way of example, a five-gallon (19 liter) New American Oak Burgundy-style barrel made in the European manner will confer as much oakiness as anyone could want on a white wine in less than two weeks. On the other hand, I have a 15-gallon (56-liter) barrel that has been used for the past twenty years, and in which a red wine needs 18 months to extract adequate oak. Check progress periodically by tasting a small sample of the wine and, when you are satisfied with the flavor, bottle it. Don’t forget to check for “ullage” and top up the barrel as required during the aging process.

If you have planned ahead, you will have another wine ready to go into the barrel; if so, rinse out the barrel and immediately refill it with wine. If not, rinse it out and fill it with water and sulphite, as you would a new barrel. Check it periodically to ensure that there is still a sulphite smell in the liquid. Replace the sulphite solution every three months, if the barrel stays empty that long.

It is a good idea to “dedicate” a barrel to either white, red or sherry-style wines. Red wines will stain the wood, and this will carry over to a white wine, while sherries impart a particular flavor which tastes odd in other wines. Having said this, some winemakers (me included) have found that if a barrel is not too badly tainted by color or sherry flavor, it can be restored by the use of chlorine bleach and extensive flushing with water. Such a barrel may not be suitable thereafter for the finest wines, but may suffice for ordinary wines.

Some winemakers also set up a “progression” of barrels. Barrels begin life as a white wine barrel, then after several uses are converted to a red wine barrel, with correspondingly longer contact time, then finish life as a sherry butt. The theory behind this is that after a few uses the flavor of the barrel is gone. I do not fully subscribe to this view. Visitors to French cellars — or, for that matter, to Pelee Island Winery in Harrow, Ontario — will find barrels in use that date back over a hundred years. That said, most winemakers do believe that barrels lose their ability to impart flavors after a number of years of use. Older barrels may be used for their soft and gentle environment, which lends itself more to aging than flavor extraction.

The wine will require a progressively longer time in the barrel to acquire the full oak taste, and in the case of the oldest barrels this may simply become impractical, and the oldest barrels are probably more for aging than for organoleptic achievement. However all is not lost; to make a relatively young, but well-used barrel close to new in condition again —to reacquire maximum effect in a reasonable period of time — it is possible to “recooper” it, once or possibly twice depending on the thickness of the wood. This involves partially disassembling the barrel by an expert, and shaving the inside surface to remove the leached-out inner surfaces.

In addition, older barrels may be given a new lease on life by the “inner stave” technique. The bottom line is that the useful life of a barrel can be extended in more than one way. Anyone who tells you that after a half-dozen uses a barrel is “used up” is either talking through his hat … or selling barrels!

Barrel Alternatives: Other easy ways to oak your wine

If you’d rather not buy a barrel, there are easier and less expensive ways to add oak to your wine. One is the use of oak extract to simulate the barrel oak; another is the addition of oak chips to the wine, and the third is “oak sticks” of toasted French oak to place in the wine.

OAK EXTRACT: Of the three, oak extract is the least satisfactory. It creates some oak flavor, but if enough is used to be truly noticeable it may leave a harsh taste. It is, however, fast and easy to use. Extract is produced commercially by steeping oak in alcohol, which is then bottled. You can buy oak extract at a home winemaking shop; the bottle will tell you how much to add.

OAK CHIPS: Oak chips give a bit more oak flavor but they are messy to remove, may be of doubtful sterility, and sometimes contain amounts of sawdust that are hard to remove from the wine. On the other hand, it is possible to buy high-quality French oak chips — actually, oak shavings rather than the cheap sawdust — from Nevers, Limousin and other French oak forests. Toasting them in the oven — make sure you don’t over-toast or burn them — can intensify the flavors, and at their best they are little indistinguishable from barrel tannins.

Contrary to popular belief, there is no optimum time to leave them in a wine; because they are so thin, most of the available tannins are leached out within 48 hours. Leaving them in the wine longer does not increase the oak effect, nor does it seem to impair it. The quantity you use is in part a matter of personal preference, based on the degree of oakiness you wish to have, but as a rule of thumb a white wine will typically use 3 grams of chips per liter of wine (roughly two ounces in 5 gallons), while reds would benefit from 5 or 6 grams per liter.

Here’s a tip: If you do use oak chips, rinse them either in water or (preferably) sulphite solution before putting them in the wine. This will remove loose sawdust particles which can be difficult to separate from the wine. Using sulphite solution will also lessen the risk of infection from bacteria and other nasties.

OAK STICKS: The best of the three is toasted “oak sticks.” If these have been properly produced they are split, not sawed from the lumber, with smooth surfaces on all sides. Typically, they’re about one inch square by about one foot long. They should be sterilized by rinsing in a strong sulphite solution (similar to the one used to precondition a new barrel), then split lengthwise using an axe into smaller pieces to increase the surface area available to the wine. These are then placed in the wine for several weeks (again, periodically testing the wine by taste after the first 2-3 weeks is recommended). This will produce a noticeable oakiness not unlike that from a barrel and has been referred to as “putting the barrel in the wine, rather than the wine in the barrel.”

In Australia, several quality vineyards use what is termed an “inner stave” technique; when a barrel is reaching the end of its useful life, new sticks — appropriately split, dried and toasted — are inserted in a plastic mesh to line the inner surface of the barrel. The claim, which I would not dispute, is that this is close to equalling a fresh barrel.