Volatile Acidity

One of the most common wine flaws is an excessive amount of acetic acid, which is also called volatile acidity (VA). The primary cause of acetic acid, or vinegar, in wine is oxidation of ethanol by Acetobacter, a bacterium that thrives in the presence of oxygen. Since Acetobacter is present everywhere — on grape skins, in your winery, and simply floating in the air — winemakers must be vigilant in not exposing wine to the bacteria for extended periods of time. Some spoilage yeasts are also capable of producing acetic acid. And even S. cerevisiae yeast that you use in making wine produces a little acetic acid, which actually is considered beneficial in adding aroma complexity.

Taste and detection

Volatile acidity is present in all wines to varying degrees but it should not be detectable, ever. If you are making wine to enter into competition, it is best to keep the VA low as a judge will probably score your wine poorly if he or she detects it in your wine.

Technically, the threshold for detecting acetic acid in wine is around 700 mg/L; over this threshold the wine becomes objectionable, and anything over 2.0 g/L is considered spoiled as the wine will taste, well, like vinegar. To self diagnose the presence of acetic acid in your wine, look for a distinctive aroma of vinegar, and if you detect a smell of glue or nail polish remover, that’s ethyl acetate, which is the next stage of acetic acid spoilage and the wine is lost.

Prevention

While it is impossible to completely prevent VA, there are ways to control it in your homemade wine.

Acetobacter cannot thrive without oxygen present, so control it by leaving little to no air at the top of your winemaking vessels after primary fermentation until bottling. (Oxygen is driven out during primary fermentation by the large amount of CO2 produced by the yeast converting sugar into alcohol.) Reduce headspace by adding water or wine to fill the vessel, or, if you have a small batch, you can drop sanitized glass marbles into the container until the airspace is gone. You can also transfer the wine to a smaller container or top with an inert gas, like argon. Be sure to keep your SO2 levels at the proper levels, especially at high pH when bacteria thrive the most, which will prevent oxidation as well as help keep spoilage yeast and bacteria populations under control.

Keep your fermentation temperatures on the cool side. Acetic acid bacteria prefer warmer temperatures and will produce more of it when fermenting any higher than 75 °F (24 °C). Warmer temperatures might be necessary for the particular wine or yeast strain you are using, but just be aware that warmer temperatures raise your chances of VA. If you have ongoing problems with VA, try performing cooler fermentations.

Another way to prevent excessive VA is the always-recommended practice of keeping your winemaking equipment and winery as clean and sanitized as possible. Also, keep fruit flies under control as they are known for transferring Acetobacter from place to place, and avoid opening carboys or fermenters as much as possible; every time you expose your wine to the air you risk introducing Acetobacter.

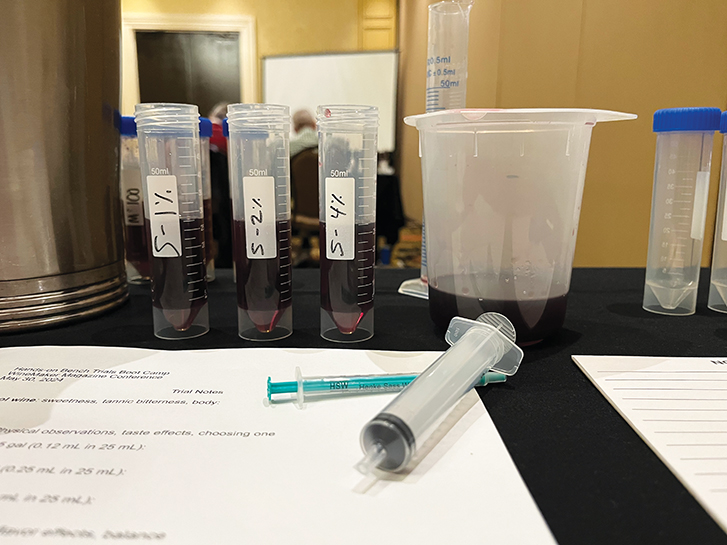

Treatment

As with any wine flaw, try to catch excessive VA early, or you’re sunk. If you detect small amounts of it early in the winemaking process, rack the wine to a different vessel and adjust the SO2 levels if they are low. If you detect too much VA it in a finished wine, the best way to deal with it is to blend it with another wine. Do small-scale (bench) trials to see if you can blend the VA away before treating an entire batch of wine as it might not be worth saving — or worth wasting your good, unaffected wine — if a batch is too far gone.