Choosing A Wine Press

Aside from a container to hold your wine, a press is arguably the next most crucial piece of equipment for making wine from fresh grapes. Beyond simply squeezing the must or wine out of your grapes, you can fine-tune your wine’s style depending on what type of press you use and how you use it. Different presses and pressing techniques will lead to — in both whites and reds — more phenolics and varying degrees of oxygen exposure.

One can theoretically make due without a press for red wine production, utilizing only free run juice (which some winemakers prefer), losing approximately 15% of the year’s yield and sacrificing the extra tannin and color that come from press run wine. With whites, however, there’s pretty much no way around it: You need a press. I did not accept this fact my first time making white wine, instead choosing to stomp the grapes by foot and squeeze them out in a strainer bag. This turned out to be unwise, as it was days until I could hold a pen steady from squeezing so much!

History of the Press

The history of winemaking is probably not much longer than the history of the wine press. Many early wine cultures loved and revered wine to the extent of worshiping wine deities, so it’s hard to imagine they didn’t want to get out every last drop!

The earliest presses were not always machines to squeeze wine from grapes as we think of today, they were simply tanks of one material or another where the grapes could be crushed by foot and the must would drain to a receptacle below. The technologically advanced version of this was laying wooden beams on top of the must and adding weight on top of them. In Egypt, after treading grapes, the remaining skins would be put into a cloth sack, which was then twisted from both ends to wring out as much juice as possible.

In Gods, Men and Wine by William Younger, we’re told that mechanical presses became more common in the second century BCE, in the hands of the Romans. In some parts of ancient Europe, particularly what is now Italy, the beam press and the screw press (essentially the basket press) were being used and continued to be used for the following 18 centuries! (Do an internet image search on the beam press, it’s a shockingly massive piece of equipment.) Both of these presses employ increasing weight from above to apply pressure downward onto grapes or must.

The screw/basket press remained the standard until the 1940s, when variations of the basket press began to be developed, leading to the other types of presses we now see in commercial wineries today: Membrane and bladder (in addition to the

basket press).

This means that wine press technology was static from the Romans until the mid-20th century, and that the new technology, and the variations we have today, are all based on this ancient design. Profound on the one hand, while on the other hand, the need has remained the same: Squeezing must out of grapes!

The continuous press made a brief cameo in the 20th century and is now rare and considered obsolete. It consists of a screw that narrows down its length, little by little tearing and squeezing the grapes or pomace together, separating must/wine and skins. This type of press was employed by larger wineries in the past, and gives must/juice with very high levels of suspended solids, due to the tearing, which often required clarification of some type. The major advantage with the continuous press is that it is continuous — all other presses must be filled, pressed, emptied, and refilled — the continuous press can just keep going.

The presses of today

Membrane presses have become the most common choice in most medium and large wineries. They consist of a closed cylinder, with an inflatable tarp inside that presses grapes against a perforated wall of the cylinder. The pressure and pace of the pressing is easily controllable by computer, and of all the presses, membrane presses protect the must or wine from oxygen more than any other — this is not an advantage or disadvantage, but of course has different effects on red and white wines, and therefore different stylistic effects on both. However, the membrane press is not really an option for most home winemakers, as they’re large, require an industrial electricity setup, and even the smallest sizes start at around $20,000!

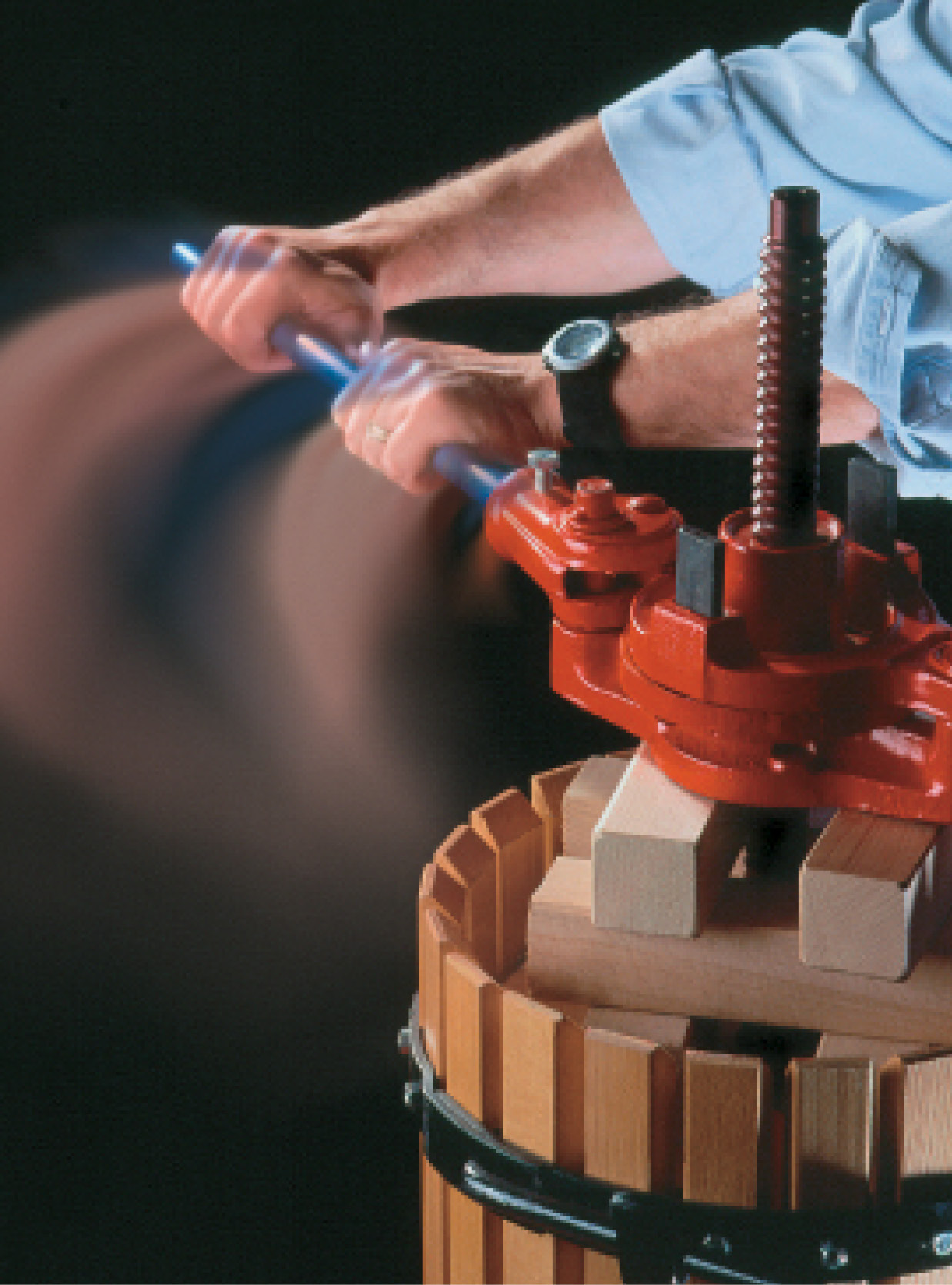

As a home winemaker, your two primary options are the basket and bladder press. Despite the names, both types of press have a basket, however the basket press presses down on the grapes inside the basket from above, and the bladder press has an inflatable bladder centered inside the basket that inflates outward, pressing the grapes against the basket.

For the home winemaker, both basket and bladder presses are fantastic, and from a quality standpoint, you cannot go wrong. Both types of presses exert relatively gentle pressure and give short distances for the juice or wine to travel, which minimizes solids in wine. As a result, you’ll have less solids to rack off of — especially crucial for reds — as you minimize grape bits and solids that can encourage the formation of hydrogen sulfide.

The main difference for the home winemaker between basket and bladder presses is one of cost versus convenience. At the time of writing, basket presses from some of the larger home winemaking suppliers range from $255 for a 2.5-gallon (9.5-L) to $890 for a 45-gallon (170-L) press. Bladder presses range from $765 for 5.3-gallon (20-L) to $2,340 for a rotating 47.5-gallon (180-L) model (larger models are available as well).

Basket presses are much less expensive, but are slower and require much more physical effort. To use a basket press, you must ratchet down the ram (the ram is the two part lid-like component that is in contact with the grapes and exerts the pressure), little by little, along a screw running up the center of the basket, over a period of hours. You will work up a sweat and be tired afterward (the old adage “it takes a lot of beer to make wine” comes to mind). The benefit this has is that the process is inherently slow and gentle — with my whites, I gladly take hours to press very slowly, minimizing tearing grapes and the release of phenolics.

With reds, as pressure is applied little by little, and you will not have a pressure gauge, press fractions cannot be based on the amount of pressure, so tasting is necessary to decide what to include in the current fraction, and when to begin another one. Though more work, this is an exceptional opportunity to get to know how the wine is changing with the increased pressure and to contemplate how you want to blend, knowledge which might otherwise be forgone with more convenient equipment.

In contrast to this, with a home bladder press, you attach your garden hose, turn on the water and then shut it off once you’ve reached your desired pressure, which you can read on a pressure gauge, turning the water back on as needed to increase pressure. You can do a quick pressing, moving the pressure up rapidly, or drag it out as long as you like. Pressures can get high, to three plus bars (43.5 psi, pounds per square inch), way more than is needed. The commercial membrane press I use only goes up to two bars (29 psi) (I personally press whites to one bar (14.5 psi) and reds, in two or three fractions that I keep separate, to two (29 psi).

As basket presses exert pressure on the must downward, perpendicular to the direction the wine travels (outward), and as the radius of the cake produced is large, some wine can get locked up closer to the center of the press cake (the compressed mass of skins and seeds), and if you want to get out every drop, it will likely be necessary to break up the cake and repress it to do so, adding lots of time (and, to the second pressing, solids).

As the bladder design has a bladder inflating in the center pressing outward in the same direction the wine must travel, there is a shorter distance for the deepest wine to travel, and a full pressing is possible in a single pressing.

Further, and tying this together with price, you may not necessarily need as big a bladder press as you would a basket press. Because you are able to press much faster with the bladder press, and can get all the wine out in one pressing, depending on how long you like to press for you may be able to do numerous pressings in a smaller (and therefore less expensive) bladder press as fast as you could in a single, larger basket press.

In the cleaning department, the bladder press has an edge over the basket as well. First, the basket on bladder presses will be stainless steel, always the best for cleaning. The basket press will likely have wooden slats, and although they look much more romantic than the cold steel, wood being porous can harbor spoilage bacteria and yeasts, the same way a barrel can. That being said, I have rented a press from the local winemaking shop many times that was very used and I can’t imagine that every renter was a diligent cleaner, but I never had any issues and my wines always came out healthy and clean.

The good news is that you can’t go wrong. Whether you opt for the more ancient and labor-intensive design, or splurge and go with modern convenience, both presses will turn out a great wine. Although membrane presses are the most common in commercial wineries today, more and more winemakers are opting to go with basket press style presses, for their more gentle action, and for the extra exposure to oxygen for reds at the time of pressing.