These are the quiet moments in the vineyard and the cellar. Wines are dry or bubbling softly through malolactic fermentation, and there is time to reflect. A key consideration at this juncture is to pay attention to developing wine quality and to use successes and failures to help guide our plan in the vineyard for the upcoming growing season.

I often make the humorous anecdote: “I retired from a lucrative career in public education, and leveraged it into a professional wine career. In other words, the kids drove me to drink, and I went pro.” Embedded in this joke is some truth: Your wine from last vintage is a report card and giving yourself an honest grade can create a valuable feedback loop for the small vineyard.

Understanding your wine’s qualities (and deficits) is both easy and difficult. It’s easy if you have a long track record with your vineyard and wines made from it (familiarity), and difficult because wine is among the most complex matrices on planet Earth.

The focus in this column is to celebrate and honor our vineyards by digging deep into their fruits and how they fermented, to separate what our cellar practices create versus the results of our vineyard management. Through education, trials, tasting, and consideration, we have an amazing opportunity to improve our vineyards in this year and automatically improve the potential quality of our wines.

This is a whole lot of work: Planning, planting, managing, laboring in the vineyard, and the dozens of decisions on how to make wine out of our precious fruit. Putting in another few hours to parse the relationship between vineyard management and wine quality is a no-brainer, so let’s get started with the process of turning tasting notes into meaningful labor for vineyard improvement.

Establishing a Post-Harvest Evaluation Ritual

Timing

Tasting young wines can be challenging; as we all know they change every week. Finding the correct time to taste and consider quality as it emerges from the vineyard is crucial, and can be a little frustrating, as pruning usually is completed before the wines finish malolactic fermentation and have flavors that we would define as “complete.”

Here are my suggestions:

• Taste your wines from barrel/carboy, etc. after primary fermentation has completed (the wines are as dry as you want them), but before making final decisions on a management plan for the upcoming year. This will usually fall in late winter, before pruning must be completed, and definitely before budbreak.

• Get a notebook (or file on your computer) that organizes the written evaluations of your wines through fermentation and aging. You can track fermentation times, flavors, aromas, yeasts, malolactic bacteria chosen (if any), and tasting notes throughout the wine’s fermenting/bottling/aging.

• In the same notebook you can also make generalizations (through data) about the vintages. Hot, cool, wet, dry, etc.? When did you complete pruning, suckering, shoot positioning, fertilization, etc.? When was full canopy achieved? When was the initiation of flowering, bunch closure, and veraison?

• Keep track of sugar accumulation and harvest chemistry with at least Brix and pH. Yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN), titratable acidity (TA), and more data is helpful too, but will require a lab and more money.

What to Look For

The most important elements in evaluating home wines from your vineyard are:

• Competency: Make sure you have a basic education of wine evaluation and rely on better palates to help you if your skills are lacking. If you are a member of a home winemaking club, have the club taste your wine and use the feedback to make agreed-upon notes: Both positive and negative. Work on your own palate by making notes on every wine you taste (maybe not at parties or restaurants). Tasting wine is like playing the piano, you have to practice!

• Consistency: If your wines aren’t tasted and evaluated with great consistency every year, it will be difficult to use wonky notes/data to improve your vineyard outcomes. Also, tasting the wines as they age in bottle is important to this process as well. Keep checking in on your previous vintages and see what they have to say about your vineyard practices.

In Your Notes

So what type of tasting notes should be kept? Here are the bullets that I find most necessary:

• Color/clarity: Sparkling to cloudy/turbid, clear to golden in whites, light pink to opaque purple in reds and rosés.

• Aromas/faults: Use the wine aroma wheel to help guide you if descriptions are difficult.

• Flavor throughout the sip: First impressions as you put the wine in your mouth, mid-palate (how the wine sits in your mouth after a few seconds), and finish/persistence (how the wine tastes and lingers after swallowing).

• Overall impressions: Is the wine thin? Rich? Balanced? Is it yummy? Are you proud of it?

Diagnosing Vineyard Issues by Wine Evaluation

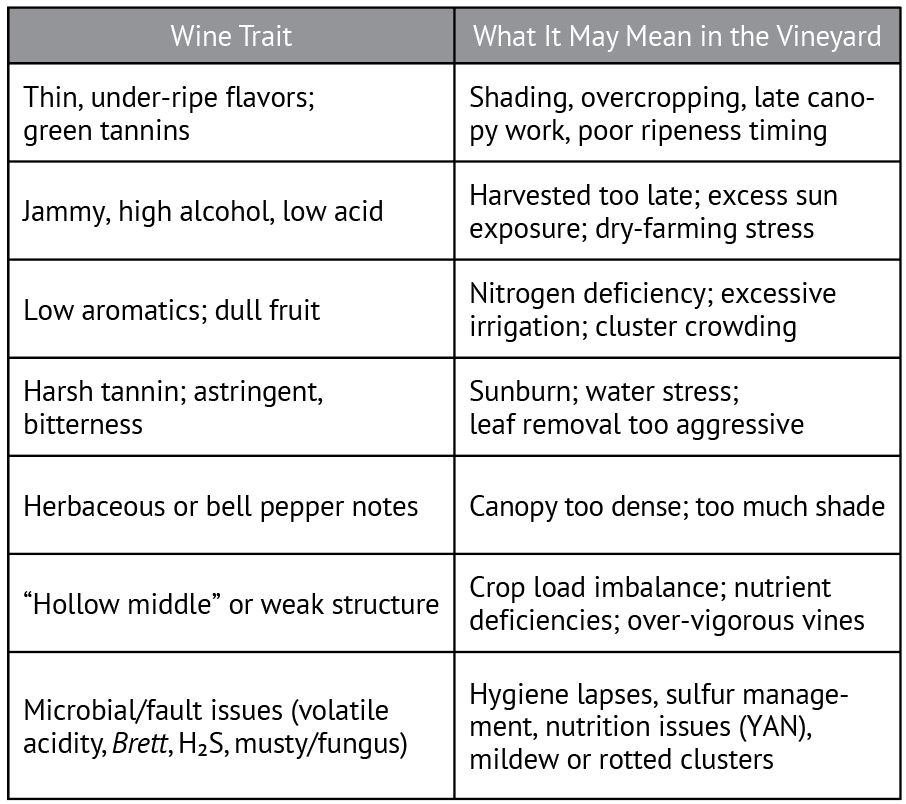

Here is a helpful chart for determining how your wine has “tells” for vineyard issues:

From the Glass to the Vineyard: Action Plans for Next Year

Understanding vineyard influence is distinct from winemaking faults. This can be a difficult distinction, and often takes a decade or more of notes, tasting, and research to differentiate. So what is the vineyard’s fault, and what is yours as the winemaker? I would argue it doesn’t matter, as human agency in the vineyard and the winery are connected, but for our purposes, we can strongly argue that vegetal/herbaceous qualities in the wine can be improved by canopy management, balance can be improved by vine-to-vine consistency of pruning, sun exposure, and consistent vigor across the vineyard.

Yeast selection, fermentation nutrition, temperature and kinetics, oak treatment, and additions have to be taken into account. However, harvest timing will have a huge impact on the outcome of the wine. The same vineyard makes drastically different wines at 21 °Brix as opposed to 25 °Brix. Same is true of acid/pH. 25 °Brix at 3.2 pH is a different vinous critter than 25 °Brix at 4.0 pH.

If your wines show musty/mildew faults, this may be due to mildewed/rotted clusters being included in fermentation. Improve or tweak your fungicide spray schedule. Also be more cautious at harvest about which clusters are used to make wine and which may be discarded.

Canopy Management Adjustments

Proper canopy management can be simplified by a few rules:

• 12–15 leaves per cluster, and at least 10% sun flecking on clusters at any time

• 1 leaf or less between sun and grape clusters

• All leaves plucked from the canopy’s interior so the vines are consistent in growth and have good air movement, spray penetration, and sun exposure.

If wine showed greenness, focus on opening up your canopy a bit more: Leaf pulling, shoot spacing, consistency of crop across the fruit zone. Be judicious on your increase of canopy gaps/open canopy so you don’t open the fruit up to sunburn damage. In areas with strong sun, consider leaving some leaves to shade the fruit from the hottest part of the day (10 a.m.–2 p.m.).

Alternatively, your clusters were harvested and fermented with sunburn and the wines show overt tannin/astringency, you may have gone overboard with your leaf pulling, and may need to leave some more leaves at fruit level to protect the developing clusters. Take notes on the quality of the fruit at harvest. What percent of the fruit had signs of sunburn? Was the fruit uniformly sun kissed? Were there dimpled or raisined clusters?

Vineyard Yield and Wine Quality

Balance in the vineyard is measured by vigor, and matching the amount of growth, canopy, and trellising to anticipated/historical growth expected. A vigorous vineyard can produce more fruit/wine that is still in balance, while a low-vigor vineyard should be expected to create less fruit.

Harness your vigor by properly matching trellising, management, pruning (more buds retained, more crop), and dropping green fruit at veraison to fine-tune crop yield. Overly cropped vines will tend to make thin wine. Properly cropped/balanced vines make wines that are rich and balanced. Take notes, tweak your techniques a bit, and see how the wine changes.

Irrigation Can Make a Difference

Vines need water all the way through harvest to achieve ripe flavors. Back when I started my vineyard management career (1994), the traditional wisdom was to “make the vines suffer for higher quality.” This “wisdom” has been mostly debunked. Vines need to photosynthesize (some green leaves) to develop phenolic ripeness in the fruit, which leads to flavorful, full-bodied wines. Driving the vines into dormancy by turning the water off will cause increased Brix vis a vis dehydration, which does not improve flavor/color. That said, some water stress at very specific moments of the year (like early berry development after flowering), can reduce berry size and increase skin-to-juice ratios.

Knowing your soil type (sand needs more water, clay less) and how your vines react to heat spikes, rainfall, and late-season (shutting down) will help you choose watering sets that keep the vines a bit green, and developing flavor, through harvest.

Know Your Soil Health and Vineyard Nutrient Status for Balance

Most home vineyards I help manage at Wes Hagen Consulting (weshagen.com) require little or no fertilizer to achieve good results. Never fertilize a vineyard that is healthy and happy, and never apply fertilizer without some data points/petiole samples. Petiole/leaf samples at bloom are the best way to get real-time data on vineyard nutrient status. I recommend my clients do a petiole/leaf sample at bloom at least every other year. These samples can be used to accurately fertilize/compost to improve specific deficits without causing problems like excess vigor or hindering ripening.

Before planting, and every five years, pull a soil sample from between 18–36 inches (45–90 cm) and send it to the lab for analysis. Soils change, and can be depleted by the vineyard, landscaping, weeds, and cover crop over time, so even if you had a sample taken years ago, that doesn’t mean the results hold true today.

Grape Sampling, Harvest Timing

Here’s a great example of a practice that is 100% grower-impacted. Deciding when to harvest is incredibly (and indelibly) important to final wine quality. Of course, weather often pushes our dates around, but I always prioritize wine quality over convenience. You only get one chance to pick great fruit, and make great wine, each year.

Most home winemakers I work with take fruit samples near harvest and get inaccurate results, usually testing their fruit as riper than it actually is. Whether you take berry samples or cluster samples, randomizing your selection standards is the only method for getting accurate results. If a human is asked to go get a “random” sample of ripening fruit, they will fail without a randomization protocol. Human vision is designed by evolution to prefer riper fruit (watch people in the produce section of a supermarket), so you have to find a way to randomize your samples. Use a random number like 3, 5, or 7, go that number of vines in, and that number of clusters in, take berries from different parts of the cluster each time, different sides (sun and shade) to get better accuracy for the timing of harvest.

Have a target ripeness in mind that has shown to make good wine from your vineyard. If the best wine you’ve made was pulled at 24 °Brix at 3.4 pH, use that as a target for making another great vintage. I know, weather and life may get in the way, but we can always dream . . .

While we are on the topic of timing your harvest, picking at night or in the cool morning air will always improve wine quality and reduce issues with spontaneous fermentations and volatile acidity.

Keep careful records of ripening curves, weather, seed browning, color development, and even consider doing tasting notes of the juice/fruit that you test.

Data To Track for the New Season

You have a notebook and you’ve tasted the most recent vintage wine and rated/ranked it for flavor, balance, faults, and development. Now you want to use the same notebook for tracking the next vintage, which should include:

• Vintage weather data and milestones

• Sensory and chemistry analysis of the wine

• Vineyard actions taken vs. results

• Plan for adjustments in the upcoming growing season

In Conclusion

Make Your Vineyard Into a Research Plot

Tweak each row with a little less or more leaf pulling or extra fungicide applications to see how many sprays are needed to keep clean fruit, pruning changes (leave a few less or more buds/canes on one row), add a little less or more fertilizer, even pick the vineyard in multiple passes and see how ripeness/hang time impact wine quality. Take good notes on all trials.

Taste, Adjust, Learn, Repeat

The process never ends, which is good news for people like me who want to taste wines constantly. The most important concept here is to record everything, and don’t forget to go back to previous notes for guidance.

Expand Your Tasting/Grower Circle Locally

Join local tasting groups, grower and winemaker clubs, internet groups, and educational sites. Utilize local and regional expertise to accelerate your education and wine quality.

The easiest part of this exercise is tasting and enjoying your wines on a regular basis. As your wines age, taste years side by side and ask yourself: What did nature do to this wine, and what did my decisions do? The more we ask ourselves these questions the more we realize that next year’s vintage begins with the glass of wine in your hand.