Making Country Wine from Berries

Summer is the time for berries, and that means berry wines. Loaded with flavor and unique aromas, chilled berry wines on warm summer afternoons lend credence to the lyrics, “It’s summertime, and the living is easy . . .”

Here are 15 summer berries suitable for wine that you can ferment as soon as the fruit is harvested to make delicious wines to enjoy next spring or summer.

Blackberry

Blackberry

One of the most common berries on earth, there are over 375 species of blackberry worldwide, found in temperate regions of every continent except Antarctica. The fruit are not true berries but aggregate berries composed of many drupelets. Blackberries occupy many species and subspecies of the genus Rubus. When picked, the torrus, or central pith from which the drupelets grow, accompanies the fruit. The fruit grows on thorny canes, which form thickets known as brambles. The fruit develop as green, then red, and usually ripen to a deep black. They are both juicy and sweet and their primary acid is malic, which diminishes as the fruit ripen.

Blueberry

There are dozens of natural species and varieties of blueberry in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa, but it is predominately a North American plant. It belongs to the genus Vaccinium, with at least 18 species referred to as blueberry. In the United States and Canada they range from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the Gulf Coast to the Hudson Bay. They normally grow as upright shrubs but certain species grow prostrate, varying in height from 3.5 inches (~9 cm) to 13 feet (~4 m). The fruit, a true berry, grows from green to red to black or powder blue when ripe and sport a flared crown opposite their stem. Fruit size varies from 1⁄5 to 3⁄4-inch in diameter, usually sweet and juicy. They are one of the few fruits that contain malic, citric and tartaric acids, but citric acid is predominant.

Boysenberry

The boysenberry is a hybrid between the loganberry, various blackberries and raspberries. As such, they do not grow wild except as rare escapees from cultivation. They exhibit a reddish-purple color, which changes to a deep maroon when heated.

Because their parentage is mixed, boysenberries vary in sweetness and tartness. The fruit is high in acid content, but less than the loganberry. Their natural sweetness is less than the blackberry and their tartness is less than the raspberry, which makes them taste sweeter than they really are. In wine, the berry flavor is subtler than wine from either raspberries or loganberries but more tart than wine from blackberries.

Currant

Currants belong to the genus Ribes, of which there are about 150 species. Some taxonomists place gooseberries in the same genus while others treat it separately as Grossularia. Red and black currants are native to northern Europe and Asia. Golden currants are native to North America. Currants come in black, red, white and golden (or yellow) and generally grow in trailing racemes on bushes 3 to 5 feet (1 to 1.5 m) high and wide with 5-lobed, sometimes palmate leaves. They are smallish translucent berries, 1⁄5- to 2⁄5-inch in diameter with several small seeds. Black currants have a tougher skin than others. Red currants are more tart. White currants are actually albino red currants but sweeter than the reds.

Dewberry

Dewberries include about 15 species of Rubus closely related to blackberries. They are small, trailing (rather than upright) brambles with aggregate berries reminiscent of the raspberry but usually purple to black instead of red. Wild dewberries tend to be smaller, more tart and less black than blackberries, but superior cultivars can be difficult to distinguish. Unlike blackberries, dewberries have separate male and female plants. The European dewberry grows more upright like other brambles, but is frequently restricted to coastal communities, especially sand dune systems. Its fruits are markedly more tart than blackberries even when fully ripe.

Gooseberry

Gooseberries are in a subspecies of genus Ribes, R. uva-crispa syn. R. grossularia. European gooseberries have spread throughout northern Europe, Asia and northwest Africa. American gooseberries are native to northeastern and north-central United States and adjacent parts of Canada, and California’s mountainous regions north into Canada. Gooseberries grow on spiny shrubs and species vary in color when ripe from pale purple, greenish-purple, dark green, dark purple, black to red. Their bushes are spiny, the fruit of some are spiny, and unlike currants they do not flower and fruit on racemes but short stems, either singularly or in pairs or threes. Most are sweet, flavorful and aromatic when ripe, but some are bitter or otherwise unpleasant. All gooseberries are acidic and astringent when unripe. Gooseberries also contain more seeds than currants.

Jostaberry

Seldom found in the wild, the jostaberry is a complex cross in the Ribes genus, involving three original species — the black currant (R. nigrum), the North American coastal black gooseberry (R. divaricatum), and the European gooseberry (R. uva-crispa). The plant is a thornless bush that grows to 6 feet (1.8 m) and has resistance to diseases that attack and kill the parent plants. The black berries, which look more like a gooseberry than anything else, are smaller than a gooseberry but larger than black currants. They flower early and the fruit persist through late summer if the birds allow it. Underripe berries are tart but can be cooked as gooseberries; ripe berries taste intermediate between a gooseberry and black currant, with the latter flavor developing as the berry ripens. They are good processed, cooked or as wine.

Juneberry

The Juneberry, also know as shadbush, shadwood, shadblow, serviceberry, sarvisberry, wild pear, chuckley pear, saskatoon, wild plum, or sugarplum is any of several related North American species. Juneberries are primarily northern to central tier natives, of multi-trunked small bush or tree in the genus Amelanchier. The fruit is a berry-like pome, red to purple to nearly black at maturity, 1⁄5- to 3⁄5-inch in diameter, grow in small clusters of 1 to 4 or racemes of 12 to 20 fruit and vary from bland to delectably sweet. Juneberry seeds are almond-shaped and relatively soft. While primarily a northern plant, an Amelanchier species is native to every state in the United States except Hawaii.

Loganberry

Loganberries are thought to be a chance Rubus cross between a blackberry and red raspberry. They look more like a raspberry but taste more like a blackberry. They develop large, light red berries that darken in redness when ripe and possess a unique, tart flavor that many people prefer over all other berries. They make a truly exceptional wine that must age considerably if dry, a lot less if sweet.

Oregon Grape

Oregon grape is the type species of 70 species of the genus Mahonia, closely related to Berberis. The genus is widely spread from Central to North America, eastern Asia to the Himalaya, but Oregon Grape is confined to the Pacific Northwest. The medium-size bushes (7 to 10 feet/2 to 3 m) have non-uniform shapes, bear leathery, spiny (holly-like) evergreen leaves which turn reddish-purple in winter. The flowers are in terminal clusters or racemes, as are the fruit. The fruit are bluish-black, globular as are grapes, 3⁄8- to rarely 3⁄4-inch in diameter, and sharply sour. They can, however, make a decent wine.

Raspberry

Raspberry is the plant and edible fruit of a multitude of plant species in the genus Rubus, most of which are in the subgenus Idaeobatus. Raspberries are perennial with woody stems forming loose brambles. Canes are arching but soon trail unless they are staked. The name refers to red raspberries unless a distinction is made to black, yellow or purple raspberries. Yellow raspberries are albino-like pale yellow variants. Purple raspberries are natural or induced hybrids of red and black raspberries.

Raspberries are aggregate berries and distinctive in that when picked the torrus, or central pith from which the drupelets grow, remains with the stem leaving a hollow fruit. Approximately 100 drupelets form each aggregate raspberry. Cultivars can produce berries up to 11⁄4-inch long while wild berries tend to be half that size. Their unique flavor easily transfers to a wine’s taste and aroma. Black raspberries possess a slightly subdued but nonetheless distinctive flavor.

Salmonberry

Salmonberries (Rubus spectabilis) are native to the Pacific coastal regions from northern California well into Alaska. A hardwood cane that tends to turn bushy, it can reach impressive heights of 10 to 12 feet (3 to 4 m), but usually tops out around 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 m). Its flowers are purple and its large aggregate fruit (3⁄5- to 4⁄5-inch long) resemble the raspberry in that the pithy torrus remains with the stem when ripe berries are picked, leaving a hollow berry. They ripen to a variety of dark yellow to orange to orangish-red. The palatability of the fruit depends on ripeness, soil and growing season, but most berries are good eaten raw and even better when processed into jelly, jam, cobblers, syrup or, of course, wine.

Tayberry

The tayberry is a cross between the blackberry (R. fruticosus) and red raspberry (R. idaeus) and is larger, sweeter and more aromatic than loganberries. Tayberries are cone-shaped, less acidic than loganberries, very large (11⁄2-inches long), and with a tart flavor. They retain their torrus when picked but are soft when ripe and cannot be machine harvested. They can be eaten raw, processed, baked, or made into wine.

Thimbleberry

Thimbleberries (R. parviflorus) are native to western and northern North America to the Great Lakes region and related to raspberries. Thornless, it forms dense shrubs up to 8 feet (~2 m) high with large (8-inch) palmate leaves and flowers (3⁄4- to 2.5-inches). The fruit are bright red and soft at maturity and smaller than raspberries (2⁄5-inch diameter). The berries can be sweetish tart to tart, eaten raw, processed, baked or made into wine.

Wineberry

The wineberry (R. phoenicolasius) is an Asian raspberry introduced to North America and Europe where it escaped cultivation and naturalized. It grows to a height of 9 feet (~3 m) and flowers on laterals on second-year wood. Flowers and fruit are on racemes and ripen unevenly to a dark orange to dark red. In size they are 2⁄5- to 1⁄2-inch in diameter, sweetish tart, with raspberry flavor. They may be used as raspberries.

Making the Wines

Making the Wines

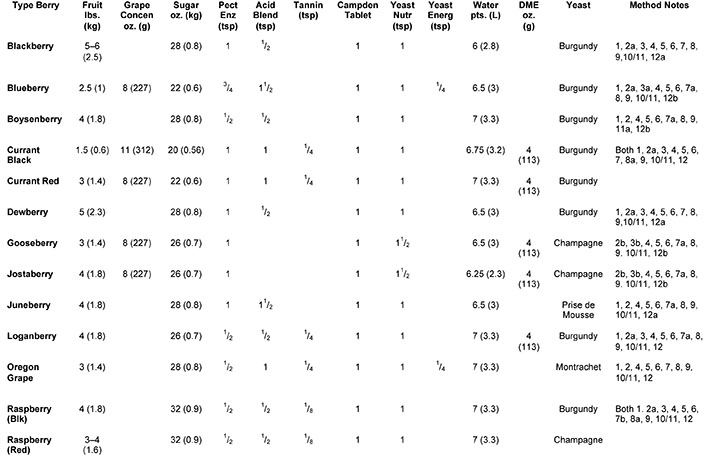

I have constructed a chart (see below) to consolidate all 15 recipes for making these berry wines, except that there are actually 17 — black and red currants are treated differently, as are black and red raspberries. All you have to do is follow a recipe’s guidelines and method, but first a word of advice: The recipes are just guidelines and if followed to the letter will make good wine unless the berries are underripe or inferior in taste. If you have the equipment, measure the specific gravity before adding sugar and acidity (as TA) before adding acid blend. This will enable you to adjust the ingredient measure to the actual must at hand.

Volume

You also need to know that all recipes make one US gallon (3.8 L) of finished wine, but initially the recipe will make more than a gallon. If you begin with a 4-liter secondary and rack to a 1-gallon (3.8-L) jug, the amount of volume lost to the lees will approximate the difference in volume between the two secondaries. If you do not have different size secondaries you can store the excess volume in the refrigerator or freezer until needed for topping up. At the middle to end of the process you will run out of excess to top up with, so use a compatible red, white or blush wine or just plain water.

Yeast

The yeast recommendations in the chart are generic. Burgundy refers to any of several strains isolated in Burgundy for red grapes regardless of name, brand or manufacturer. The same is true for Champagne, and most manufacturers supply a yeast that is Prise de Mousse, regardless of what they call it. Google can help if you get stuck. And, nothing here is written in stone. Use a yeast you know if that makes you comfortable.

Legend

In the chart, “Grape Concen” refers to grape concentrate, “Pect Enz” is pectic enzyme and so on. “DME” is dried malt extract, which adds body to an otherwise thin wine. Every local homebrew shop in the world carries it. Use DME according to the recipe’s measure and the manufacturer’s directions.

Method Notes

The method notes at the end of each recipe are listed in the order intended for the recipe. Only specific notes are selected for each recipe. The methods are listed beneath the chart.

Berry Harvesting Tips

Before harvesting summer berries, take some of these precautions to stay safe and make better wine.

Dress protectively: Most, but not all, berries grow among foliage sporting thorns. Long sleeve shirts are advisable when picking from brambles. Long sleeves also protect you from inadvertent skin contact with unseen nettles and poison ivy, oak or sumac that could cohabitate with your juicy prizes. Loose fitting denims and high-top boots offer protection from rare but potential encounters with poisonous snakes, or more commonly deer ticks. Rubber, nitrile or latex gloves protect your fingers from staining juices while still allowing you to feel the berries and exert just enough pull or twist to free them from their stems.

Wash and cull thoroughly: You will be amazed by how many unseen insects, tiny spiders and other unwanted guests will hitch a ride home with you among your berries. Flooding water into your bucket or a basin filled with berries will bring them to the surface. What you do with them after that is up to you. Washing also rids them of dust, bird droppings and other unwanteds. While washing the fruit, cull out any berries that are unripe, bird- or insect-damaged or any that are well past ripe and heading for decay or mummification.

Process immediately: If you cannot start making wine immediately, drain the berries thoroughly, allow to dry and refrigerate overnight or freeze them for later use.

Winemaking Method

1. Crush your fruit in a nylon straining bag in a primary fermenter

2. Pour cold water over the fruit 2a. Pour boiling water over fruit 2b. Boil water, stir in sugar, add fruit, and simmer for 20 minutes

3. Allow the must to cool to below 90 °F (32 °C) 3a. Allow the must to steep covered for two days 3b. Refers to 2b — pour hot into primary and allow to cool

4. Add all that apply: sugar, acid blend, tannin, pectic enzyme, yeast nutrient, yeast energizer, dried malt extract, according to manufacturer instructions; stir to dissolve; set aside covered 12 hours

5. Stir in a crushed Campden tablet or 1⁄16 teaspoon potassium metabisulfite and stir until dissolved; set aside covered 12 hours

6. Add the activated yeast as starter solution

7. Stir daily until specific gravity drops to 1.020 or below

7a. Stir daily for five to six days

7b. Stir daily for seven days

8. Press juice and discard pulp and seeds

8a. Drip drain the pulp (do not squeeze bag) for 30 minutes

9. Transfer liquid to secondary and attach airlock

10. Rack (top up and reattach airlock) every 30 days until clear and no sediments drop for 30 days, bottle for dry wine

11. Stabilize (1⁄2 teaspoon potassium sorbate and 1 crushed Campden tablet), sweeten to taste, reattach airlock, and wait 30 days to check against continued fermentation; bottle for off-dry to sweet wine

11a. Refrigerate wine until crystals precipitate, rack off crystals, then follow 11

12. Age 6 months

12a. Age 6–12 months

12b. Age 12 months