Making Sherry-Style Wines

Over the centuries, many styles of wines defined winemaking regions of the world. In Old World winemaking regions for example, Champagne, the sparkling wine, made the French town bearing the same name very famous, while Port wine is the gem of Oporto, Portugal.

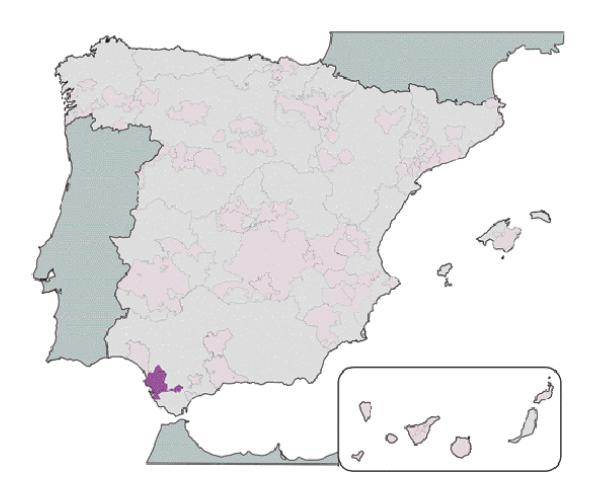

And so it is with Sherry, the quintessential wine indigenous to the Jerez region in coastal southwestern Spain. The word Sherry is the anglicization of the mispronunciation of Jerez; the French refer to it as Xérès.

Like Port, Sherry is a fortified wine but it is strictly made from white grape varieties and comes in several styles ranging from bone dry to cloyingly sweet depending on aging and sweetening regimens following fortification — the technique of adding a distilled spirit to arrest fermentation for increasing alcohol content and possibly residual sugar too.

But unlike Port winemaking, which relies on barrel- and bottle-aging regimens to create the many styles, Sherry winemaking makes use of flor yeast and a fractional blending system called a solera to create drier and lighter styles of Sherries known as fino. Those styles made without the use of flor yeast, but where the wines are allowed to oxidize in the solera system, are referred to as oloroso. Fino Sherries are considered more delicate and more complex and, hence, of higher quality than oloroso Sherries, which tend to be heavier and much sweeter.

Note: The common names “fino” and “oloroso” are used here to denote the general styles or categories of Sherry wines and to differentiate them from the use of “Fino” and “Oloroso,” which refer to those specific fino and oloroso styles of wines, respectively. Other specific styles within those categories are also spelled as proper nouns here.

Flor yeast is a film-forming surface yeast that blooms (or flowers, from the word flor) during the highly humid conditions of the region and which develops into a thick layer on the surface of the wine to protect it against oxidation while imparting characteristic organoleptic qualities. The solera system is an oak aging regimen involving racking a part volume of newer wine from barrels into barrels containing older wines. We’ll examine these two winemaking techniques in more details below.

Sherry Winemaking

It is often said that winemaking is part art and part science; however, Sherry-making requires a lot of experience and masterful art — it is certainly not trivial nor for the impatient type.

Palomino is the predominant (white) grape variety used in making all styles of Sherry. It is ideally characterized by low sugar and is surprisingly neutral flavored. Palomino’s organoleptic neutrality is actually desirable; flavors and aromas are to come from the flor yeast and solera system. Its lower acidity also requires acid addition in the form of tartaric acid.

Moscatel Gordo Blanco (also known as Muscat of Alexandria) and Pedro Ximénez (often shortened to PX) can also be used although the intensely sweet PX is most often used for blending to make a sweeter style Sherry. Pedro Ximénez is also used to make the dark, syrupy sweet wine of the same name when used as the base wine (instead of Palomino).

Grapes are harvested at around 20 °Brix, which yields just over 10% alcohol by volume (ABV). Similar to grape processing techniques used in modern-day white winemaking, grapes are destemmed and pressed without crushing (ideally) to minimize phenolic extraction, which could otherwise impart an undesirable harsh character. Only the press fraction extracted from a very light pressing, i.e. the free-run juice, is used for making the finest Sherry. The press fraction from heavier pressing, i.e. the press-run juice, is more tannic and goes into making a fuller-bodied Sherry where the tannins are tamed by the oxidation.

The free-run juice is left to settle and then separated by mechanical means from the heavy grape matter. Tartaric acid may be added if the total acidity is too low (or pH is too high). The juice is then inoculated with flor yeast to start the (anaerobic) fermentation process although this has been traditionally conducted using indigenous flor yeast well suited for the humid climate necessary for the yeast to bloom. Relying on indigenous yeast was tricky since flor yeast can only thrive in a very narrow alcohol range, between 14.5% and 16% ABV as some studies have shown for the required aerobic phase of fermentation.

There can be many species of flor yeast including Candida mycoderma, which winemakers will recognize as the culprit in surface yeast infections in poorly topped up carboys or barrels, as well as Pichia membrafaciens and several from the more familiar Saccharomyces genus. The key performance attribute of flor yeast is that, under aerobic conditions at the end of the alcoholic fermentation, when there is no more sugar to ferment, the yeast starts oxidizing ethanol into acetaldehyde (ethanal), which is easily identified as a nut-like smell in oxidized wines, and a whole host of by-products that contribute to the distinctive bouquet of Sherries.

Fermentation is conducted at relatively warmer temperatures than in white winemaking, up to 77 °F (25 °C), and in stainless steel tanks to avoid imparting barrel-fermented characteristics. Only later will the wine undergo aging in barrels. When the wine has reached dryness, it is racked and then fortified with a grape distillate to between 15.5% and 22% ABV and then aged for up to two years before entering the solera system, and then possibly sweetened based on the desired style. The most recent vintage wine to enter the solera is called the anãda.

Both fino and oloroso start off as dry wines. Those destined for fino styles are fortified to approximately 15% ABV, while those for oloroso styles are fortified to 18% ABV or more so as not to undergo the effects of flor yeast. Flor yeast becomes inhibited above 16% ABV; the wine is simply sweetened to make oloroso styles of wines.

As the flor yeast blooms and develops into a thick layer on the surface of the wine in partly (approximately 80%) filled barrels, which controls oxidation by scavenging oxygen, the biochemical changes and chemical reactions impart the characteristic nut-like aromas and flavors found in the drier and lighter fino sherries. The flor yeast also reduces acetic acid preventing the wine from turning to vinegar. When flor yeast is not able to bloom because of unfavorable conditions, the wine is allowed to oxidize under controlled conditions but without the effects of film-forming yeast, and processed into a fuller-bodied, sweeter oloroso style.

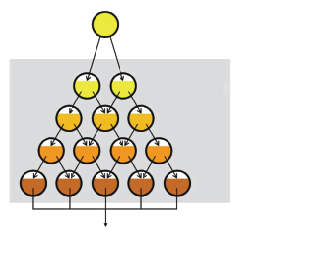

The solera system consists of 158-gallon (600-L) American oak casks, called butts, arranged in pyramid fashion usually stacked four or five butts high or higher depending on the style. The finest Sherries require longer aging and contain much older wines and therefore require much higher soleras. Butts in the top row, or criadera, contain a blend of newer wine including the anãda wine. As newer anãda wine enters the solera, wine in butts in the top criadera is partly racked into the lower criadera, and so forth until the wine is racked into butts in the bottom row, or suelo. And so butts in the suelo contain the oldest wine. Sherry then does not carry a vintage date as it may contain wine from a solera started 5 or many more years ago, possibly over 100 years ago. Some labels may state the year in which the solera was started to produce the Sherry.

During aging in butts under the effects of flor yeast, butts holding older wine at the bottom of the pyramid must be replenished successively with younger wines from above the pyramid to provide much-needed micro-nutrients for flor yeast development in older butts—this is the essence of the solera system, depicted in the figure below.

As wine progresses down the solera, it becomes progressively darker. When ready to bottle, approximately one-quarter to a third of the wine is drawn off from each butt from the suelo, and possibly suelos from other soleras, then blended, and the alcohol level is adjusted (if necessary). The wine is fined with egg white, isinglass or gelatin, filtered, cold stabilized, and then sterile (membrane) filtered for bottling. Butts above the suelo are then replenished to maintain the solera equilibrium.

Sherry Styles

As we have seen, there are two major types or categories of Sherry wines: fino and oloroso. Fino wines are considered of higher quality made from the best grapes and are most delicate in terms of structure and organoleptic complexity. Fino is a dry, light style Sherry with a paler color than oloroso, which is fuller bodied and sweeter; however, there can be style crossovers as bodegas can each create their own styles. But fino Sherries are defined by their origin of production whereas oloroso Sherries are classified according to quality.

Manzanilla is a fino Sherry, and the lightest and driest, produced in the town of Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Manzanilla Pasada is a Manzanilla that has undergone flor yeast aging.

Fino (with an uppercase F) is a fino Sherry produced in the town of Jerez de la Frontera. Amontillado, or more precisely Fino Amontillado, is a fino that has undergone flor yeast aging. True Amontillado, however, is made from either Manzanilla Pasada or Fino Amontillado that has been further aged in completely filled butts for added complexity and richness following the addition of grape distillate to approximately 17% ABV to inhibit further flor yeast activity. The alcohol level can progressively increase to 20%, albeit very slowly, as the water content in butts evaporates. Fino-style Sherries do not benefit from bottle aging and are meant to be consumed well within a year of leaving the solera system and into bottles.

Oloroso (with the uppercase O) is a fuller-bodied, richer style as it is allowed to age for very long periods of time — up to 30 years — under the influence of air in a solera system without the effects of flor yeast (it cannot develop given the higher alcohol content), which also increases progressively as water content evaporates. The extensive aging under oxidative conditions makes for a dark-colored wine with caramel and toffee aromas and flavors.

Pedro Ximénez (which is also the name of the grape variety) is a sweet oloroso made predominantly from Pedro Ximénez grapes.

Cream Sherry is an oloroso (from Palomino grapes) sweetened through the addition of Pedro Ximénez, which may contain some color wine added to get a more consistent color for the style. Pale Cream Sherry is a variation of Cream Sherry where color is removed or where Jerez (fino) Sherry is sweetened into oloroso.

Palo Cortado is an obscure Amontillado which has been aged extensively to exhibit the dry style of Amontillado but with the full-bodied character of a dry oloroso.

In summary, in order of increasing body and sweetness, the fino Sherries are:

Manzanilla, Fino, Amontillado and Palo Cortado. The Oloroso Sherries, in order of increasing body and sweetness, are: Oloroso, Cream, and Pedro Ximénez.

Making Sherry At Home

There are several ways of making Sherry-style wine at home from grapes or fresh juice, or from a kit; the latter is the most simple, foolproof method.

From grapes or fresh juice, choose a white variety harvested at a relatively low sugar content, around 20 °Brix, preferably Palomino, but Pinot Grigio or even Chenin Blanc will work well too, and decide what style of Sherry you want to make, i.e. Manzanilla, Fino, Amontillado, Oloroso, or Cream. Crush, or if you can, simply press grapes and transfer the juice to a carboy. Oak barrels are not recommended unless you intend to make Sherry every year using the same barrels; it would be almost impossible to eradicate the flor yeast from the barrels for use as a conventional aging barrel. Let settle for 24 hours and then rack to another carboy. Follow this step if using fresh juice. Add 100 mg/L of SO2 to keep lactic acid bacteria in check, which could otherwise impart undesirable flavors and aromas.

Inoculate with a suitable flor yeast, such as Red Star’s Flor Sherry, and ferment to dryness by maintaining the temperature around 77 °F (25 °C). Rack the wine into another carboy. larger than the first, or into two smaller carboys. The idea is to fill the carboys about three-quarters to let air interact with the flor yeast for the aerobic fermentation phase.

The wine will contain approximately 10% ABV at dryness. Based on the desired style, add a 70%-ABV grape distillate to obtain the desired alcohol level. For example, to bring 5 gallons (20 liters) of 10%-ABV wine to 15.5% for a Fino Amontillado style of Sherry, using the Pearson Square to make the calculations, you would need close to ½ gal (1.8 L) of a 70%-ABV grape distillate. Add the required amount of distillate to the carboy making sure it is only filled to about three-quarters. Use cotton — not a fermentation lock — to loosely plug the carboy opening, the idea being to permit the exchange of air in/out of the carboy.

For a fino style Sherry, let the flor yeast do its magic until the surface is completely covered. Let the wine age as desired, tasting it occasionally to assess progression. The temperature should be maintained at around 68 °F (20 °C) during flor yeast activity and aging process. Use a wine thief or a gravy baster to retrieve a small wine volume from under the surface film. To accelerate the “flavoring” effects of the flor yeast, agitate the flor yeast into suspension as the surface becomes covered.

When done, rack the wine to a new carboy. Here, you have several options depending on the desired style. You can bottle the wine for a fino style Sherry, and age it further for an Amontillado style, or age it further by letting it oxidize in a partially filled carboy, fortify further and sweeten for an oloroso style. The possibilities are limitless. Before bottling, taste and adjust the alcohol level if required, add sulfite to maintain 100 mg/L of free SO2, cold stabilize, fine lightly and filter.

An alternative to the oxidative process is to bake the wine. This method is hard to control in a home winemaking environment and may yield undesirable results, e.g. it may volatize desirable flavors and aromas, if the wine is excessively heated.

Drinking Sherry

Traditionally, Sherry was served by first withdrawing a small amount directly from casks using a venencia — a short cigar-like tube with a long handle — and held high above one or two copitas (glasses) for pouring and serving. A standard Institut National d’Appellation d’Origine (INAO) wine glass is the best and most common glass for enjoying Sherry.

Drier-style finos, i.e. Manzanilla, Fino and Amontillado, are best served chilled to allow their acidity to add some zip for a more tangy taste. The fuller-bodied Palo Cortado and olorosos are best served at a cool (cellar) temperature on their own as dessert. And contrary to popular belief owing to the higher alcohol levels found in these types of wines, a bottle of dry Sherry should be consumed within 24 hours — any longer and freshness disappears and the delicate aromas and flavors will quickly go rancid. The more robust, fuller-bodied styles can last several weeks, especially if refrigerated, owing to their higher alcohol and sugar contents (high sugar content acts as a preservative) and that the wines have already undergone extensive oxidation.