The Importance of Temperature Control in Winemaking

Maintaining the temperature of your wine — from the moment it arrives in your door until the moment the wine bottle gets popped — plays a huge role in the finished product. Mainly winemakers will talk about the temperature during active fermentation or during long-term aging, but there are other times when temperature control can be highly beneficial. Let’s take a quick peek to see a few whys, whens, and hows to take control of this facet in your winery.

Ways To Gain Control

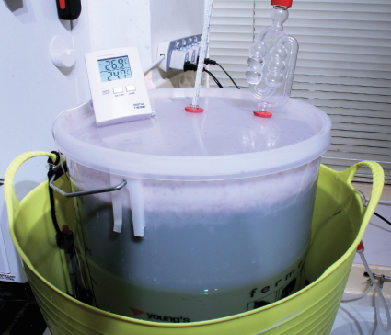

There are plenty of options winemakers utilize to control temperature of their grapes, must/juice, fermentations, and finally wine: Nighttime harvesting, dry ice, old refrigerators, heating pads, or glycol-jacketed fermenters . . . these are just a few examples. How you go about controlling temperature first off depends a lot on your budget. Frozen plastic milk jugs cost basically nothing, but the level of precision is low and the time spent monitoring temperature is high. Buying your own glycol system means initial costs are high, but then you are rewarded with a high level of precision and low time and maintenance costs. Middle of the road you’ll find that buying an independent temperature control unit, like a Johnson Controller or UNISTAT controller, that manipulates a refrigerator and/or heat pad, may be the perfect solution for you. Many temperature control units are dual stage, which implies they can be set to both heat and cool, so it can control both a fridge and a heat pad at once. Single stage means they can only perform one of those tasks — you must purchase them separately for heating or cooling.

Grapes-into-Wine Phase

Right off the bat, many winemakers who harvest their own grapes like to keep their grapes cool at harvest, so many will pick their grapes in the overnight hours. This allows for better initial control over their fermentation once the grapes are crushed. An optional technique called cold-soaking, where red grapes are crushed then kept cold for several days prior to active fermentation, may be the next place for temperature control. Dry ice, frozen milk jugs, refrigerators, walk-in coolers, or glycol systems are all ways winemakers will keep the grapes between 40–50 °F (5–10 °C) during a cold soak.

For most wines, active fermentation will be the initial place where temperature control is desired. Depending on your goals with the wine you may want to either heat the fermentation process up or cool the fermentation down . . . depending on batch size, ambient room temperature, wine type, and yeast selection. Again, you need to figure out what you want out of the yeast and understand their interactions with the juice. A warmer fermentation is often desired for more robust red wines. This enhances extraction of the phenolic compounds from grape skins (if your wine is on grape skins), which can greatly affect both the color and tannin composition of the wine. But too warm of fermentation temperature, starting around 86 °F (30 °C), and the yeast may start to throw off undesirable sulfur-derived compounds like hydrogen sulfide. Kit and juice red wines are optimally fermented somewhere between 68–86 °F (20–30 °C). Whole grape red winemakers will want warmer (75–86 °F/24–30 °C) ferments for better color extraction. Regular punching down of the cap for this same group will help control the temperature. Punching down allows heat to be redistributed throughout the fermentation and some heat to escape. But if a more aromatic, delicate red wine is your goal, fermenting on the cooler end of these temperature ranges would be preferred.

For white, rosé, and fruit wines, fermentations are generally recommended to be kept below 60 °F (15 °C). A cool fermentation with these styles of wines will better retain the delicate aromatics, like the thiols with aromas of tropical fruit, that give these wines much of their character . . . the fermentation bouquet. A slow and steady fermentation is the goal with these styles of wines.

After Fermentation Temperature Control

Once fermentation is complete, some red winemakers might provide more time for the juice and grape skins to interact. This is known as an extended maceration and is best done at slightly chilled temperatures. This process has been noted to lead to a “softer tannin profile” but is not recommended for beginners since this can lead to unnecessary oxidation and bitterness.

Secondary fermentation, known as malolactic fermentation (MLF), is often best done at elevated temperatures. This process is kicked off by introducing a lactic acid bacteria, inoculated near the end of primary fermentation and allowed to metabolize the malic acid in wine, converting it to lactic acid. Maintaining temperatures between 68 to 75 °F (20 to 24 °C) is usually ideal for MLF.

Cold stabilization is the next point in a wine’s life that temperature control may be warranted. Tartaric acid can become supersaturated in wines when cooled and tartaric crystals can form. They look like broken glass. By cold stabilizing a wine, the excess tartaric acid is removed prior to bottling, since many folks don’t like to see what looks like broken glass in their bottle of wine (don’t worry, it won’t hurt you though). Bringing your wine down to right around 32 °F (0 °C) for 36–48 hours (or longer) is all that is needed to cold stabilize a wine. One problem with cold stabilizing wine though is suck back. Be sure fermenters are topped off and a solid bung is in place prior to starting to cool the wine . . . you don’t want oxygen sucked into the fermenter.

Once your wine is bottled, a cool cellar is perfect to store your wine. If you don’t have the luxury of a cool cellar, trying to keep the wine at around 50–60 °F (10–16 °C) would be ideal. No matter what, be sure to keep out of direct sunlight.