Grapevine Diseases: Vineyard Rx

One of the trickiest parts of being a good viticulturist is learning to deal with grapevine diseases. The literature on the subject is exhaustive in its breadth and complexity — and exhausting to read and comprehend. How does one recognize and implement a plan to stop an emerging problem in the backyard vineyard?

Properly planted and maintained, most vineyards will produce good fruit for decades without any problems from disease. Keeping the vineyard healthy and watered, with a good balance of nutrition and hands-on manicuring, should help your vineyard resist most pests and grapevine pathogens. In other words, don’t let this article convince you that diseases will descend on your backyard vineyard like a yearly plague. Also realize that you have a distinct advantage over commercial winegrape farmers. If you have a problem with a few diseased vines or mildew-infested clusters in your vineyard, you can diagnose the problem quickly, remove a few vines or clusters if necessary and replant easily. Many diseases in commercial vineyards go unnoticed for years because the vineyards are so large that a few vines with leafroll virus or Pierce’s disease go unnoticed and untreated. The same is true with mildew — often times chemical solutions are necessary because the vineyard manager finds mildew after it has established itself. But in a backyard vineyard you have the benefit of observing each vine at least every week. Your vineyard is small and your farming is nimble. You can tailor a fertilization program to give the vines excellent natural resistance to disease pressure. You can also speak with local viticulturists about disease pressure in your own region.

The scope of this article is limited to major diseases. The problems that might occur in your backyard are well-known to other grape growers in your region and once again I implore you to use the winegrape farmers in your neighborhood as a valuable (and bribe-able) resource. Another advantage of owning a small backyard vineyard is the fact that — if worse really comes to worse — you can replant fairly inexpensively and only lose a few years’ fruit instead of having to declare bankruptcy and deal with the massive replanting costs of a commercial vineyard operation.

Healthy and balanced vines

I prefer to take a holistic view of vineyard health. Looking at the vineyard as a whole, it is vital to recognize that soil health, environment, weather, vine vigor, farming practices, varietals planted, root health, fertilization and pest and disease pressure all have a profound impact on the overall health of your vineyard. Before delving into the issues of mildew, rot and other diseases, let’s take a moment to discuss vineyard health and how it can help stave off pest and disease pressure.

A young man or woman who exercises, eats a healthy diet and is generally happy in life is much less likely to come down with a disease than an obese, lazy, pack-a-day smoking couch potato. Environment is certainly a factor but, as with a person, the health of a vine can determine whether a pathogen will take hold or move off in search of an easier host. Nature abhors the weak and disease will always look for the path of least resistance. Maintaining a vital, healthy vineyard environment will help your vines remain healthy. Strong vines will be increasingly resistant to diseases and pests. Using organic compost and fertilizers — such as fish emulsion, bat guano, kelp extract and the like — may be a great way to build up your vineyard’s natural resistance.

Many viticulturists believe organic fertilizers that increase the biological activity of the soil do wonders for a vine’s ability to resist disease. There are gaps in our understanding of how plants live and thrive, but I suspect those farmers that feed the soil as well as the plant are onto something. It’s obvious that a vineyard with plenty of insect species will be less susceptible to a single insect pest because all of the insects are so busy eating one another that it’s difficult for a single species to take over. Healthy vines have the ability to protect themselves and are less reliant on chemical controls. Keep this in mind as you read on. Make wise and informed decisions about how you plan to control mildew, rot and disease pressure in your own vineyard.

Diseases to consider

Powdery mildew

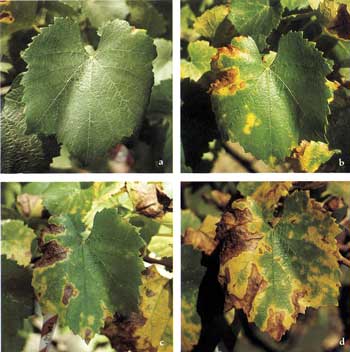

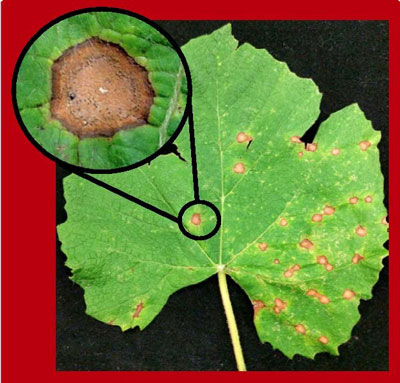

With no control (fungicide applications), powdery mildew is the one fungal disease you can expect to appear on your vines. The mildew appears as powdery white or grey mildew on the bottom of leaves or on the clusters. Often a mildew infection will start where two clusters are touching, or on clusters deep within a vigorous portion of the canopy. This is another reason to do a little leaf-plucking before applying sulfur, to make sure the material reaches the interior of the canopy for effective control of mildew. Grapevines in almost every region of the country need sulfur applications as soon as shoots reach about three inches of growth on average. Sometimes sulfur is coupled with copper, although there is evidence that copper can build up in the soil and is not recommended for all vineyards. Keep applying a fungicide such as sulfur every week to two weeks to keep the vines mildew-free from spring through the point that the grapes have accumulated sugar around 12–15 percent. Once the grapes hit around 15 percent sugar content, powdery mildew will not be able to continue its growth cycle. Also, be careful in applying sulfur after grape softening, as the sulfur may end up in your wine.

Temperature and humidity play a major role in mildew development as well. The fungus grows best in conditions of high humidity between 70–86 °F (21–30 °C). The optimal temperature for mildew development is 77 °F (25 °C). Temperatures above 95 °F (35 °C) will kill mildew colonies, and if the temperatures in your vineyard exceed 95 °F (35 °C) for more than 12 hours, expect that the mildew has been destroyed. Mildew lives in protected “pockets” on the dormant vines during winter, so don’t assume that winter has killed all of the mildew in your vineyard come spring.

In the spring, overwintered spores of powdery mildew are moved by wind and rainfall to other grapevines, and the cycle of growth and movement through the vineyard starts again. Early season control is vital. You may think your vines are clean, but there will always be some spores floating around. The key is to keep populations down throughout the entire year. Waiting to see mildew on the vines before spraying will lead to disastrous results.

Powdery mildew control

Start applying fungicide (usually sulfur) on a regular schedule, and watch the bottoms of the leaves carefully for signs of mildew infection. Most viticulturists apply sulfur to their vines every week to two weeks, depending on the temperature. Reapply after rains. Sulfur can burn vines if it is applied when temperatures are near 100 °F (38 °C), so try to time applications during warm, but not hot weather. Local conditions vary widely, and applications in some regions need to be every week, while some locations need sulfur as little as once a month. Learn what a mildew infection looks like and be careful to inspect your vines on a regular basis. A good hand-held magnifying glass will help you see the developing “powdery”or “downy” mildew colonies on the underside of young, soft leaf and shoot tissue. Remember that if your grape clusters are hidden in a shaded canopy, it will be difficult to get fungicide coverage on the fruit. Most of the spray ends up on the outer leaves, and the mildew pressure will be very high within the humid, warm environment of the inner canopy. Pull some leaves to open up the canopy, but don’t expose the fruit to the extent to which it will burn or raisin. You may also want to grow a variety that is less susceptible to powdery mildew, such as Petite Sirah, Zinfandel, Semillon, White Riesling, or natives or hybrids that are recommended by a good, local nursery for local conditions.

Bunch rot

Bunch rot, unlike powdery mildew infections, is more common at the end of the season. This is when the grapes are ripening, the weather is warm and conditions are correct for the Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium or Aspergillus to begin growing on soft fruit. Bunch rot usually appears initially as a discoloration of the grapes, and is most obvious on white varieties. Established bunch rot will start to give a fuzzy grey or blue appearance as the fungus begins to permeate the grape skin. Once the fungus has established itself on the fruit, the grape skin is usually broken by an enzymatic reaction to the fungus, and then other fungi and bacteria make their way into the grapes and wreak havoc. The vinegary smell of bunch rot is not actually caused by the fungus, but instead by the Acetobacter that is able to enter the berries that have been damaged by fungus. Acetobacter is the same bacteria that turns wine into acetic acid (or vinegar). The key here is to keep the fungus off the clusters, and apply controls in a timely manner to keep pressure down in the vineyard. For these fungi to grow, they require water and sugar. The sugar will be present if water sits on the skin of a ripe grape for more than two hours. It has been proven that the grape skin does not have to be broken for sugar to be present. So humidity (whether present from rain, dew, fog or irrigation) is a major factor in fungal growth. Optimal temperature for Botrytis fungal growth is 72° F (22 °C). High temperatures (above 90 °F/32 °C) will slow or stop fungal growth, but the fungus can grow slowly at low temperatures, even as low as 34 °F (1.1 °C). Even though the problem of bunch rot appears when the fruit is ripe, the fungus will grow and spread on succulent leaf and shoot tissue. If you have problems with bunch rot, using control in the early part of the season will help greatly later on.

Fungus or rot can actually kill young growing shoot tips, so keeping the rot controlled early on the vine will keep the vine healthy at the beginning of the season, and limit spores that are able to attack ripe fruit later on. Be wary! Under perfect conditions, Botrytis can infect a grape, destroy it, and produce further spores — all in less than 72 hours. Once rot sets into a cluster of ripening grapes, a host of other microorganisms will move in as well. The aromas of the rapidly decaying cluster will bring in Drosophila (fruit flies), which will hasten the decay of the fruit and increase the intensity of the Acetobacter infection and the vinegary odor. Once rot has set into your vineyard, there’s really little you can do. Try more early-season control in subsequent vintages. The less rot that is present on the vines, the less problems you will have as the fruit matures and becomes susceptible.

Bunch rot control

Try to keep your canopy open by pulling a judicious amount of leaves so that sunlight and wind can keep your fruit from living in a humid environment that is susceptible to heavy mildew and rot infections. It should be emphasized that leaf removal has been proven more effective than most chemicals in controlling bunch rot. So do your best to remove some leaves from around the clusters after bloom to help air circulation and reduce humidity in the canopy. Again, learn how many leaves can be removed without threatening the fruit with sunburn. Make sure to remove all clusters from the vine during harvest, even the ugly ones. “Mummy clusters,” unharvested clusters that were left on the vine all winter, will provide a source of spores once the spring weather reactivates them. Sanitation, a good spray program and careful cultural practices such as lateral shoot and leaf removal will help make the fruiting zone of your vines less amenable to rot and mildew.

Choosing varieties that have a resistance to rot will be helpful as well, especially if you live in an area that has strong rot pressure. Check with your local nursery for a good variety to grow. If you know that pressure is high (and you can grow vinifera), think about vinifera varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, or Muscat.

As far as fungicide applications go, check with your local nursery for the most efficient materials allowable for home use. The traditional material used is copper in a liquid form, and mixing a sulfur and copper spray (Bordeaux mixture) for the first three or four spring fungicide applications on your vines may be all the control you need. It is also recommended to add an application immediately after bloom, or when the fruit has set on the vines, and after heavy rains where water may hasten the development of early rot.

If some rot does appear on your ripe clusters, remove the affected clusters immediately. Being careful not to apply too much water or nitrogen fertilizer to your vines will help control bunch rot as well. Loose clusters — clusters in which the grapes are not jammed together on the stem — will allow irrigation water or rainfall to completely evaporate on the cluster, allow for air and sun exposure and keep the cluster from rotting as a result of trapping water and fungus in small, tight spaces between grapes. In general, less water and less nitrogen will result in loose clusters that are less susceptible to rot.

Conclusion

When it comes to grapevine diseases, powdery mildew and bunch rot are like the flu and the common cold: plan on dealing with them on a yearly basis. Rot and mildew will be something you need to think about at least three to four times a month in spring. Apply sulfur (or a sulfur-copper mixture) to the vines to keep the mildew and rot from spreading to the point where it threatens your crop. You will never completely win the war against fungus, but if you can control the rapid reproduction so it never appears to the naked eye, you will have done well.