In the last issue of WineMaker we concerned ourselves with the “common” diseases of backyard viticulture. As the flu and common cold attack the human body, powdery mildew and rot attack vineyards. As we discussed in the previous article, vigilant prevention and careful canopy management are vital to keeping your vines free from mildew and botrytis. Well-timed applications of sulfur, or a mixture of sulfur and copper, can do wonders to alleviate the potential damage of mildew and rot.

The diseases covered in this article will be more difficult to control and recognize. Many can be misdiagnosed and mistreated — so examine with a critical eye, lest you make hasty decisions. This article is not intended to teach everyone all there is to know about spotting a disease, diagnosing it, and solving the problem. Instead, I hope this will serve as a short primer, describing a few rare diseases that show up in vineyards. Also, this article should get you some of the necessary tools for spotting a problem, and finding a professional to confirm your suspicion. This professional should ultimately help you find a permanent solution. The best way to become familiar with these diseases is to actually see them in the field (or on the vine). Make it a point to observe a professional viticulturist in the process of diagnosing the problem, and participating in the course of treatment. Volunteering to help a local viticulturist walk his or her fields is a very insightful experience.

Without the benefit of a personal “vineyard disease tour,” I hope to supplement the readership’s knowledge with a description of some diseases and their basic effects on vines. The photographs throughout the next few pages should help you visualize the common symptoms. Again, I’d like to make it clear that treating a potential vineyard disease after reading a descriptive article on the subject is not a recommended practice.

Paying a university-trained vineyardist to assess your vines will almost always save you time, labor, and money, even if your vineyard is believed to be disease- and pest-free. With that in mind, let’s take a look at some of the diseases that can infect a vineyard. I have chosen the following group of diseases because they are generally the most common, virulent, and easy to diagnose from photographs. This is certainly not a complete list of diseases. A more complete list, with photographs, that no viticulturist should be without, can be found in the UC Davis “bible.” This is “Grape Pest Management,” a textbook compiled by the University of California at Davis in 1992.

Insect-Borne Diseases

Insect-borne diseases are actually fairly easy to understand. Pierce’s disease, for instance, is caused by a bug infiltrating a vineyard and spreading disease from vine to vine during feeding. A leafhopper, snail, or wasp can contaminate a plant while feeding directly on the vine’s fruit or leaf tissue. In the case of the mealybug, the insect can destroy the sanitation of the fruit by depositing residue or excrement.

There are two common options for treatment that viticulturists regularly use. The first is the best solution to any problem — prevention. Keep the pests out of your vineyard to begin with using traps, barriers such as a mesh fence, or chemical control agents (such as insecticides, oils or soaps).

The second option is based on organic and biodynamic methods. This treatment is a bit more involved, and arguably more risky. Planting cover-crops and allowing for a great deal of biological diversity in your backyard vineyard will attract a number of hungry insects. Those insects, it is believed, will be in a constant battle of eat-or-be-eaten with other insects, and (if the theory holds true) will keep any single insect species from “taking over” a vineyard. My suggestion is that you focus your attention on creating insect diversity in the vineyard, and if that doesn’t work, spray the hell out of those buggers. Remember that spraying will also destroy beneficial insects, which I like to avoid unless dire circumstances prevail. But, when things get dire, I suggest doing what is necessary (and what technology allows): Destroy the pests and make some wine.

Pierce’s disease: Pierce’s disease is named after N.B Pierce, who studied the bacterial disease in grapevines as it decimated much of the California grape industry in the first half of the twentieth century. The good news is that the insects that carry Xylella fastidiosa (and the bacterium itself) cannot survive the cold winters of the Midwest and northern states. The disease, therefore, is only prevalent in areas with mild winters, along the southern portion of the country from Florida to California. Pierce’s disease, or “PD,” is the greatest threat to vinifera (grapes of European variety) in the southern regions of America.

The disease is most commonly spread by small insects known as sharpshooters. The new “superbug” that threatens California viticulture is the glassy-winged sharpshooter (GWSS), which can fly three times as high as the more common blue-green sharpshooter. In general, the blue-green sharpshooter cannot fly over six feet, but the GWSS can fly as high as twenty feet with little problem.

All sharpshooters spread PD the same way. There are “host” plants that can keep the PD bacteria alive. These include blackberry, willow, coyote bush, elderberry and others. A sharpshooter feeds on these “host” plants, gets the PD bacteria into its mouthparts, and then injects those infected mouthparts into the grapevine’s tender tissues to feed (suck xylem fluid). The populations of sharpshooters grow quickly with the unlimited food source of a vineyard, and hop from vine to vine, spreading the bacterium. Often, as the rest of the landscape browns in summer, irrigated vineyards stay green. This makes them an obvious target for sharpshooters, who survive by consuming massive quantities of plant fluid. Sharpshooters like to live in wet areas near rivers and in ornamental landscapes (those that are irrigated). It is common to see the symptoms of PD infecting the edges of a vineyard that abuts a riparian habitat (a river).

The PD bacteria clog the flow of liquids within the grapevine, and can eventually kill it. The progression of the disease is fairly slow, often taking a few years to render the vine useless. Leaves take on a scorched, dry appearance and will appear uneven and stunted in sections. Late in the season, you may see leaf blades falling off the petioles. (The leaf stems remain on the vines without the leaf.)

The easiest symptom to recognize may be the uneven ripening of the wood — islands of brown hardened cane wood surrounded by green unripened wood. Like most bacteria, PD prefers warm climates, and the progression of the disease will be hastened by warm weather. Sharpshooters will also breed faster in warm weather, increasing populations and the speed in which they can transmit the disease. Besides some experimental injections of antibiotics with surgical screws, there presently is no cure for Pierce’s disease. Replanting in an area that is infested with sharpshooters and host plants may not be wise either. Unless you are comfortable with replanting every five years, it is generally suggested that Vitis vinifera vineyards are not viable in areas with large populations of PD-bearing insects.

Temecula, California has done an admirable job as an industry to stay alive in the midst of a serious sharpshooter infestation. Viticulturists there use a combination of strong spray programs and plant citrus fruits, the favored host of the GWSS, at the perimeter of their vines to attract the insects. In the mornings, when the populations of insects are highest, vineyardists spray the citrus trees.

In general though, fighting Pierce’s disease (if it is prevalent in your locale) in a Vitis vinifera vineyard is a fight you are likely to lose. It should be stressed that there are hybrid varieties of grapevines that are resistant to Pierce’s disease. If you live in a PD hot spot, check with a knowledgeable grapevine nursery and discuss your options for growing a resistant type of hybrid grapevine for wine production.

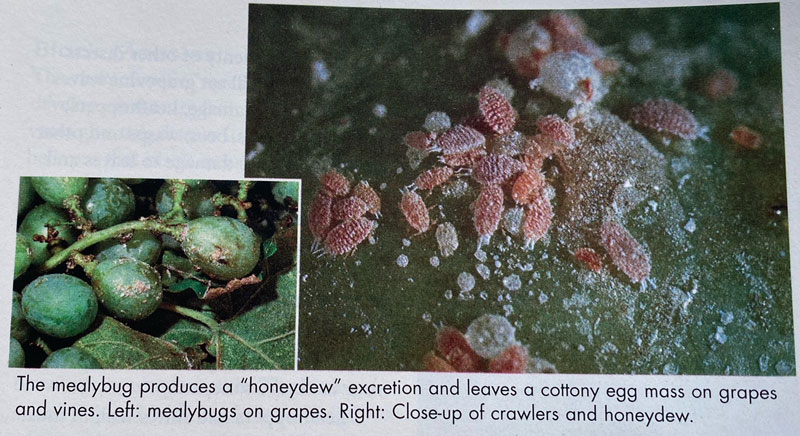

Vine mealybug: The vine mealybug produces a “honeydew” excretion and leaves a cottony egg mass on grapes and vine trunks or cordons, making them less attractive for winemaking. The signs that could suggest a mealybug infection are many and include: an increase in ant activity, a visual confirmation of mealybugs on the vines, white spots of honeydew, cottony “ovisacs,” or the characteristic black, sooty mold that will begin to grow on the honeydew. If you are seeing honeydew from vine mealybugs on more than 2% of your fruit, you should consider some kind of control program to reduce populations early in the growing season. California is seeing an increase in the population of these pests in recent years, and has been pouring money into research. However, because the mealybug seems to be an isolated problem, I won’t go into too much detail here.

Mealybugs can be controlled with chemical sprays such as “Applaud” which use a nicotine-like compound. There is also a newly available pheremone that is being used to cause mating disruption. When sprayed, the males can’t find the females, because the hormone smell is everywhere in the vineyard, and the mating of the animals is hindered.

As noted earlier, vineyards containing mealybugs can see marked increases of ants, including fire ants. These ants protect mealybugs from their natural enemies in exchange for honeydew. The best way for home gardeners or commercial growers to reduce mealybug numbers is to rid the area of ants. This can be done with baits, so the vines do not have to be sprayed. In a home vineyard, one bait station per vine (if mealybugs are present) would probably do the trick. Commercially, the recommendation is a scoop of bait per vine.

Leafhoppers, mites, and other insect pests: There are plenty of other insects and pests that will eat grapevine leaves and cause vine damage. Leafhoppers, mites, snails, ants, bees, wasps and other species can cause damage to leaves and ripening fruit. If your vines are being eaten by insects, do your best to control the populations early in the season. Once the vines are inundated by insect pests, control will be more difficult. You may want to use some sticky traps in the spring to monitor the insect species in your backyard vineyard.

Leafhoppers and mites will, in most parts of the U.S. where grapes are grown, be your biggest enemy as far as insects are concerned. Low populations (a number that does not result in your vines being eaten alive) will not threaten your vines or crop. If you see threatening numbers of leafhoppers or notice mite damage on your vines, try spraying a common insecticidal soap or oil to the vines. As always with insecticides, make sure to wait a week to 10 days after a sulfur application to make sure you do not disrupt the efficacy of your mildew-control program.

Fungal diseases

Fungal diseases are commonly spread through the wounds made on the vines during the process of pruning. If you are concerned about fungal diseases, or live in an area where rain is common at pruning time, you may want to ask your local viticulturist where you can procure some “pruning paint” to sanitize the wounds. This will minimize the risk of fungi entering the vines through wounds.

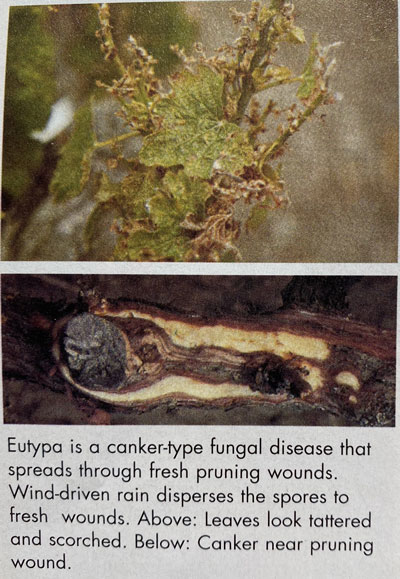

Eutypa dieback: Eutypa is a canker-type fungal disease that spreads through fresh pruning wounds. Rain is usually the culprit — spreading the spores of the fungus by splashing them from vine to vine, where they enter the vine through the pruning cuts. Symptoms usually appear as cankers (which look like darkened, dead wood that surrounds an old pruning wound) on the spur nearest the initial infection, and moves through the vine until an entire cordon arm or trunk is infected. The canker also spreads within the vine’s woody tissues. If you cut through an infected vine’s trunk or cordon arm, you will notice that only a small strip of live vine is present inside.

There are a few cultural practices that will reduce the chance of your vines becoming infected with Eutypa. Try not to prune when rainfall is expected. This is easier said than done, as pruning is often done in the winter, when rain is common. If possible, make pruning cuts in dry weather, and paint the wounds with pruning wound compound, such as “benomyl paint.” Of course, most home vineyardists won’t have access to benomyl paint, so it is suggested that you treat pruning wounds with a quick spray of Lysol or a paste of laundry detergent, being careful not to touch the dormant buds with these materials.

If you notice that your vines are developing the characteristic “deadwood” Eutypa cankers around old pruning wounds, it’s time to break out the saw and do some vine surgery. The key is to remove only the affected wood, and to stop where you hit healthy tissue (that is not dark and “dead looking”). If the vine has been infected to the point where there is no healthy wood left above the head, you can cut the vine back to a short trunk, and train a sucker from near the bottom of the vine as the new trunk.

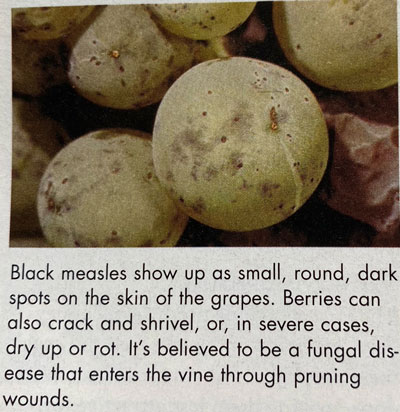

Black measles: The characteristic “measle” spots that develop on mature fruit of the infected vines give this disease its name. It is believed that black measles is a fungal disease that enters a vine through pruning wounds, so the same type of precautions used for Eutypa should be helpful in preventing black measles. When infected, the maturing grapes on a vine will show a characteristic dark spotting, each spot surrounded by a brownish or purplish ring.

The leaves of a vine infected with black measles also take on a very noticeable scorched pattern, which is usually most evident in July and August. Treatment is difficult and fairly dangerous. Reports indicate that treating pruning wounds with sodium arsenite can provide control in an already infected plant, but it is a dangerous chemical and may also leave residue that can affect wine quality and safety. It is strongly suggested that this chemical be avoided. If your vines become infected with black measles, remove the affected vines and replant.

Viral diseases

One amazing aspect of the grapevine is the ease with which a vine can be propagated. There aren’t many plants that you can cut during dormancy, shove a cutting in the soil, and have a decent chance of it growing into a new vine. The problem with grapevine cultivation is that it is so easy, and that the genetic “code” of the mother vine is replicated exactly in the new plant propagated. That means that any virus contained within the “mother plant” will also be in the propagated plant. Many grapevine nurseries are not as careful as they should be in locating “certified” or “clean” wood for creating new grapevines. A virus in grapevines is generally a nursery issue. (Note: Fanleaf degeneration should be considered an exception to this rule, because nematodes spread the disease between infected and unaffected vines alike.)

If you buy “certified” grapevine materials from a well-respected nursery, you should have little or no troubles from virus during the life of your vineyard. I cannot stress how important it is to buy clean material. The cost of clean materials is inconsequential next to the cost of having to rip out and replant a virused vineyard. I will also mention in passing that there are those viticulturists and winemakers that believe a “little virus” in the vineyard (whatever that means) may slow vigor and result in a smaller crop with more varietal intensity. There are plenty of ways to slow vigor and thin the crop to a balanced level without having to rely on a virus. If a virused vineyard is still attractive to you after reading this article, I have failed in my duty as your backyard vineyard tutor.

Remember that a virus cannot be removed from grapevines by any means. A cutting that is infected will produce a vine that is infected. There’s nothing you can do besides yanking the vine out and starting again with clean, certified nursery stock. Diseases caused by viruses that are not described here include rupsestis stem pitting and corky bark. As is the case with preventing all grapevine viruses, the key is to use clean (certified) materials when planting your vineyard.

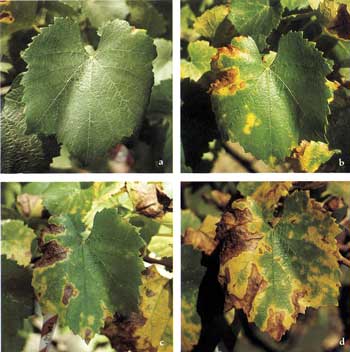

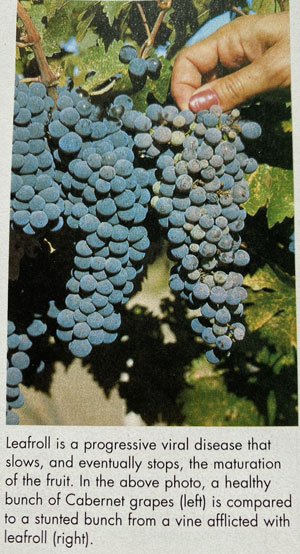

Leafroll: This is a viral disease that will result in reduced yield. The reduction in yield is not striking in the first few years that the virus causes the disease, but usually progresses until the vineyard is no longer producing a viable amount of grapes for wine. Some vineyards with leafroll are not replanted, and if the disease is not too severe, yields are reduced, but vines continue to produce fruit. Symptoms are usually visible on the leaves, and are more pronounced as water stress becomes apparent in late summer. Leaves that show rolled shape and become yellow or red are exhibiting the symptoms of leafroll virus, especially if there is green banding next to the veins of the leaf. Like most viral grapevine diseases, there is no known cure for leafroll. To reiterate an essential lesson in virus prevention, make sure to replant with certified stock.

Fanleaf degeneration: We should discuss fanleaf degeneration because it is not purely a nursery issue, and is spread by the dagger nematode, which is a species of roundworm that feeds and breeds in the roots of grapevines. Once a vineyard site has been infested with dagger nematodes, it will be a very difficult and expensive challenge to keep the pests out.

The nematode spreads the disease by munching on infected roots, prior to feeding on (and infecting) the “clean” roots. The key here is to recognize that the bug cannot spread a virus that doesn’t exist. With this in mind, it is clear that planting clean, certified rootstock will almost ensure that your vineyard will be free of this disease.

In very few instances, nematodes are able to spread fanleaf from one infected vineyard to a clean one, but this is certainly an exception, and a rare one at that. Once a vineyard site has been infected with both the nematode and the virus, it is almost impossible to ever replant without the good probability of subsequent infection. Allowing the ground to go fallow for 10 years has proven effective.

Symptoms of fanleaf virus include a disfiguring of the leaves. The “sinus” of the leaf becomes more “open” (where the leaf blade meets the petiole, there is usually a “v” shape, which is missing if infected), and the “teeth” on the leaf blade become sharper and more elongated.

In severe infections, the areas next to the veins on the leaf blade will become brightly banded with a creamy yellow color. You may also notice an increasing number of small “shot” berries on clusters, but by itself, this is not a clear indication of fanleaf, as most “shot berries” are caused by zinc deficiency or uneven fruit set.

Conclusion

The most important lesson to learn about grapevine diseases is that careful decision-making and monitoring is absolutely vital to keeping your grapevines healthy. Start by choosing a nursery with an excellent reputation for providing customers with certified virus-free grapevines.

Plant on land that has not been host to nematodes and diseases. Be careful with your practices and your pruning. Help the vine help itself with an appropriate trellis, balanced nutrition and canopy management that promotes a fruiting zone that is open to wind and some sun flecking. Treat your pruning wounds with a compound that will limit the spread of fungal pathogens, especially if pruning must be done in wet weather. Learn the warning signs of mildew, rot, fungal, insect and viral diseases and act quickly if you see a problem develop.