Q I made two barrels of Alexander Valley Cabernet Sauvignon this year, and the barrels are pretty old, so I don’t think I’ll get a lot of oak aroma or flavor out of them. I really don’t want to spend the $2,000 (!) to buy a new barrel and am wondering if you could recommend how I can get some good aging oak on the wine in a way that’s not cheap tasting but would be appropriate to do the grapes the credit they deserve. I got the fruit from a buddy who supplies local famous wineries and I’d like to do the wine justice . . . just not thousands of dollars worth, if you get my meaning.

William Schultz

Windsor, California

A Hey, I see you, I hear you, and I’m so here for you! The average price for a French oak barrel has really become very high in the last couple of years (decades?) and winemaking is an expensive enough undertaking without loading all of that up-front cost into it. A new French barrel can easily cost over $2,000 and, as far as the straight-up oaky aromas and flavors are concerned, only have about three- or four-years’ life in them before they become relatively neutral storage vessels. As an old friend of mine would wryly sniff, “A used barrel is merely medieval Tupperware.” I don’t agree with him 100% but it is indeed true that the hint of vanilla and that kiss of toasty spiciness we love in a well-made wine becomes increasingly difficult to attain as a barrel gets older. While even neutral barrels provide a quality-enhancing dynamic aging environment where tiny bits of oxygen are allowed ingress over time, the aroma and flavor compounds we associate with top-quality wines, especially Cabernet Sauvignon, require at least a small amount of newer, toasted oak.

So, what’s a conscientious but impecunious winemaker to do? You can easily level up by introducing some delicious new non-coopered oak into the equation. What do I mean by “non-coopered oak” you may ask? It’s a term I came up with years ago to describe well-sourced, carefully toasted oak that just didn’t happen to be bent and built into a barrel. Far from the sawdust and factory-floor sweepings of 20 years ago, the choice of “non-coopered oak” available to today’s winemaker is truly astounding. Just about every major cooper (barrel maker) I can think of is also offering a line (or five!) of wood from their company, which can be administered in something other than barrel form. From small particles the size of a grain of rice to yard-long staves that can be built into aging stacks in stainless steel tanks or concrete eggs, there are many application types to choose from. Any toast level you’d want in a barrel can be found, from untoasted practically white wood all the way up to the highest, coffee-toffee char. In short, if you can dream it for your wine, you can probably find it.

. . . the aroma and flavor compounds we associate with top-quality wines, especially Cabernet Sauvignon, require at least a small amount of newer, toasted oak.

If I sound like an oak-piece sales rep it’s because I really want to encourage all home winemakers to give the world of non-coopered oak a spin. Gone are the days when you’d have to “pick-your-own” from a mystery bin of barrel-reject pieces in the back of a home winemaking supply store. Here are a few of the ways you can introduce oak into your winemaking:

- Oak in the red fermenter: I know it’s a little unorthodox but I learned it while I was working for Randall Grahm at Bonny Doon Vineyard (well, he is known as the King of Unorthodox Winemaking, after all . . .) and I’ve been a big fan ever since. The heat and increasing alcohol level of a red fermentation is the ideal time to get a jump on oak extraction and integration, which is why I highly recommend fermenting on about 1–1.75 g/L of small-particle oak.

A good standard item is something like French Medium Toast “pumpable-size” (so called because it’s small enough to go through a pump and hose) but not so small that it’s like fine sawdust. The smaller the particle the faster the extraction, and you can get a lot out of wood this size in the 7–14 days of your average red wine fermentation. There’s no need to “remove” the oak later, you just press it off and settle with the rest of your grape solids. You can also put larger oak pieces into food-grade mesh sacks and then suspend them in your tote or macro-bin. You can then re-use the chips if you want because it’s possible that they won’t have finished extracting by the time the fermentation is complete. At the fermentation stage, oak can also serve as an antioxidant, a source of sacrificial tannins, and can even help support colored compounds. In my experience, light to medium oak toasts can also help reduce the perception of green and unripe characters if your Cabernet is leaning that way. - Oak in the barrel: It’s time to bring some new oak back to your barrel! Whether it’s “chips in a sock” (like a tea bag), a cut-wood spiral, chains of pieces hooked together and passed through the bunghole, or even an elaborate internal scaffold; there are so many ways to put new wood into your barrel. Coopers and oak-supply companies have come up with several inventive ways to get their product into our barrels. Do keep in mind, however, that some methods are easier than others. A metal infusion tube or nylon sock “tea bag” can be easier to remove than complicated, connected sticks. The many-pieced chains of wood sometimes get stuck into the barrel, making the barrel impossible to clean. At this point, you may just be better off doing the tea bag or sock. Some barrel companies offer a service where they remove the barrel head and actually build a scaffold of new wood inside (replacing the barrel head obviously). This way, your wine gets the double benefit of the aging dynamics of the barrel itself along with the new aroma and flavor compounds from the fresh oak.

- Oak Trials: Don’t forget, you can always do bench trials with oak chips. Though doing a bench trial of a large piece of stave wood is impossible, often the same company will sell the same wood (French, three-year aged) and toast level (say, Medium+ with half untoasted) in a chip or bean form so you should be able to get an approximate idea of what it might impart to your wine. It’s always good to have an idea of what such a substantial investment will impart on your wine.

Below is some information about barrel/oak/wood companies I’ve had some luck working with in the past few years. Please note, I do not have any endorsement agreements with anyone, nor is their mention here an indication of any kind of guarantee on my part. These are simply some of the companies I’ve dealt with in a positive way in my professional winemaking life in the last few years and I thought I’d pass on my experience to you. There are other products available in the hobby wine world, like Wine Stix, that I have not used.

Stavin (www.stavin.com): Stavin practically invented high-end, non-coopered oak in the United States and was a first mover in custom toasts and different flavor profiles back in the early 2000s. Their wood is carefully sourced in France, Hungary, or in the U.S. (depending on the origin of oak wanted) and then is either fire-toasted in a metal hoop just like a barrel would be or, in some of their newer lines, kiln-toasted. One of their specialties is a product called Barrel Head, which is a very light toast and is great if your Cabernet has any green or unripe character to it.

Their delivery format is either “granular” (good for fermentation at about 1.5 g/L) or “beans,” which are cute little cubes about the size of the end of my pointer finger. They are small enough to go nicely into a barrel sock type insertion but Stavin also sells perforated metal infusion tubes if you really want to give your barrel a good dose. Stavin also produces an interesting liquid oak additive called “Fire” that needs careful bench trialing to decide if it’s appropriate for your wine. Be careful, a little goes a long way and it’s expensive (but not as expensive as a new barrel!).

Radoux (www.tonnellerieradoux.com): A respected French barrel company, Radoux started working in the non-coopered business about ten years ago. Their Pronektar line offers powders, granules, segments, and staves. Their segments are about 2.5-in. square x 1⁄3-in. thick or 6-sq. cm x 1-cm thick providing an even toast while the staves are about the size and shape of a yardstick and come in mesh sacks or “fan arrays” held together by food-grade zip ties. These are great for hanging in porta-tanks or small fermentation vessels but don’t fit into a barrel. Because the pieces of wood are bigger than a chip or bean, they do take longer to extract. In my experience this is very top-notch oak well worth checking out.

Barrel Mill (www.thebarrelmill.com): This is an unassuming, under the radar company that supplies whiskey barrels and various flavors of oak (delivered in spiral form) for wine aging. I’ve found their spirals to be quick-extracting, in about two months or so, and the flavors and aromas of the oak are pretty well-integrated in that short amount of time. Their barrel-insert spirals are quite affordable, at fractions of dollars per gallon rather than tens or hundreds of dollars per gallon for a new or even once-used oak barrel. What’s pretty cool is that you don’t need to use the entire spiral all at once. In other words, if you want a lower oaking rate per gallon you could simply break off a piece of one and hang it in the barrel. Elegant, convenient, affordable, and tasty.

G3/Boise/Vivylis (www.g3enterprises.com): This is a large company that is supplying some innovative products to wine companies large and small. I’ve worked with some of their very quick-extracting chips, which they can provide in a wide range of flavors. These chips extract to give you some “good stuff” in as little as three weeks (though a full 8–10 weeks is preferred) and have less of a “chippy” fake taste than some other “chip-size” oak. Contact the company and request samples for big-bodied red wines. Their SC180XL and Phenesse Lush and Tradition chips do great with Pinot Noir. Cabernet might do better with something like their DC180 or other lines. You can do trials with small volumes before you decide what you’d like to use with your Cabernet (or other wines).

Long story short (and this is for all my readers, and not just our friend who wrote me this letter) — there is a whole new world of non-barrel oak out there that has been a professional wine industry “secret” for far too long. There are so many more sustainable and more environmentally friendly ways we can age our wine that doesn’t include the use of “medieval Tupperware” (making, transporting, filling, emptying, and cleaning barrels are a leading source of water and energy waste in the wine industry). As my mentor Randall Grahm used to say: “Winemaker, step away from the barrel.” What he usually meant was that we shouldn’t clobber our wines with unnecessary lashings of brand-new oak barrels. What he also meant, because we were living it daily in the cellar, was: “Winemaker, don’t be afraid to use oak that doesn’t come in barrel form.” I encourage you to expand your horizons in similar ways.

Q I need help in solving a riddle with a high titratable acidity (TA) and medium-high pH raspberry wine. I am aging This raspberry wine currently and the TA, post-fermentation is about 13.4 while the pH is 3.6. That seems pretty far out of line with what normal wine specs are and I’m not sure how to deal with it. Also of note, I added some calcium carbonate and the pH/TA balance didn’t react like I expected it would. What do you recommend for continuing treating/aging of this wine?

Here’s an outline of what I did (edited for length): Prior to fermentation, I added the calcium carbonate and after two hours racked into a fermentation bucket. I took a sample and measured the following specs: pH 3.54, TA 11.5, Brix 22.

It looked like the calcium carbonate had worked. I Started primary fermentation using Lalvin 71b and added yeast nutrient. After primary fermentation ended, I racked the wine off the lees into a 6-gallon (23-L) carboy: pH 3.6, TA 13.25 (??) how did it go up?

One week later I racked again: pH 3.6, TA 13.5. I proceeded to degas the wine and added ¼ tsp. of potassium metabisulfite powder and finally placed in a refrigerator to cold stabilize.

So how would The Wine Wizard proceed from here?

Jeff Davis

Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

A I really applaud you for keeping such detailed records and testing regularly. This really helps me when diagnosing issues and coming up with ways to help. I want to start off by saying that raspberries are a really high-acid fruit and that high titratable acidity won’t necessarily track with the pH like it does in wine from grapes.

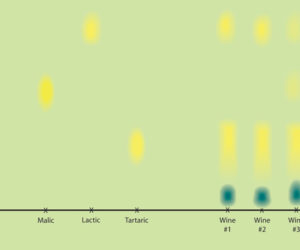

For background (and to add to the fun of fruit winemaking), there can also be a considerable swing in pH/acidity and Brix depending on raspberry cultivar and growing season. In a study of four varieties in the 1980s and 1990s, a TA swing between 1.5% to 2.64% was observed. Buffering capacities for fruits will be different and we can’t expect a raspberry wine to behave like a grape wine, especially when the inherent chemistries are so different. Grapes are high in tartaric and malic acids especially, with smaller amounts of citric and other acids. Raspberries don’t have tartaric or malic acids and are very high in citric and ascorbic acid. In short, deacidification rules and practices that we may be used to in grapes won’t necessarily apply when producing a raspberry wine.

Since there isn’t any tartaric acid, your cold stability seeding step (seeding with potassium bitartrate crystals) won’t draw out tartrates like you’d expect from a grape-based wine. I am curious, however, if chilling the wine down had any effect of moving the TA down. It would definitely be worth it for you to do another TA and pH measurement post-chilling to see where that moved your numbers. I’d be curious to see if freezing a small sample (and then measuring the pH and TA of the liquid on top of any precipitate) moved the TA and pH in a direction that you liked. But ultimately, “do you like the wine more?” is the real question.

Because pH determines microbial activity (and affects color), I’m not sure I would add any more carbonates (potassium bicarbonate or calcium carbonate) to deacidify any further. Does the wine taste OK to you, even if the numbers are “out of balance” when we’re talking about table wine? If the acid tastes unpleasant to you, one trick is to balance it out with some sweetness and then sterile filter your final product. Can you add some sugar and alcohol (like a non-harsh vodka or grappa) to make a sweet, boozy dessert wine? Sugar can cover up a lot of acid and help move a wine towards a more balanced state.

One of my favorite wines I ever had a hand in making was the famous Framboise dessert wine at Bonny Doon Vineyard. To make it (not that I can give away the exact formula), we took fresh raspberries and essentially macerated them in sugar syrup and neutral high-proof grape spirits. After a few weeks we pressed off and separated the solids from the liquids to create a sweet, higher-alcohol nectar. I know that’s not a traditional table wine and it’s very different than your product here, but I do think a lot could be achieved by adding some grape concentrate or sugar syrup and sterile filtering.