As an amateur winemaker, perhaps you know some old timers who age their wine in used spirit barrels that previously contained whiskey, gin, or rum rather than regular wine barrels. Spirit barrels are typically made in 5- to 30-gallon (19- to 114-L) sizes, which is often more suitable for the smaller volume winemaking of amateurs than the conventional 59- to 60-gallon (223- to 227-L) oak barrels used by commercial winemakers. Yet are used spirit barrels suitable aging vessels for wine? They certainly are less expensive than new oak barrels, but to what degree do used spirit barrels add desirable rather than undesirable aromas and flavors to the finished wine?

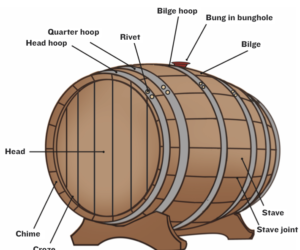

Let’s review a few facts about the similarities and differences between wine and spirit barrels. Wine barrels and spirit barrels are often both made from the same types of oak and with the same barrel design. Where they typically differ is in whether the inside oak surface is either slowly toasted or more quickly charred by fire during the final stages of construction. The insides of oak wine barrels are typically slowly fire heated to various light, medium, or heavy toast levels, infusing the wine that is later aged within it with such aromas and flavors as vanilla, coffee, and roasted nut. In contrast, the insides of oak spirit barrels are generally more quickly and intensely fire heated so that the wood is actually charred to one of four or five levels of intensity, imparting the liquor inside with such tastes and aromas as burnt toast, vanilla, and caramel, as well as tinting it with different shades of brown coloring.

Some commercial winemakers believe that there are tangible benefits to aging wine in spirit barrels. During the past ten years or so, a handful of commercial winemakers have dabbled in the aging of some of their red wines in oak barrels that previously held Kentucky Bourbon whiskey. The typical barrel aging duration varies from one month to eighteen months. For example, the Quattro Goombas Winery in Virginia produces a Bordeaux blend of Merlot, Petit Verdot, Cabernet Franc, and Cabernet Sauvignon that is aged for a few months in Bourbon barrels. Kentucky-based Wildside Winery’s Black Barrel Reserve is a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Chambourcin aged in Bourbon barrels for over one year. A much shorter duration of Bourbon-barrel aging is conducted at River Bend Winery in Kentucky, which gives its “Bourbon Barrel Red” 30 days of barrel treatment. Beyond the US, a group of Australian winemakers have aged Shiraz wine in Bourbon barrels for eighteen months, creating a “Southern Belle Shiraz.”

While there appears to be a foothold already established for spirit-barrel wine aging among commercial winemakers, I did not find much enthusiasm for this practice among amateur winemakers during my search of home winemaking sites on the Internet. In various online exchanges, more than a few amateur winemakers acknowledged awareness of spirit barrels being utilized in wine aging, but few actually endorsed this practice. Here is a sampling of these comments: “I wouldn’t ferment in one. . . It will become too overpowering on table wines, perhaps you can wash away some of the flavor/aroma with SO2-citric acid solution soak for few days.”

“To be frank, the wine is often awful (to me); red wine and whiskey are just a little too odd.”

“As it was a common practice among the ‘old timers’ in my area, I gave it a try one year (aging a red wine in a whisky barrel). As far as I am concerned, it ruined the wine, gave it some off flavors.”

The Bourbon-Barrel Experiment

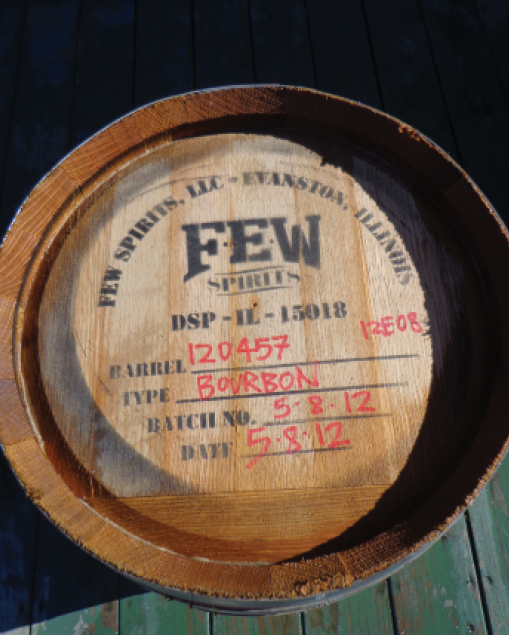

Based on this overview, it seemed that a wine experiment was warranted to identify the possible merits and potential perils of aging wine in spirit barrels. Fortunately, I am a member of the Wisconsin Vintners Association (WVA), consisting of more than 300 amateur winemakers in southeastern Wisconsin. Being in existence since 1970, the WVA has a number of wine-education activities, including a Wine Experiment Program that partially funded my proposed research. In this experiment, I tested the feasibility of using spirit barrels for wine aging by employing a previously used Bourbon whiskey barrel. For my “test” wine, I used a bit over 19 gallons (72 L) of blended red wine produced from two different Chilean-sourced commercial wine kits and fresh Chilean grapes obtained in late May 2013. This Chilean-sourced wine ended up being roughly about one-third Malbec, one-third Merlot, and one-third Cabernet Sauvignon. Three months later, following fermentation, racking, cold stabilizing, and sulfiting, all the wine was bulk aged in glass carboys for 39 days.

During this initial bulk-aging period, I purchased one 15-gallon (57-L) used oak Bourbon barrel and prepared a 3-gallon (11-L) glass carboy. To ready the Bourbon barrel for the wine, I rinsed it twice with 5 gallons (19 L) of cold water. Then a second racking of the wine deposited it into both the Bourbon barrel and the glass carboy, with a bit over a gallon (3.8 L) left in reserve to “top up” the barrel about every two weeks to replenish the wine lost due to micro-oxygenation.

After 40 days of barrel aging, a sampling of the Bourbon-barrel wine during a top up revealed a pleasant-looking dark, purple-red color and a rich, luxuriant flavor, with strong tannins and moderate acidity. There was no sign of a “browning” of the wine’s coloring due to the Bourbon barrel. At this still-young stage, it was a very nice-tasting wine. At the 100-day mark, this same wine had a hint of Bourbon aroma, a leathery, yet fresh-fruit taste, and moderate tannins.

Three hundred days after having deposited the wine into the two different aging vessels, I racked and sulfited the contents of both the barrel and the carboy into a series of glass carboys for a final three weeks of bulk aging prior to bottling. Finally, just before bottling, I constructed a third wine for the upcoming taste evaluations, namely, a 50/50 blend of the treatment and control condition wines. Therefore, the three final wines that made their way to bottling were the glass-carboy-aged wine, the Bourbon-barrel-aged wine, and the 50/50 blend of these two wines. Once bottled, these three wines were bottle aged for 50 days prior to being evaluated. At a monthly WVA meeting, 54 amateur winemakers participated in a blind tasting of the three wines. These tabulated wine evaluations were the dependent variables in this experiment. Prior to the tasting, the wine experiment was thoroughly described to everyone in attendance, and thus, all participants were aware of the differences in the way these three wines were produced. Yet because this was a blind tasting, during the evaluation process the identity of the wines was not revealed. Due to the logistical challenges of randomizing the tasting order of the three wines among all participants, I chose a fixed order, with the glass-carboy wine evaluated first, followed by the Bourbon-barrel wine, and then the 50/50 blend.

The wines were evaluated using the WVA wine judging form, which is adapted from the University of California-Davis 20-point quality range. Points are allotted for appearance (0-3 points), aroma and bouquet (0-6 points), taste and texture (0-6 points), aftertaste (0-3 points), and overall impression (0-2 points). All evaluators were given a small pour of each wine in the above-described order, but were also offered subsequent pours of all three wines if desired. After completing their evaluations, members ranked the three wines in the order of their perceived quality. All participating members were asked to indicate whether or not they were dry red winemakers and also whether they had judged dry red wines in past annual association wine judging competitions and/or state fair wine judging competitions.

Wine Evaluation Results

The results are broken down into three judging subsets. First, the results of all 54 participants are described, followed by the smaller subset of participants (30 members) who are red winemakers, and then the evaluations of five members who previously judged red wines in organized wine judging competitions.

Evaluations From All Participants

Overall, the two wines that contained Bourbon-barrel-aged wine were clearly preferred over the wine that was bulk-aged in the glass carboy. Among all evaluators, 42 percent ranked the 50/50 blended wine as their favorite, 39 percent ranked the 100 percent Bourbon-barrel-aged wine as their favorite, and only 19 percent ranked the glass-carboy-aged wine as their favorite. The least preferred wine was the glass-carboy-aged wine (76 percent ranked it third). In contrast, only nine percent of the evaluators ranked the Bourbon-barrel wine as their least preferred, and only 15 percent ranked the 50/50 blend as their least preferred. Tallying the average score of these three wines using the association’s 20-point evaluation scale, the 50/50 blend had an average score of 14.9 (standard deviation = 2.3), the Bourbon-barrel-aged wine had an average score of 14.8 (standard deviation = 2.4), and the glass carboy-aged wine had an average score of 13.2 (standard deviation = 1.6). Using the WVA’s wine-judging criteria for first-place, second-place, third-place, and no-award categories, the two wines that contained Bourbon-barrel aging fit into the second-place award category. The glass carboy-aged wine fell into the third-place award slot.

Evaluations From Red Winemakers

When the evaluations of the red winemakers (56 percent of the total evaluators) were separated out for analysis, a clearer wine preference emerged. Fifty-four percent of the red wine- makers most preferred the 50/50 wine blend, while 31 percent most preferred the 100% Bourbon-barrel-aged wine. Only 15 percent of the red winemakers chose the glass-carboy-aged wine as their most preferred. As with the larger sample, the least preferred wine among the red winemakers was the glass-carboy-aged wine (78 percent), with the other two wines equally sharing the percent of third-place rankings (11 percent). Again, tallying the red winemakers’ average scores for these three wines using the association’s 20-point evaluation scale, the average score of the Bourbon-barrel-aged wine was virtually the same as in the larger sample (Mean score = 14.9, standard deviation = 2.1), as was the glass carboy-aged wine’s average score (Mean score = 13.0, standard deviation = 1.7). Red winemakers’ average score for the 50/50 blend was a half-point higher than the total sample of wine evaluators (Mean score = 15.4, standard deviation = 2.1). Based on the red winemakers’ average scores for the three wines, the award categories were unchanged from the total sample of wine evaluators.

Evaluations From Red Wine Judges

There were four WVA members among those in attendance who had past experience as judges of dry red wines at organized wine competitions. In addition, one of our members, Piero Spada, is a graduate of a well-respected viticulture and enology program and is a professional vineyard and winery consultant, so his evaluations were tallied with those of the four experienced red-wine judges. Any surprises? Not really. The 50/50 blended wine was the most preferred among four of these five evaluators and all five ranked the Bourbon-barrel-aged wine as their second preferred wine.

In extended comments, Spada remarked that the carboy-aged wine had a predominant fruity aroma and bouquet, with a silky, smooth-finish aftertaste, yet it lacked oak tannin structure. In contrast, he evaluated the 50/50 blend as having prominent oak aromatics, with fruit bouquet still present; the taste was dry and medium bodied, with pleasant tannins and an oak-tannin aftertaste that lingered on the palate and was silkier than the Bourbon-barrel-aged wine. Overall, Spada rated the 50/50 blend as having good integration and balance between the fruit and the oak.

Regarding the Bourbon-barrel-aged wine, Spada judged it to have predominant woody aromatic notes that was somewhat lacking in fruit. He noted that the charred Bourbon barrel lent a hint of vanilla and coconut to the wine’s aroma. He judged the taste of this wine as dry and medium-bodied, with proper acidity, but he also thought it was excessively harsh due to the rough tannins from the charred barrel that buried the wine’s fruit taste. He further stated that the most pronounced aspect of this wine’s aftertaste was lingering oak tannins. Overall, Spada judged the Bourbon-barrel-aged wine was “acceptable,” but thought its heavy oak aroma and taste overpowered the wine’s fruit. Instead of serving as a stand-alone wine, he thought this wine had exceptional value as a blending component.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The purpose of this wine experiment was not to determine whether wine aged in a spirit barrel yielded better results than wine aged in a traditional wine barrel, but rather, whether such wine had benefits over wine aged in an inert vessel, namely, a glass carboy. Due to the lack of available evidence on the benefits or decrements in such barrel aging, the current study fills an important gap in our knowledge base. Yet what is it that we can glean from the results here?

First, it is safe to conclude that aging red wine in a Bourbon barrel has some definite benefits that cannot be achieved through simple glass carboy aging. The current findings indicate that a Bourbon barrel has the ability to infuse red wine with pleasing oak aromatics and tannins, while simultaneously maintaining the wine’s natural fruit bouquet. Yet a second conclusion to draw from this experiment is that the duration of time that wine should age in a Bourbon barrel in order to achieve optimum balance between oak tannins and fruit flavors is perhaps shorter rather than longer. This second conclusion is reinforced by the individual comments of Spada, who detected some harshness in the wine aged for 300 days in the Bourbon barrel but not in the 50/50 blend.

Although many of the evaluators rated the 300-day Bourbon-barrel-aged wine as their favorite, the majority of the total participant evaluators, the majority of the red winemakers, and the much smaller subset of the experienced red wine judges found the 50/50 blend to be the most pleasing wine, meaning that it had the best integration and balance between the fruit and the oak.

In conclusion, based on the results reported here, I think it is safe to state that, for many amateur winemakers, Bourbon whiskey barrels provide a relatively inexpensive vessel in which to age wine.